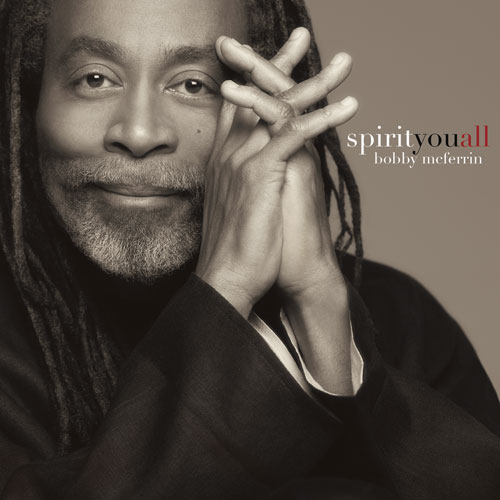

Every once in a while, an artist comes along who is so phenomenally talented that it almost seems unfair to every other artist. For me, one such person is Bobby McFerrin. I remember listening to “Peace,” sung by McFerrin and written by the incomparable Horace Silver, and being moved beyond words by the beauty of the song. And now, some 30 years later, after reading the news about wars, kidnapped schoolgirls, planes being shot down and all the other ills that face our world, when I listen to that same song, it still brings a sense of calm to my spirit. So, it’s no surprise to me that McFerrin’s latest endeavor is aptly titled, spirityouall.

I have often wondered who or what could have influenced McFerrin to have the ability to sing and perform in such a manner that is so universal, and when he was asked that very question, in an interview with iRock Jazz, he stated, “I was lucky to grow up in a house filled with music. Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, The Beatles, Fred Astaire, Louis Armstrong, Etta Jones. Top 40 radio. Anything and everything.” Therefore, it makes sense to me that his music should be able to speak to the spirits of anyone and everyone who listens.

As Bobby McFerrin continued his conversation with iRock Jazz, he discussed the spirityouall project, his early beginnings, the affect “Don’t Worry Be Happy,” had on his career, as well as the key to his longevity in the business. His interview informs, but it also explains how all of his musical influences and his upbringing allow him to touch the spirit in us all.

iRJ: Tell us about spirityouall.

BM:The spirityouall project took shape in an interesting way. For years, decades really, I had a fantasy about making an album that showed the world how important blues/rock/folk music was to me. I thought everyone could hear that I had classical and jazz and world music influences, but I couldn’t understand why nobody could tell I had also been so deeply shaped by the American bands I heard growing up. I had dreams of recording with Eric Clapton or James Taylor. Separately, I also talked on and off about making a tribute to my dad, maybe recording some of the spirituals he sang. When I was very little I’d overheard him working on those songs with the legendary Hall Johnson, whose grandmother was a slave. I knew I could never sing the songs the way he sang them; he already did that better than I ever could. So I had to find my own perspective, and again the idea kicked around forever and didn’t really go anywhere. Then all of sudden the two ideas merged and everything fell into place. That’s how spirityouall was born.

iRJ: At what age did you begin singing?

iRJ: At what age did you begin singing?

BM: I can’t remember a time when I didn’t sing, and my very first memory is of standing up in my crib and singing through the wall; my sister was on the other side in her room, singing back to me. But throughout my childhood and well into adulthood, I thought I was the instrumentalist in a family of singers. I studied the clarinet very seriously, then switched to the piano, and my early years as a working musician — from age 14 until age 27 – were as a pianist. Then one day I was walking home from playing for a dance class, and suddenly I understood I’d been a singer all along.

iRJ: How did you develop your gift for polyphony, and when did you realize you had this talent?

BM: Wait, what? I have a gift for polyphony? I’ve never thought about whether that’s true, and maybe it is. What I do know if that because I was a pianist first I think and hear in more than one line, maybe more than a lot of singers. And a couple of my most memorable early listening experiences pushed me in that direction – singing Bach in the church choir, listening to the Miles Davis electric band, hearing African choral music in the score to the film Zulu.

iRJ: Before the release of your first solo project, you didn’t listen to other artists while developing your own unique style. Why did you choose to do this?

BM: Singing is so personal. I think it’s easy for singers to imitate the style or tone color or pronunciation of another singer they really admire. So I always suggest that singers listen more to instrumentalists than other singers. I think it’s great to draw inspiration from other art forms too. I think I was really inspired by Fred Astaire, not just as a singer but as a dancer. Such a light touch, so much joy.

iRJ: Do you listen to other artists now, and if so, who?

BM: I’ve really been enjoying traveling with a band again, we’re performing together every night on tour. So Gil Goldstein, David Mansfield, Armand Hirsch, Jeff Carney, Louis Cato, and Madison McFerrin are the artists I’m listening to this month!

iRJ: “Don’t Worry Be Happy” was a huge hit. Were you surprised by its success, and what impact did “Don’t Worry Be Happy” have on your musical career?

BM: Nobody was more surprised than I was when that song became a hit. But it gave me the chance to reach a lot of people, people who might never have listened to an improvising singer. I’m grateful for that, and I’m grateful for the opportunities that came my way. Before the song became a phenomenon I had a really clear idea of what I wanted to do as a musician, as a singer. The opportunities that came after made me consider and clarify. Ultimately I turned a lot of things down, and I stayed pretty true to my original ideas: performing solo, forming Voicestra, getting audiences to sing and play, learning more and more to trust the moment.

iRJ: So, why the switch from a solo artist to conducting orchestras?

BM: I didn’t switch! I’m a singer first and foremost. Conducting — well, I remember being a toddler and conducting Beethoven symphonies as played by our living room stereo. So, when I turned 40, I had some friends at the San Francisco Symphony, and I asked if I could conduct something on my birthday. When they said yes, I took some lessons, I didn’t want to make a fool of myself or let them down. I was surprised and happy when I got a bunch of invitations to conduct after that, and I’ve loved those experiences. But I don’t conduct very often anymore. When I do, I try to approach it the same way I sing. I try to sing with my hands.

iRJ: Your touring schedule is insane. How often are you out on the road, and how do you adjust that rigorous schedule with your family life?

iRJ: Your touring schedule is insane. How often are you out on the road, and how do you adjust that rigorous schedule with your family life?

BM: I do about 100 shows a year. I wish there were a magical way I could do concerts all over the world and still sleep in my own bed every night.

iRJ: Since you spend so much time on the road, would you encourage your children to pursue the same career path, or are your children already in the business?

BM: My children are very talented. Madison just graduated from college and is touring with the band, Jevon is on Broadway in the cast of Motown: The Musical. Taylor just released his first album to great reviews, and they are all just wonderful people. I love spending time with them. I’m a very proud papa.

iRJ: Did you have any mentors? Do you mentor anyone now?

BM: Too many too list in both categories. I work with some younger musicians, and I teach a workshop every summer for improvising singers, and I’m always amazed when people come up to me at concerts and say that a particular song or record was important in helping them find their own creativity. But then I remember how it was for me — some things I listened to just changed me forever, changed who I was as a person and an artist.

iRJ: What is the key to your longevity?

BM: Music, prayer, and play!

Bobby McFerrin was once quoted as saying, “If I can bring joy into the world, if I can get people to stop thinking about their pain for a moment, or the fact the tomorrow morning they’re going to get up and tell their boss off… then I’ll be successful.” For him, that may indeed be the meaning of success. But for those who have experienced joy, who have forgotten their pain, and who have indeed gotten up the next morning to give their boss a well-deserved telling off, all because of one of his songs or records, McFerrin’s quote about his music is more than just the definition of success. For them, his music is spirityouall.

Words by Geveryl Robinson