Jazz was the first music Randy Brecker heard in his home, and says “bebop is at the root of everything.” While growing up in Philadelphia, he was exposed to a plethora of musical styles. Brecker relocated to New York in 1966, during what he calls “an exciting time!” He was greatly inspired by The Free Spirits; a jazz-rock band. He was involved in the jazz-studio scene, and the jazz-rock scene, which later became fusion. Brecker was an original member of the band Blood, Sweat & Tears in 1967, but he left to join the Horace Silver Quintet. In 1970, Brecker and his brother, Mike (a saxophonist) formed a group called Dreams, and became the house band at The Village Gate.

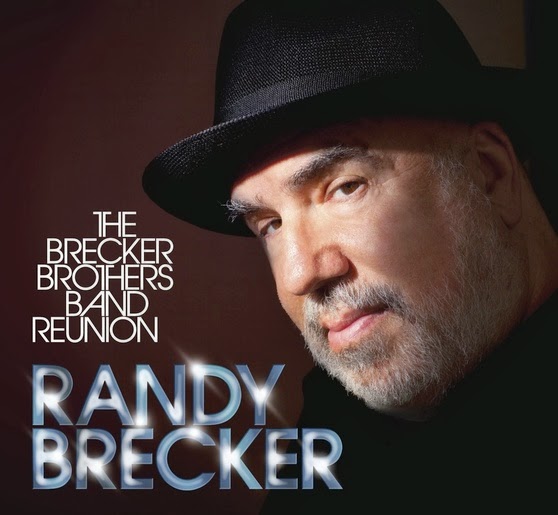

Brecker and his brother formed The Brecker Brothers in 1975, and were signed to Arista Records. They were in constant demand as session players. In 1994, they won two Grammy Awards for their album Out of the Loop. Brecker has won a total of five Grammy Awards, and has worked with countless artists, ranging from Art Blakey to James Taylor. Brecker sat down with an iRock Jazz writer to tell us about his music, and spending over four decades in the industry.

Brecker and his brother formed The Brecker Brothers in 1975, and were signed to Arista Records. They were in constant demand as session players. In 1994, they won two Grammy Awards for their album Out of the Loop. Brecker has won a total of five Grammy Awards, and has worked with countless artists, ranging from Art Blakey to James Taylor. Brecker sat down with an iRock Jazz writer to tell us about his music, and spending over four decades in the industry.

iRJ: Why do you think jazz has not been developed as well as hip-hop, from an entrepreneurial standpoint?

RB: That’s a good question. hip-hop guys, and rappers usually have really astute businessmen behind them. They don’t have to spend time [practicing] on their instruments; maybe that’s part of it. They write lyrics, and it’s an art within itself. Most jazz musicians didn’t have that kind of backing (as far as management). They were intent on learning how to play, and practice ten or twelve hours a day. A lot of the masters were great musicians, but they weren’t great businessmen; that came later. With younger players, it’s different. Robert Glasper is a perfect example.

iRJ: Jazz is called “black classical music” and jazz musicians tried to protect the music instead of promoting it. Do you think this is true?

RB: I think at one point it was true. In the sixties, a lot of African-American musicians wanted to keep the music to themselves; rightfully so. They felt they were being ripped off by management; record companies; and other people, who also wanted to play it. I think that sentiment has changed throughout the years. Jazz, in particular, has become so globalized, and there are such great players all over the world, and that’s a good thing.

Things have changed quite a bit since the sixties. I think of Max Roach, and the book by Art Taylor; where he interviewed a lot of musicians. Again, that was the sentiment of the sixties. And people were trying to break free in the African-American community; and did — to an extent. Of course, we all still working on it, but I think the jazz world had a part in [helping] African Americans to find their place.

iRJ: If you look at Parliament Funkadelic diagnostically, would you say it was about the music; about hype; or about word-of-mouth movement, which just caught onto a generation of that music revolution?

iRJ: If you look at Parliament Funkadelic diagnostically, would you say it was about the music; about hype; or about word-of-mouth movement, which just caught onto a generation of that music revolution?

RB: It’s a little of all three things. They were billed as The Funkadelics. And we first heard them at a huge outdoor festival in Chicago in 1970; we were on the same bill. Parliament Funkadelic played after us, and the first thing that caught your eye, before the music began, was the outlandish costumes. We’d never seen that before, but that was a big part of their success. When you listen a little deeply, and realize how funky they were, it was just an amazing combination of music and showmanship. With “word of mouth,” they became popular pretty quickly. You have to mention James Brown in the same breath, because so many of the players in Funkadelic came out of James Brown’s style, and that whole conception.

iRJ: How difficult is it playing music for so many genres?

RB: For some musicians, it’s harder [to do] than [it is for] others. Mike and I, once again having come up with R&B in Philadelphia; working in trios, it was always an easy shift. We grew up seeing Jimmy Heath, Benny Golson, Lee Morgan, and all of the great jazz musicians from Philadelphia. They always kind of co-existed. And a lot of jazz musicians took R&B gigs so it was always an easy shift for us; mostly rhythmically to play in other circumstances. The vocabulary we used was the same, but the rhythmic influences, and inflections, were different.

I try to do, consciously, what I started doing in the early seventies for the band; which was to take a lot of the jazz harmonies and adapt them to a more rhythmic funk concept. And bring more harmonic inflection, and sophistication, to the music. So, the idea was to take rhythmic and sonic elements, from rock and R&B, and mix them with the sophisticated jazz harmonies.

iRJ: What direction is music going in today?

RB: I use a phrase that Jack DeJohnette coined, “It has gone multidirectional.” All music has become so globalized that you can’t really point to a direction. American music is heavily influenced by music from all over the world. You can barely look to America; only for new sights and sounds. It has become a globalized community, with all the social networking, where you can just hear and see anything. So, it’s going in a million different directions at once. The process today is an open palette, so to speak.

The trick is to find your own voice. I think the good musicians always go back through the [music] history, and utilize everything they can. Dr Dre, he comes to mind, came up through the Quincy Jones’ school of production, and has a respect for the history of the music. The way a lot of it seems to be going is the people who create the “so-called music” are not musicians, and you can notice that [difference]. I, once again, state that jazz is really at the core of a lot of stuff. All of the Motown guys were jazz musicians. The Gamble and Huff guys were jazz musicians. I knew all those guys. Quincy Jones is an example. The well-produced records had that common element.

iRJ: What’s your take on the ongoing debate that jazz should be “listened to, and not danced to”?

iRJ: What’s your take on the ongoing debate that jazz should be “listened to, and not danced to”?

RB: I don’t dance too much anymore, but I definitely enjoy the rhythmic aspect of jazz. I constantly go back and listen to Count Basie, and Duke Ellington, and all of the great swing bands. That element appeals very deeply to me. I like rhythmic music. I enjoy [listening to the] more “free” type of music. But I think, at the core of my being, because I came up with that [style], I still enjoy [hearing] the rhythmic aspect. So, it’s fine with me if people want to dance.

iRJ: Jazz musicians have been known for their sharp image, usually wearing suits and ties. But, today their dress style has become more casual. What are your thoughts on this?

RB: I was on Youtube, and I was watching an old Lambert Hendricks and Ross clip; and the cats were wearing tuxedos. I hate wearing suits and tuxedos. I came up wearing more casual clothes, but guys do look great when they dress up. Now that I’m older, I enjoy doing it myself. It lends a nice, dignified “air” to the proceedings. Modern Jazz Quartet comes to mind; back when Miles was wearing suits. And I think it looks pretty good. Of course, Wynton brought [doing] that back in style. But, on the other side of the coin, it depends on the music.

iRJ: As a non-African-American person, how were you welcomed into the music community?

RB: I had some good experiences; some great experiences; and some not so great ones. Coming up in Philadelphia, I was adopted by the black community, and it’s something I’ll always treasure. They took me in, and I had a great opportunity to learn, first hand, from really great musicians.

I played at a lot of African-American dances; I was the only white guy in the band. I had an affinity to play in that style, but the guys in Philly were just great to me. Occasionally, we ran into people who thought we shouldn’t be there; especially back in the sixties when black music should’ve been played only by black people. I think the world, amongst musicians, now is color blind. But, in the sixties, it was a good thing that African-American musicians stood up for their music. It was a part of the process; an important part of the process. People like Max Roach, Charlie Mingus and others were very verbal about the discrimination they were feeling.

iRJ: Tell me about your current project.

RB: I was supposed to do a solo-week at the Blue Note Club in New York. And they had a list of people they wanted me to call to put a band together. After I put the band together, I realized that everyone had played in various editions of The Brecker Brothers. I mentioned it to the people at the Blue Note and next thing you know they are calling it a Brecker Brothers reunion. I had written new music with the intention of doing a solo record.

The Brecker Brother thing crept into the picture and the week was sold out. People really liked hearing the new tunes. We did a tribute to my brother, played a couple of his tunes and talked about him. My wife, coincidentally, is a wonderful saxophonist, and I don’t think I would have done this without her. If I had to call up another saxophonist, I wasn’t related to. So, it kept the franchise in the family. She has her own voice.

The Brecker Brother thing crept into the picture and the week was sold out. People really liked hearing the new tunes. We did a tribute to my brother, played a couple of his tunes and talked about him. My wife, coincidentally, is a wonderful saxophonist, and I don’t think I would have done this without her. If I had to call up another saxophonist, I wasn’t related to. So, it kept the franchise in the family. She has her own voice.

She wrote a tune and brought a young gentleman into the picture, named Oli Rockberger, who is a wonderful singer, and composer, in his own right. Of course, we miss Mike, but this band is my legacy. It’s the thing I feel closest to. It’s proven to be a really nice thing. I’m not going to do this one hundred percent of the time. But, for the next couple of years, it’s going to occupy a decent amount of time. The new record is full of new technology, and new tunes; in the style, but it has morphed into something a little different.

Words by Shonna Hillard