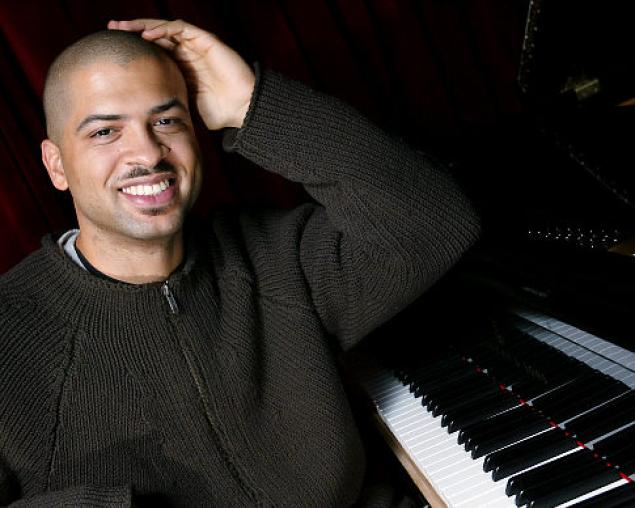

Jason Moran is a Houston, Texas-born pianist and composer. His eclectic styling has led to a successful run of over fifteen years, as both sideman and band leader. In this time, Moran has received considerable praise for his fluid play, which encompasses various styles, blending them into one definably distinctive voice. Beyond that, Moran is musical advisor for jazz at the historic Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

This is but a snapshot of Jason Moran’s life. Significant in its own right, there is a much greater abstraction that defines his current position. At 38 years of age, Moran is not quite an elder statesman of jazz nor is he a part of its crop of up-and-coming musicians. He is a firmly established artist in transition, a contradiction that only comes with age.

Recently, iRock Jazz sat down with Jason Moran to talk about his past, present, and the inevitably of change over time.

iRJ: You went to the same high school [Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts] as Derrick Hodge and Robert Glasper in Houston. What was so unique about that school?

JM: There are a lot of reasons. I would say it allowed people who were pretty weird to be weird with each other [laughs]. People who – in their teenage years have found a serious calling and would devote the next three or four years, or however many years they spent at that high school, really studying that craft. That’s pretty rare for a child to kind of figure that out. And then, I mean, really if I talk about anything about the school, it’s about the peers, the other students. They would egg you on. Everybody was trying to play. And if you didn’t know how to play, then you would get inspired by looking at your peers. Like, ‘Aw man, they figured that out? Ok. Well I need to figure that out too’. And so you had a lot of ways of playing off of one another just being around people who are also as passionate as you are. And the teachers, they were phenomenal because they understood what the passions of the students were and they never wanted to get in the way. They only wanted to enable you to get further in your career as an artist rather than shoot you down.

iRJ: Were there any tell-tale signs that you all were special and that you stood out artistically?

iRJ: Were there any tell-tale signs that you all were special and that you stood out artistically?

JM: I don’t think so. We were all just trying to play. We wanted to play with each other. Every once in a while we’d get kind of a glance at what the national scope of high school musicians looked like. Our rival high school in Texas was up in Dallas. It’s called Booker T. Washington [High School for the Performing and Visual Arts]. Roy Hargrove and Erykah Badu and Norah Jones, they all went to that high school. So there was kind of like this bit of a rivalry with that school, but otherwise we were just trying to play. And we were trying to play with people who were in the scene already, like the professionals that were in the scene in Houston. It wasn’t that we thought that we were really good, but we wanted to be able to play and go to work to be hired for gigs. It wasn’t until I came up to New York and I went to Manhattan School of Music that I realized how special the school was. Because I heard these drummers, which I thought, ‘Ok, anybody that’s coming to college clearly they’re gonna be playing on a whole nother level’, but that wasn’t the case [laughs], at all. These drummers up here sound only okay compared to the drummers I had been playing with in Houston. There was Chris Dave, who is older than me or Eric Harland, who was a year behind me and then all these people coming up – Jamar Williams and Kendrick Scott and just a whole bunch of drummers. So it wasn’t until I left home and I got up to New York that I started to kind of get a course of where people were that were in our age group. But then, you know, for me it was never about comparing myself to the person in my age group as much as it was comparing myself to McCoy Tyner [laughs]. Compare yourself to the best, not the guy nearby. The best in your field – that’s who you’re up against.

iRJ: While you were in college, how did you hone your craft?

JM: I was pretty reclusive, so I didn’t go to jam sessions. I didn’t like the jam session scene. I didn’t feel I was ready for it. I felt I had a lot of practicing to do. I was studying with Jaki Bayard and he gave me a lot of work. I spent most of my time either practicing, going to museums or listening to music and playing video games. That was the bulk of what I was into and the occasional girlfriends [laughs]. But that was my life. I wasn’t so into trying to go and play. The turning point might have been in my senior year of school and Eric Harland recommended me to play with Greg Osby. He hired me for a European tour without ever hearing me play a note. And that kind of changed everything or it started the course.

iRJ: What doors opened after playing with Greg Osby?

iRJ: What doors opened after playing with Greg Osby?

JM: Well, he was already signed to Blue Note Records, so I recorded a couple records with him and soon after Blue Note offered me my record deal. That may have been the most significant one to transpire. Also, Greg introduced me to my other teachers; Richard Abrams and Andrew Hill. So I began studying with them as well. It was just kind of like solidifying this base for me. In this base were Steve Coleman and Greg and Cassandra Wilson – all these people who kind of pivoted between different spaces within the jazz spectrum or improvisation spectrum. And they let a lot of the contemporary sounds into their music as well. You would hear influences of James Brown in Steve Copeland’s music or you’d hear hip-hop influences in Greg Osby’s music or contemporary blues in Cassandra Wilson’s music. They were all pretty transparent as artists. So being in that scene when I was in my early and middle 20s, that kind of helped get a real glance at what the creative music scene was about. Those kinds of things, I cherished.

iRJ: You’re now in that mid to late 30s age group where you’re not one of the young artists, but far from old. How do you define that gray area?

JM: I’m 38 now. So I’ve entered that space pretty recently. I had these ideas about what I was supposed to do with my 20s. I was really supposed to go out into the forest and just pull in as much as I could and then in my 30s I would just put a lot of that to action. I think in recent years, what I’ve been asked to do is not only be a player but also be a conceptualizer or a curator or a spokesperson for the music. That only happens with age. They don’t really ask you to be a spokesperson at 21. At this age now, when people as dear to the music scene as a Mulgrew Miller pass on, it becomes the comparative of this mid-generation to figure out how to talk about the music and how to share it in an interesting way with more audiences and make sure that you teach other upcoming musicians that there’s a way to do this too. Working at the Kennedy Center has been a very big shift in my career. Also working with the San Francisco Jazz Center has also been a big shift. People are looking at me now as more than just a pianist and a composer.

iRJ: You are now working with Theaster Gates. Tell us a little bit about that project.

JM: It’s a commission from the Chicago Symphony Center. James Fahey over there put together a series of concerts around the theme of speak truth to power. I thought this would be a way for Theaster and I to come together and kind of have an artistic discussion through our forms about the beautiful prospect that the city has created for other people of all kind of disciplines. If I think specifically, for my history, from the blues piano tradition, what the blues represents, what the south represents up north in Chicago, all that is good. But on the other side is kind of terrible. How do we improve these things within the human condition? What is the relationship that Chicago has to the rest of the world – not only Chicago to itself or Chicago to the media, but Chicago to Pakistan or Chicago to Australia? And so Theaster and I are working on a four or five movement piece around this subject of truth and power. That’s what we’re working on. It won’t premiere until June or late May of 2014. So we’re still in the process of making all of this.

iRJ: Where does your music fit into the world today?

JM: A theme that I keep revisiting over and over again is how does jazz relate to the world? With the Fats Waller Party it’s kind of this relationship with how audiences listen to music and if they want they should be able to dance to the music…again, as jazz was once dance music. I keep coming back to this. How does it relate? Does it relate just the jazz audience who comes to a jazz club? Does it relate just to a festival audience who comes to a festival and knows that it’s going to be a good party and they can meet up with their friends? How else does it translate? That’s where I’ve been for the past couple of years. It’s a long process. I keep trying to toy with this idea over and over again. And generally I enjoy having collaborators, because they allow lots of different influences into the presentation of the music that I think can benefit the music. I’m still a pianist first but I also want to make sure that I just don’t think about the piano, but that I think about thematic structures or dramatic structures of an evening that might pull an audience in deeper.

iRJ: What else are you working on now?

iRJ: What else are you working on now?

JM: I’m finishing up this Fats Waller recording that I’m doing for Blue Note. And I’m working with Meshell Ndegeocello, great bassist and singer. And so we’re almost finished with that. That’s a big one for me. We did some of the Fats Waller stuff at Symphony Center last year. And actually it’ll come to the Chicago jazz festival later this summer. So that’s what I’m working on right now. At the same time I’m working on the commission for the Chicago Symphony Center. I’m working on another classical commission for Imani Winds, this great chamber music women’s quintet that also consistently works with Wayne Shorter’s quartet. I’ve written one piece for them before and they commissioned another one for next year. But the biggest thing that I’m working on is really trying to raise my twin boys to be upstanding gentlemen later in their life. That’s the biggest work of art [laughs].

The man we know – an effective composer, a captivating musician – will remain. That is a fact. However, Jason Moran is in the process of redefining the space within which he works and in that we are being reintroduced to someone whose potential is endless in scope. It’s not an absolute change, but instead a case study in evolution. Only time will tell what Moran has in store for the future. Whatever it is, expect it to be nothing short of memorable.

By Paul Pennington