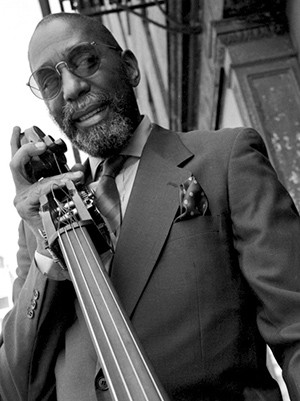

We love legends, don’t we? Not only do they use their talents to break barriers and achieve levels of greatness that few have seen, but they also use those very talents to lead a new generation to that same level of excellence and beyond. Master bassist, composer, leader, doctor and Professor Ron Carter has set an impressive standard for jazz bassists.

After a brilliant stint as part of the second illustrious Miles Davis Quartet, Carter has gone on to appear on over 2,000 recordings, making him the most recorded bass player in history. He has taught music at a number of universities, been awarded two honorary doctorate degrees, was given the title of Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Minister of Culture, and he currently sits on the Advisory Committee of the Board of Directors of The Jazz Foundation of America.

Carter is quoted as saying, “I think that the bassist is the quarterback in any group, and he must find a sound that he is willing to be responsible for.” And with him as the quarterback, all the new jazz players know they are on a winning team. In this special interview with iRockJazz, Ron Carter shares with us his thoughts on today’s musical landscape and gives us a “behind the scenes” peek into what it was like playing with the iconic Miles Davis Quartet.

iRJ: You didn’t begin your musical training on the bass. Tell us about how you came upon playing the bass and what challenges you faced as a musician.

RC: I switched to bass when I was in high school. I was about 18. It was 1954 I believe. I started playing cello when I was 10 years old, and I switched to bass because I thought that I wasn’t given the opportunities that the white cellists were given. Then I realized that at the age of 18 years old that there wasn’t a bass player, and they had to hire me even though I was an African American playing this instrument. What challenges were there? Well, the challenges still exist. If you look at any of the photographs of any of the orchestras these days, and look at all of these African American bass players who are graduating from all of these major universities, you find out that the proportion of African American players in orchestras has not changed dramatically in the past 50 years. So today they are facing the same issues, whether they say it out loud, that I did 50 years ago.

RC: I switched to bass when I was in high school. I was about 18. It was 1954 I believe. I started playing cello when I was 10 years old, and I switched to bass because I thought that I wasn’t given the opportunities that the white cellists were given. Then I realized that at the age of 18 years old that there wasn’t a bass player, and they had to hire me even though I was an African American playing this instrument. What challenges were there? Well, the challenges still exist. If you look at any of the photographs of any of the orchestras these days, and look at all of these African American bass players who are graduating from all of these major universities, you find out that the proportion of African American players in orchestras has not changed dramatically in the past 50 years. So today they are facing the same issues, whether they say it out loud, that I did 50 years ago.

iRJ: Why do you think there hasn’t been a dramatic change over the years?

RC: You’re asking me to answer for those people, and I really can’t do that.

iRJ: Fair enough. Can you tell us about some of the life lessons or musical lessons you learned from some of the great musicians you played with early on in your career?

RC: Well, there were too many to numerate right now; but I can give you three or four of them that come to mind most immediately. One of the focuses was being honest with your fellow musicians as you were playing with them on the bandstand. I mean there wasn’t anyone trying to trip you up with different changes, no one playing faster than you can handle it, and no one playing more courses than the tune demanded. Certainly, there was professionalism. We were always on time for the gigs; we were always at the hotel to check out together, and we always got to the airport on time. And I think the third thing was that everyone recognized that there was a “standard” library. And it seemed to be mandatory that the players knew a pretty good percentage of that library. If you didn’t know certain songs that we considered as part of the library it was difficult to make jam sessions with, which is where you start to network. And a fourth thing was the eating habits begin to change in terms of the kinds of junk food we ate and how often we ate meals or how often we didn’t eat meals, and those things we still do today.

iRJ: When you joined the Miles Davis Quintet, did you know then that something magical was happening?

RC: Not at all. No, this man, who was just a guy at the time, was putting together a new band because the old band at the time was going their own way, as good bands always do. The guys get good, and they decide that we can do this on our own and they do it. Well at the time that I came along, Paul Winton and Jimmy Cobb were going back to Wes Montgomery Quartet, so that left a whole new band necessary, and I was one of the guys he asked to be a participant in his group.

iRJ: Were any of those recordings with the Miles Davis Quartet rehearsed, or was it all improvisation?

RC: Well, it’s kind of a difficult word right now in this type of discretion, improvisation, because that’s what we always did. If you mean how much of the ensembles were rehearsed and how well did we know the melodies and the changes, not very much. We generally went in there and played the recording sessions cold. I always regretted that we didn’t get a chance to develop those songs further. I thought that that was some great stuff that we could have gotten out if we had the time or had taken the time or had had that as our focus.

iRJ: Did things change or did relationships suffer because of your departure from the group?

RC: No; they remained my friends, we just didn’t play together often. The relationship, it wasn’t strained because I left, or it wasn’t strained because Tony left, or it wasn’t strained that the band went it’s own way; its what development is all about. You get a bunch of guys together and they play well and they realize that ‘let me try my own stream or my own limb from the tree’ we’ve all created here. And it’s always good luck and I’ll see you around the corner or we’ll stay in touch. I mean I called those guys every holiday because I wanted to know how they’re doing. I miss talking to them, and I clearly missed playing with them. And I want to let them know that for as far as they are physically away from me, they are still in my thoughts.

iRJ: You played the electric bass for a period of time and then you put it down and stayed with the acoustic bass. Why is that?

RC: I just started to find out what the upright could do. And I knew that to be a New York thing at the time, all upright players had to play electric because the producers of the jingles and commercial music was just realizing that there is another sound that they could contend with in their product. But to be competitive, one of the young players that would come along would take as much time to develop something; whether that was on the electric bass or the upright. And I thought that I didn’t have the time, that I didn’t have the man hours and I already started a view of what I could hopefully get the bass to do for me. I thought that I couldn’t be competitive and I’m a very competitive person as far as performance level is concerned.

iRJ: At one point you started to work with groups like A Tribe Called Quest, and the Red Hot Riots. In working with these groups in other genres, what do you think you all gained from one another?

RC: I think one of the things we shared was how can we make this seemingly unusual pairing be musically valid. It wasn’t about selling records or getting famous, it was about can we make this acoustic instrument play with the rhythms that we have to make this poem work. And it seemed to be a pretty decent experiment and I was all for being a scientist and being curious. And I think that everybody was happy with the results.

iRJ: A lot of the younger musicians are blending jazz with other genres of music. Do you consider that to be jazz or another form of music?

RC: I think it’s another form of music. The problem with most of those kind of non jazz written songs is that they are not written necessarily to be improvised on for eight or nine minutes. I mean, once you finish the lyric which is usually pretty great, and not too complicated a song form, it kind of forces the jazz player to add enough of his own thing to make it work. Many of those songs, for as great as they are, it seems to me, that in the pop world [those songs] are not geared for the kind of improvisation that jazz players deem necessary to make that song work for them and their particular music field. One of the things that we were always faced with back in the 80s when those things became popular was ‘how can you make a popular song have some legs musically, when it’s only written for two choruses of singing and then they take it out’? You know? We’re still kind of battling that issue I think.

iRJ: Some argue that jazz needs saving because it isn’t a popular art form. What are your thoughts on that?

RC: Well as long as guys keep playing, jazz doesn’t need saving; the audience needs saving.

RC: Well as long as guys keep playing, jazz doesn’t need saving; the audience needs saving.

iRJ: What challenges do you think a young jazz artist has in this new landscape of music?

RC: Well I think several problems are really clear to us. There are no record stores. And I think a lot of records or CDs were sold when people would just go into these record shops and just browse. They would see a record by someone they didn’t know or that they hadn’t heard or weren’t familiar with, and this walking tread made those places survive. Now that those places are not there, for whatever reasons they are gone, it makes it difficult to connect with a strange audience who would normally stumble on you going to record bins and going to cut outs. The other thing is that radio play of this music has diminished. There used to be many stations that are no longer playing this music. Because there are so few available outlets, being radio in this case, that makes it difficult for a young player to establish a presence through that specific medium. The third thing is that because there is not a record buying public as such, the young artists’ chance to make a connection with a major label to get the promotional support and the financial support and the connections that those labels provided in the 60s and the 70s, is no longer there. So these artists are going to the small independent labels hoping that they will be a step to get them a gig where they would not normally have that advantage.

iRJ: When you think back to the great musical groups you worked with in the past, do you think the landscape of artists is the same today?

RC: Well I think there aren’t as many groups; everyone wants to be a leader and not sacrifice their career goals to be a side man for a while to understand how being a leader really works. So I think that the number of what you’d call great groups, has diminished because of that primary reason.

iRJ: There aren’t that many jazz singers today. Do you think that jazz has abandoned the jazz singer? Was there ever infighting between musicians and singers in jazz?

RC: I think when you put the two in a separate category that is part of the problem; you can’t do that. Having said that, the things that come to mind are playing with Carmen McCray and Shirley Horn, Blossom Dearie, Sarah Vaughn, people whom I’ve had great contact with-not just enjoying listening to them, but also playing with them. One of those things that those people I mention had in common was that they were great piano players. And not having heard many singers today, because I just don’t have that kind of time anymore, I’m not sure that the current group of singers has that kind of keyboard skills which takes them to a level above being a singer. So that may limit some of the opportunities because musicians kind of get impatient about a guy or a gal who comes in and doesn’t know what key they are singing in or tempo, or what a chord progression is. And that makes it difficult for the singer to become part of a theme with that kind of limited musical knowledge and that kind of makes them be a part from a bunch of guys or the band. But I think that the more singers become aware of doing more than singing, become aware of needing a greater breadth of music and music skills, then they will find people who want to spend some time with them because they have a common ground now.

iRJ: Don Cheadle is starring as Miles Davis in the biopic Miles Ahead. Since you have a direct connection to Miles Davis, will you have any input or will you have any role musically in the soundtrack for the film?

RC: No one has asked me or volunteered anything about this movie. I am just as aware of this as I am a box of Corn Flakes. It exists, but that’s all I know, you know? So my input is talking to you right now. And you probably know more about it than I do. And that’s ok. But to answer your question, I can have no effect because I have been asked for no input.

iRJ: We just lost Horace Silver. Do you have any thoughts that you would like to share about him?

RC: One of the things that I was doing when I was teaching undergraduate school was that I had some small, beginning player, jazz ensembles. And one of the things that I always brought to these classes was a book of arrangements of Horace Silver’s songs-“Songs For My Father,” “Nica’s Dream,” “Room 608,” because I wanted these young players to understand what it took to make a quintet sound like a sextet. And what it took to make a chorus of two horns sound so well written, that you didn’t need to make an arrangement of it. Just play the tunes and notes this guy wrote and they will work for you. I made a couple records with Horace, and he became one of my really close friends during the time he was making records and I, as most musicians who knew him, am sad to see him no longer part of our physical life, but he’s still part of our memories.

Ron Carter will performing at the Newport Jazz Festival on Saturday, August 3, 2014

Words by Steen Burke