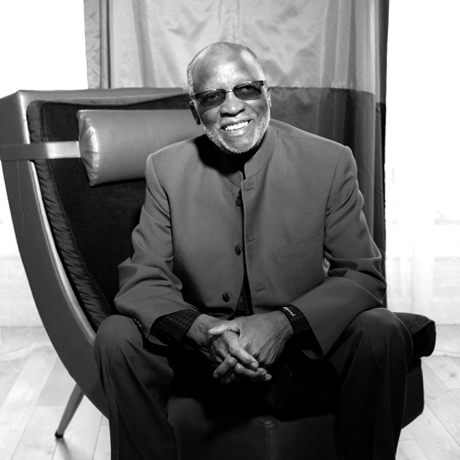

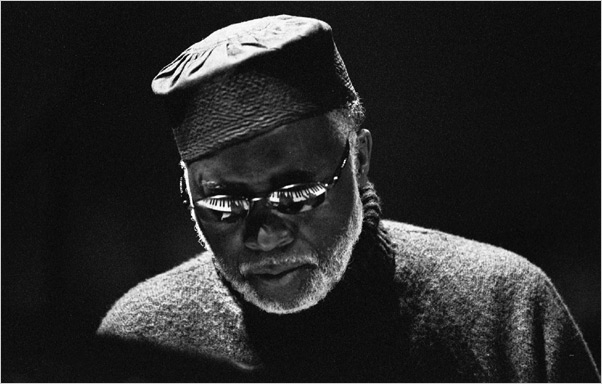

clas·sic /klasik/ adjective

1. judged over a period of time to be of the highest quality and outstanding of its kind.

Synonym: Ahmad Jamal

Playing the piano by the age of 3, composing at 10, and performing at Carnegie Hall with Duke Ellington at 22, Ahmad Jamal has proven that he is indeed classic in every sense of the word. Hailing from Pittsburgh, the city that produced such greats as Art Blakey, Stanley Turrentine, and George Benson, the great Miles Davis credits Jamal as one of his influences. As for Jamal, he credits saxophonist Ben Webster as one of his greatest influences, although on the subject, Jamal states that, musically, he is influenced by, “Anything that speaks of genuine purity and profound thinking.”

Never one to mince words, and in classic form, Jamal sat down with an iRock Jazz interviewer for a candid discussion about roots, racism, restaurants, revolutionaries, and remembrance.

iRJ: You were born in Pittsburgh, but your 2nd home is Chicago. How would you define the Chicago sound regarding jazz?

AJ: Well you know, a lot of us were struggling artists; a bunch of us were struggling musicians at that period. And the scene was terrific. Terrific scene. It was very profound, very prolific, and very provocative. And very energetic to say the least. That’s where I found one of the most talented drummers in the world…Vernel Fournier. I could go on and on and on about the scene in Chicago. It as terrific

It was the age of the tenor saxophone though. Gene Hammons and a bunch of these great tenor players were out of Chicago, so that was the age of the tenor saxophone then. I could go on and on about Chicago. (Laughs) very alive and very energetic and very influential the world over. Somewhat like my hometown of Pittsburgh. We’ve had some wonderful monumental figures from Pittsburgh, but Chicago is my second home, but Pittsburgh is my numero uno. My first home.

iRJ: In the 50s and 60s and during the time of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, what was it like going over to Europe, and how were you received their by the European audiences in comparison to your position as an African American musician in the United States?

iRJ: In the 50s and 60s and during the time of the Civil Rights movement in the United States, what was it like going over to Europe, and how were you received their by the European audiences in comparison to your position as an African American musician in the United States?

AJ: Unfortunately, there is a world of difference between the presentation of this music in Europe and the presentation of this music in the United States. I can go to Europe and I hear Duke Ellington on the tube. I hear myself, and all these other programs. An example of what I’m talking about is the hiatus that many of our artists made to Europe. Sidney Bechet left New Orleans and never came back. He’s a national treasure in France. He’s “Bird” in France. Never came back. Bud Powell, Dexter Gordon, Ben Webster, Thad jones, all them went to Europe. Johnny Griffith at the height of his career, he went to Europe and never came back. He died there.

Unfortunately, the presentation in Europe certainly is like night and day compared to the presentation here. When I do the Olympia in France… George Coleman and I, we did a concert at the Olympia and the marquee lit up. Ahmad Jamal, George Coleman, all my men, their names were on trailers. You won’t ever see that here, unfortunately. We don’t appreciate this art form. The only two art forms that developed in this country, in my opinion are American Indian art, which still is pushed in the back, still not promoted, and this thing called jazz.

Jazz promotes itself; it doesn’t hold a high place on commercials, or television. You could sell a Toyota just as easy listening to John Coltrane as you could listening to that junk that they present. Chewing gum for the brain. That’s what it amounts to the music that’s presented, if I may use that quote. But the fact is, unfortunately, the art form that has put America on the map and has been used in diplomatic circles, in state department tours is not appreciated. That’s the reason we have musicians who go and never come back.

iRJ: Do you feel safe traveling around the world today? Is it safe now?

AJ: It’s interesting. Let me put it this way. It’s interesting. Traveling in the south, for example, at the height of my career, I was a headliner, and we were doing a lot of Afro American colleges in the early 60s when “Poinciana” was at the top of the charts. It stayed on the charts 180 weeks. I did a tour with a group called the Hi Lows, a Caucasian group. Very great singers. They shared the bill with me, but I was the headliner. On our bus, when we emerged from our bus to eat in the 60s, there were two lines. My group going to the left, their group going to the right. You know why? We couldn’t eat in the restaurants. This is as late as the 1960s. I came through years later, and I decided to drive instead of fly with my group. I couldn’t eat at the restaurants until I got back to Chicago.

Now, have things changed? Yes, they have changed, but we still have a long way to go. Look what just happened with the NBA. Look at what happened. Ok, so is it safe, let me put it this way: it’s safer, but there are still some things that still have to be dealt with. You wouldn’t believe some things that have happened under Obama’s watch, under Bush’s watch, and it needs to be addressed. It’s safer, but we have a long way to go that’s all I can tell you. I just turned down a very big thing in the Ukraine, a really big thing, lotta Moolah, but I turned it down because it’s not safe. It’s not safe for me to go.

iRJ: You were the first African American to own a business, a club on Michigan Avenue, the Alhambra in 1960. Tell me a little about why you decided to do it, and why you ended up closing it a year later.

AJ: I’m still trying to answer that question. Why? [laughs] cause I was young and foolish. Very ambitious. Well, I had a lot of people talk me into doing that. That’s what happened. We were very, very successful. I had just made that monumental record “At the Pershing” and it sold a million copies. So we were very successful enough to buy a building on Michigan Avenue. I was very influenced by talk around me do this do that, so I think that was the main reason. I was listening to others. That’s why I built the restaurant.

And why did I close? To answer your second question: because I relocated to NY. I was overwhelmed in the restaurant business. I didn’t need 43 employees (Laughs). I opened and closed. It was open for a minute and that was it.

iRJ: Both you and Miles Davis had great admiration for each other, and you all both have something in common because you were both leaders. You were never a side man. In being a leader, how would you define yourself as a band leader?

iRJ: Both you and Miles Davis had great admiration for each other, and you all both have something in common because you were both leaders. You were never a side man. In being a leader, how would you define yourself as a band leader?

AJ: A bandleader? Not very mature, or very confident. It took many, many years to arrive at this stage. I didn’t make myself a bandleader; it made me. It chose me. It was a natural transition. I was working with a group called the Four Strings with Joe Kennedy that marvelous violinist, the late Joe Kennedy Jr, he’s made his transition now, but at that time in the late 40s early 50s, we had a group called the Four Strings. We were in Chicago and couldn’t get any work, so he decided to go back to Pittsburgh and start teaching. Then he became superintendent of music of all the high schools in Richmond, Virginia, and I inherited the role of leadership, and the Four Strings became the Three Strings because the three of us were left, and I became the leader. So leadership chose me; I didn’t chose it.

iRJ: Your advice to younger musician was really four key points: Perform, Teach, Conduct and Compose.

AJ: How’d you know that? Where’d you read that?

iRJ: [laughs] I did my homework.

AJ: [laughs] You sure did. You sure did. You certainly did.

iRJ: Of those four key points, is one more important than the other?

AJ: Seek knowledge wherever you can find it. That’s the important thing. The acquisition of knowledge on whatever level, in whatever category is the most important thing. My favorite thing is, prepare yourself to have more than one exit door because if a fire breaks out, you might get trampled to death if you only have one door. If you have options, then you don’t get frustrated when one of those areas of expertise breaks down and you can’t get what you want. So the only way you can acquire that is to have knowledge of many things as it pertains to music: teaching, conducting, writing, and performing.

iRJ: There are a lot of young musicians, Robert Glasper and a few others that are out there right now producing music today that a lot of the elder statesmen may not consider to be jazz, but it’s music. How do you feel about that and their effects on music today as it relates to people’s perceptions about what jazz is?

AJ: That’s a very good question. The fact is, I listen to all that’s good. I am perhaps the most sampled musician in the world my “Swahililand” has been sampled, sampled, sampled. I’m still trying to collect some of the money that’s owed me on some of these samplings, so my mind is open. The only thing I’m listening for is a statement. That profound statement that was made by the revolutionaries. Who are the revolutionaries? People like Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Thelonius Monk’s “’Round Midnight” that’s a statement. The question I ask of all these wonderful players, wonderful young talents is simple: What statements are being made that are gonna be revolutionary? That’s what I listen for, ok? That’s what I listen for. We can expand on these all we want, but the question is, out of all these great things that are being performed and put out, what profound statements are being made that are revolutionary akin to that of Charlie, Dizzy, Duke Ellington and people of that magnitude?

iRJ: Who’s on your radar today that’s making a statement?

iRJ: Who’s on your radar today that’s making a statement?

AJ: I am mentoring, if I may, some youngsters, from Berklee and some who have come out of Berklee [College of Music], who are phenomenal. There are three prominent people that are making statements that have caught the attention of many people. One is Esperanza Spaulding, the other is a pianist that I pushed some buttons for Hiromi [Uhera] the Japanese pianist, and now I’m mentoring a young wonderful guitarist who is in the same category of brilliance, Zayn Mohammed, a brilliant guitarist, graduate from Berklee, London born, and he’s one of the three that are making, and approaching that level that I’m talking about. Those are three, and there are others, but these are three that come to mind immediately if not sooner.

iRJ: How would you like your legacy to be left? How would you like to be remembered?

AJ: You’re remembered by how you live. You’re remembered according to the way you live. That’s it. It’s as simple as that. So however I lived, that’s how I will be remembered.

Words by Geveryl Robinson