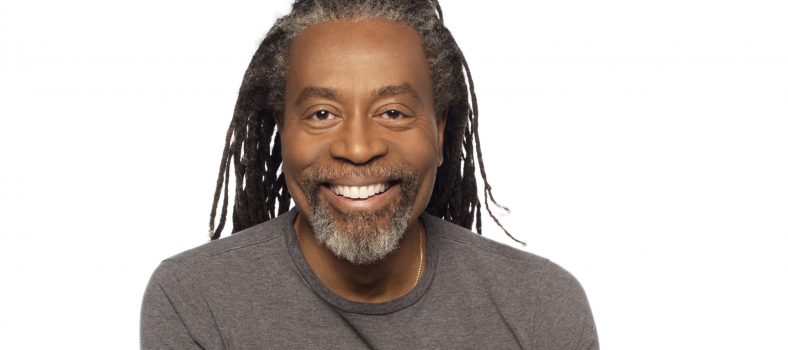

“I don’t use songs as a vehicle to glorify myself. I’m going to play whatever is required to make the song successful.” These are the words of Branford Marsalis. He’s a man that understands that it’s not all about him. Considering the big names he’s played with from Sting to Gang Starr, and all the hit songs he’s played on, it’s a wonder that he hasn’t gotten a big head, but the truth is that in the realm of jazz, it’s easy for some to get caught up in their own ideas and try to show them off to whomever is listening. Marsalis, however, takes no part in that line of thinking, and it’s a main reason why he’s been as successful as he has and why he continues to grow and educate others in that the music is more important than the musician.

Marsalis has long considered himself as a musician rather than as a saxophonist. In his mind, there is a big difference between the two in that a musician is someone that knows what it takes to make a song reach its highest potential, even if it means not playing as fast as one can or as many notes as is possible. “For the instrumentalist, the instrument is the center of their life; for a musician, the music they play is the center of their life,” Marsalis explains to iRockJazz. “In order to play music and communicate with people you have to have something in common with people. Most people don’t spend eight hours a day or four hours a day in a little cubicle working on complicated devices to play on stage. ”

Marsalis spent his childhood playing in funk bands as part of the horn section and grasped the concept of knowing his role. This method of thinking led him to lend his instrument saxophone to some of the biggest recordings of the late 21st century, such as Shanice’s pop smash “I Love Your Smile” and Public Enemy’s iconic anthem “Fight the Power.” “First of all, I don’t go up there playing jazz solos. I employ jazz sensibilities and it’s unique and it’s different in the way it sounds, but I understand my role in that situation.”

Many jazz artists have elected to stay in their lane, not venturing far away from the realm of jazz. Marsalis’s ability to do well outside of jazz draws from his multi-tiered interests, which not all jazz musicians have. As a member of a musical family, expectations are high, especially when you grow up in a region rich with musical history that has a storied reputation for extractive musically-inclined progenies. “That’s what it means to grow up in New Orleans,” Marsalis tells iRockJazz. “I can name off the top of my head 12 families where there are 3rd and 4th generations of musicians coming from them.” Indeed, with a town that’s home to the Alcorn’s, the French’s and the family of rising star Trombone Shorty, the Marsalis’s had plenty which to live up. Although he, along with his dad and three of his six brothers, have excelled at their respective instruments, Marsalis and his family have refused to let music be the end or be all of their everyday existences. “We had a house of four – four out of the six –rambunctious-assed boys. Wynton was a national merit scholar and had scholarships and free rides to Stanford and all these other places. It’s hard to do that if all you’re doing is playing music all day. I was on the debate team, and Wynton and I played sports.”

Being well-rounded at a young age helped Marsalis keep himself from being consumed by what he feels are unnecessary, unwritten restrictions and regulations that many jazz musicians become enamored with: getting wrapped up in the science of jazz and establishing theories, hypotheses and systems that will make them stand out from their contemporaries. Marsalis’s openness to working with other artists also comes from an exchange of musical ideas between him and a group of four friends during high school. Together they’d share an open dialogue about music of all sorts and had a literal exchange of music between them. “Because I went to white schools I learned about Led Zeppelin and King Crimson and Elton John,” Marsalis explains, “but they didn’t want to hear no James Brown or Aretha Franklin. And I’d go home and [my brothers] didn’t want to hear no Elton John or King Crimson. So there were five of us and we would sit around and learn music together.” They’d all take turns introducing each other to Jimi Hendrix, King Crimson, The Jackson 5 and Stevie Wonder, a critical component to Marsalis’ approach to music and an approach that’s made him a unique player for over thirty years.

Although Marsalis has had notable success contributing to music from other genres, he still plays jazz most of the time. However, as the title of his exciting new quartet LP “Four MFs Playing Tunes” indicates, he employs his same practices in jazz, or lack thereof. His attitude toward practicing may not be one that is shared by his contemporaries, but it’s something that has worked well for him. “I didn’t start practicing an instrument seriously until I was 36,” Marsalis reveals. He was content with the music he was playing in high school, which wasn’t as strenuous as jazz can be. It wasn’t until he got some family inspiration that he decided to explore jazz further. “I went to Berkelee for production and heard Wynton [Marsalis] playing with [Art] Blakey and decided I wanted to play jazz, which surprised my whole family. They said, ‘Really? You never wanted to play before.’ I was a really good horn section player. And my dad would always chide me for practicing. I said, ‘the music I play doesn’t really require practice, so why should I practice? I don’t like it that much.’ I don’t like it now, but the music that I’m dedicated to playing now requires that I practice, so I do.”

One of the main reasons for Marsalis’s idealism towards practice goes back to his realization that it’s more important to communicate with the listener, who more often than not leads a modest existence. “I was better prepared as a musician when I spent time working at Burger King and Baskin-Robbins than I ever would’ve been going to a conservatory at the age of 14, 15, or going to jazz camps,” Marsalis goes on. “At the end of the day, regardless of what the music is, the music is about people, whether they know it or not, or whether they appreciate it or not.”

This unique path that Marsalis has led eventually got him a big gig playing with Sting’s solo band at age 25. At the time – 1985 – he wasn’t as good as he is now, but he felt he didn’t have to be because of the type of music Sting needed from him. “I was a good musician. I was a lousy sax player, but a good musician. And I grew up in an era full of really great saxophone players who were lousy musicians.” Marsalis believes that it’s more important to give the song what it needs rather than waste the performance by showing off. In his mind, masterful saxophonists are certainly technically able to do the task of playing, but they’re not philosophically inclined to execute it well for the particular purpose for which they are playing. “Clarence Clemons was not a great saxophone player necessarily like all these other guys who are great saxophone players,” Marsalis says. “And if [Bruce] Springsteen gave the other guys a chance to play a solo that was going to work in Springsteen’s particular setting, they would fail because they would all have their saxophone devices and yet not have what that song needed. That song needed somebody that was gonna give a plaintive wail at the right time in the right setting and Clarence was perfect for that. As long as you have people who play instruments who sit around and analyze every song harmonically and they don’t really hear the song, they’ll never be able to play like that.”

Marsalis’s success during his time with Sting draws a great deal from a rude awakening he got from playing behind a female vocalist as a teenager, eager to show of what he was made at the time. “I started playing some ole fancy stuff and the singer cut me off and said, ‘Don’t ever play bullshit behind me.’ I went home and told my dad and he said, ‘Well, she’s right. The thing you have to understand about singers is that the singer’s in front; the singer’s the star. And if you don’t like the fact that the singer’s the star, don’t work with singers.’ Anything you do to upstage the singer defeats the purpose of the music. And, while he’s learned jazz music from his father, pianist Ellis Marsalis, Jr. and his brother, Wynton, Marsalis attributes a good deal of his wisdom from the lessons he’s received from afar from other legendary jazz heroes of his. “What I do is I use the greats of this music as a constant point of reference, and when I do I always come up short so I gotta keep working.” Specifically, Marsalis used saxophonist Wayne Shorter as a template for his principle behind serve the song over self. While in Miles Davis’s quintet, Shorter gained his legendary reputation playing with rapid fervor. However, for his records with Weather Report and Joni Mitchell, Shorter switched up. “He played just enough notes to make the song better,” Marsalis reveals. “He didn’t use the song as a vehicle to say, ‘Look how fast I can play; look how many notes I can play.’ What’s interesting about that is when you’re doing that you basically play to the smallest crowd possible, which is the other musicians.”

When it came to improving his personal style, Marsalis also looked to John Coltrane, as many others do, for guidance. In 1994, Marsalis recorded Coltrane’s “Resolution” – a tour-de-force composition from Trane’s celebrated 1965 album A Love Supreme. It turned into a moment of crucial reflection for him and his ability. “The first time I tried to play that, it was an abysmal failure,” Marsalis remembers. “If you put on that Red Hot and Cool record – the fake jazz record that they claimed was a jazz record, but wasn’t – we did a truncated 18-minute version of it and it was just the saddest shit in the world, and it was very informative for me. ‘Well, this sucks. Now I gotta figure out why.’” What Marsalis figured out was that he wasn’t equipped with the knowledge about what it takes to play the blues the way Coltrane did, not to mention “playing with sustained intensity and control for long periods of time.” It took Marsalis years, but by 2001, he felt he got it to the way that it was considered as “the real deal.”

In today’s jazz landscape, many young artists like Robert Glasper and Christian Scott are getting a lot of attention due to their fusing of jazz and hip-hop. Marsalis’s contribution to the cross pollination of the two genres came at an incredibly critical time, when hip-hop was still fighting for legitimacy with the masses. Not only did Marsalis play on Public Enemy’s 1988 anthem “Fight the Power,” but also collaborated with duo Gang Starr for the Mo’ Better Blues soundtrack, and later with its emcee Guru on his 1993 solo hip-hop/jazz hybrid Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1, which includes fellow jazz artists Terence Blanchard, Lonnie Liston Smith, Dr. Donald Byrd and others. Marsalis actually had personal friendships with Gang Starr, so much so that at one point they all lived together for a time in New York. Marsalis recalls, “I remember when we were doing “Jazz Thing,” and right while we were [recording] it, they got evicted from their crib in the Bronx. So, I called my first wife and said we’re gonna have company. She asked, ‘How long?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know. A few months.’ So Keith (Guru) and Preem (DJ Premier) lived with us, and we talked a lot about the business, about the profession, about the whole thing.” During the time they all lived together, Marsalis tried to school Gang Starr on the importance of music publishing and other things. In his view, their different backgrounds, dialects and slang made for some interesting exchanges. “It would’ve made a good movie,” Marsalis reminisces. “It was kind of like that Barbara Billingsley character in Airplane! When she says, ‘It’s okay. I speak jive.’ I knew what they were talking about, but I would respond in my language.”

While Marsalis’s contribution to fusing hip-hop with jazz cannot be overstated, he contends that the action was not as deep for him as it can be for others, and another example of his openness to playing within other sounds and genres. In actuality, Marsalis feels that the differences between the two worlds aren’t all that wide, but it doesn’t mean that they’re two sides of the same coin. If anything, Marsalis believes one of the biggest differences between jazz and any other genre is the participatory factor when it comes to the audience. One of the reasons people don’t go to jazz shows often is because the audience can’t participate the same way they could at a pop show. “That’s why people say, ‘I’m going to see a concert,” Marsalis explains. “They don’t say I’m going to hear a concert.” He once illustrated this point with one of his students. When the young man tried to advance his theories about the coloration between Hip-Hop and Jazz, Marsalis showed him otherwise through a field experiment at a concert the student was attending. Marsalis gave him a Dictaphone to put in his pocket and record the first hour of the show.

“We put [the tape] on and the first thing you hear is talking, and you hear it throughout the performance—talking, talking, talking:

‘Yo, what’s up, dude?

Yeah, what’s going on?

Shit is jammin’, ain’t it?

Yeah! Shit is dope!

Oh, that’s my jam. Fuck yeah!’

And then they start singing the song. The music is participatory, which is one of the main reasons that people like it. Ain’t nobody going to tell them to sit down, shut the fuck up and listen. They getting their drink on, some of them’s high, some are trying to get some ass, they’re singing the song and everybody’s having a good time. If they would listen to it in their living room with a glass of wine as opposed to bumping their head to it in the car while they’re going places, their idea of what it is would change dramatically.”

The student was despondent after hearing the results, but Marsalis explains that he wasn’t trying to tell him Hip-Hop was bad, but that he shouldn’t try to combine things that shouldn’t be combined and take the music for what it is.

Marsalis has made a brilliant career taking the music for what is it. Rather than getting caught up in the competition and trying to elevate jazz, or himself, as higher than other American music genres, he allows everything to be what it is and plays within the musical structure accordingly. It can be summed up in an analogy to his fascination with action-packed movies, an admiration that draws much teasing from his wife. “I like shit that blows up,” Marsalis admits unapologetically. “I don’t equate that with being the top tier of great filmmaking, but sometimes I would gladly walk away from a film that is well done, well-written and well-acted to just go see a movie where shit is blowing up all over the place, because I’m a guy and I like that kind of stuff. And I don’t need to make excuses for it. But there’s no way I’m going to say with a serious face that The Avengers is one of the greatest movies of all time. I’ve seen Orson Welles’s films; I know it’s not the greatest movie of all time. Where I feel I’m lucky is I don’t feel the need to justify my tastes to anyone.” And that’s also why Marsalis has been one of the most in-demand musicians for the past three decades. He makes no excuses and makes no justifications for his work.

by Matthew Allen