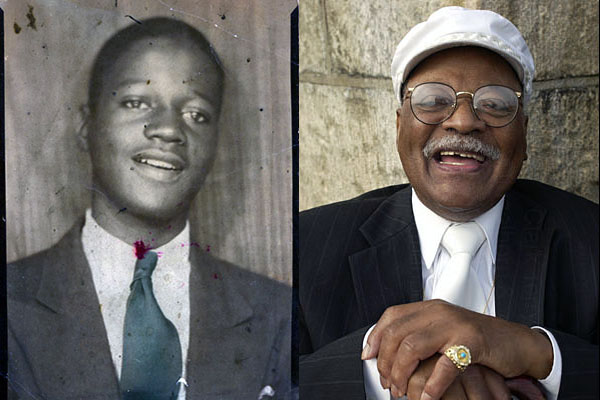

Legendary Trumpeter Clark Terry

Legendary Trumpeter Clark Terry

“If Clark Terry told me I was playing shit, man, I’d take that seriously. I’d take it to heart.” – Miles Davis

Musicians can be a selfish or cryptic people. Even though it may or may not be a fair assessment to make, the truth of the matter is that many of them are, and for good reason. Musicians work very, very hard at learning their respective instruments, understanding composition and mastering improvisation. Then, they have to work that much harder at getting people to notice them – fans, potential band mates or bandleaders, record companies, management, and more.

Once they’ve obtained all of which they wanted, at whatever level they are content with, then the truly difficult task begins, which is keeping it all for themselves as long as they can while other musicians move up the ranks, fighting for position. So, after all of that, they want to keep it for themselves, afraid anyone who comes along will take their shine, or they may just want the youngsters to prove that they’re good enough by learning on their own the same way they did. Clark Terry’s early life encounter with such a musician was the catalyst that put him on a selfless path that helped make him the living legend that he is today.

Terry, one of the world’s most prolifically recorded instrumentalists of all time, carved a place for himself thanks to his signature voice on the trumpet for over seven decades. One of the ways he honed his craft was on trumpet by modeling his sound after two other instruments. “I wanted it to play like a violin,” Terry explained, holding notes longer and he did so by mastering circular breathing – a method that allows continuous air to flow by inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth simultaneously. The other instrument sound that captured on his trumpet was similar to the flugelhorn, which Terry felt had a very, very mellifluous tone. “I used my tongue to [bum bum bum bum bum]. Then I’d triple tongue, single tongue, double tongue, doodle tongue and flurry tongue.”

Terry possesses the mark of a true original. His signature sound is detectable within mere seconds of listening to him play – and yet one of his most important contributions to music has been his undying willingness to pay it forward, educating other musicians along the way, such as Quincy Jones and Miles Davis. Ironically, it was a deceptive incident with an older trumpeter that started him on the path. Decades before Jones would come knocking on Terry’s door as a 12-year-old, Terry tried to get advice from a local veteran trumpeter about playing better in the lower register. “He told me to go home look in a mirror, wiggle my left ear and grit my teeth,” Terry told iRockJazz. Eager to do whatever it took, Terry did just that and in fact learned to wiggle his left ear before his brother-in-law and trusted mentor Sy McField told him the advice was indeed incorrect.

Clark said,“I thought he was giving me the right advice.” This occasion was just one example of how many other veteran players kept things close to the vest. “Oh, most of those cats didn’t have time for young people.” It was from that point on that Terry vowed that he would do all he could to help anyone who needed his help.

The foundation of Terry’s penchant for educating came from his love of sharing what he learned. While always dropping knowledge to others, Terry’s knowledge escalated in the bands of Count Basie and Duke Ellington. He spent nearly four years playing in the Count Basie Orchestra (1948 – 1951), an institution in American Jazz, where he learned important tools. “He used a lot of space and time when he played,” Terry said of Basie. After leaving the band, he moved on to play with the Duke until 1959. Terry, according to his autobiography, Clark, refers to Count Basie as “prep school for the University of Ellingtonia,” picking up great wisdom from Duke and his innovative approach to arrangement and composition. “He was just that much more far ahead of what everyone else was doing.” From there, Terry joined former pupil Quincy Jones’ big band for the 1960 European tour of “Free and Easy.”

“The greatest honor I’ve ever felt in my life was when Clark Terry left Duke Ellington to come play with my band,” Jones testified in his book “Q” on Producing. “Can you imagine what it felt like to have the guy who taught me when I was 12 years-old leave Duke Ellington’s band to come play with me? It was incredible!”

Terry’s generosity didn’t stop at fellow trumpet players. Four time Grammy-winning vocalist Dianne Reeves was also a recipient of Terry’s knowledge. “He’s a genuine, giving spirit. He loves what he does and he loves to share the knowledge of what he does. He’s always been that way,” Reeves spoke of Terry, who gave Reeves his number after hearing her sing at a Chicago National Association of Jazz Entity. Soon after, Terry was surrounding Reeves with top musicians to help enhance her gift. “I always laugh, because I didn’t know who they were, but I knew they were amazing. He always wanted to expose me to the best.”

Today, Clark, 92, continues to teach and play, despite losing both his legs last year due to diabetes related amputations. Although he is in constant care, he refuses to slow down. He’s a prominently featured instrumentalist on Teri Lyne Carrington’s 2013 album Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue and his horn will be found on rapper/producer/saxophonist Terrace Martin’s forthcoming solo debut 3 Fold Chord. Martin, who’s been heavily affiliated with prominent hip-hop artists like Snoop Dogg, 9th Wonder and Kendrick Lamar, was thoroughly impressed with Terry’s chops, tweeting during a recording session, “I’m recording Clark Terry…91 years young …he is killing this blues!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

(l-r)Alan Hicks on camera, Clark Terry, Terrace Martin, and Snoop Dogg

(l-r)Alan Hicks on camera, Clark Terry, Terrace Martin, and Snoop Dogg

Part of his continued work ethic in the face of his recent health issues has been his unflappable youthful exuberance. “He continues to do it even in the physical state that he’s in, it doesn’t matter,” says Reeves. “I always say, ‘Clark, how old are you,’ and he’d say, ‘I’m eight years old,’ and he keeps that youthful spirit. That’s the thing that keeps him moving forward.” At the end of the day, Clark Terry’s wish is that he’s remembered as an advocate of education and assistance in a world where so many refuse to help those who seek it. “Well, I want them to remember that I always had time for young people,” Terry said. “I always tried to teach young people, change a little bit of their life.” After playing for eight presidents, being the first Black NBC staff musician on The Tonight Show, and winning over 250 awards, honorary doctorates, it’s more than an understatement to say that his legacy is safe.

*iRockJazz would like to acknowledge Gwen Terry, Clark Terry’s wife and biographer, whose assistance and patience helped make this article possible.*

By Matthew Allen