The 1950s ushered in a new sound that changed the entire musical landscape in America. That sound was Rhythm and Blues.

The 1950s ushered in a new sound that changed the entire musical landscape in America. That sound was Rhythm and Blues.

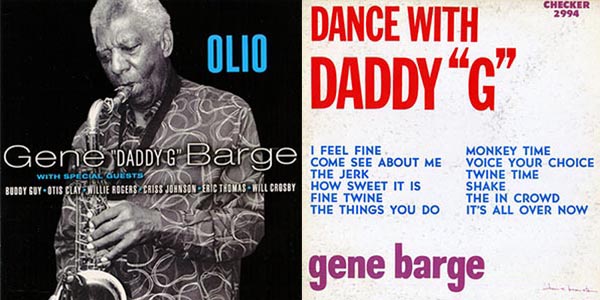

A natural product, as legendary saxophonist and composer Gene “Daddy G” Barge explains, of the integration of swinging jazz and rhythmic blues. Daddy G, a multitalented artist, is considered one of the pioneers of this new sound.

Born in Norfolk, Va., Gene moved to Chicago in the early 1960s. He began working for the world renowned Chess Records where he produced, composed and recorded with musical icons like Fats Domino, Little Milton, Bo Diddley, and Muddy Waters, just to name a few.

Subsequent to his tenure at Chess Records, Barge continued to work with musical giants like Natalie Cole, Buddy Guy and The Rolling Stones and even secured acting roles in eight major films, including: Code of Silence, Above the Law, Under Siege, The Package and The Fugitive.

Today, Gene “Daddy G” Barge is still keeping company with legends. The Chicago Rhythm and Blues Kings have been belting out Windy City Blues for over 20 years, and Barge, who produced three of their albums, plays select gigs with the band. This August, Gene “Daddy G Barge will join the band on the main stage of the Ships and Shore Blues Festival.

With such an astonishing resume, iRock Jazz had to speak to the legendary sax man about his historic career.

iRJ: You’ve had an interesting career. Where did music start for you?

iRJ: You’ve had an interesting career. Where did music start for you?

GB: My daddy started playing banjo with a band long before I was born, and I was influenced a little bit by the music that he was playing. I was in the school band when I was in junior high school and by high school, they had disbanded the band. My high school was Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk, Va., and there were some big football powers in that area and they needed to start the band again, so we started the band. So that’s basically how I got started. But I was more interested in sports than I was in music at the time.

iRJ: R&B started around 1953; correct?

GB: Well yes, but it actually started before that.

iRJ: What type of music were you playing before 1953?

GB: I was playing light jazz. I was in the college jazz band and I was in the marching band and I was a music major at West Virginia State College. Then I started playing with a band called the Griffin Brothers, which was an R&B and blues band back in the early 50s.

iRJ: When artists transition from one genre of music to another, or when a new genre of music is created like R&B, there is usually some kind of disruption. Did you experience any backlash or were people receptive to this then new genre of music known as R&B?

GB: Well, you know, this transition was just natural. Back in them days, you had the Griffin Brothers and the guys that were playing like the swing jazz and the blues; it was like a fusion of music had blossomed into a form of music that is now known as rhythm and blues. The media and a lot of those guys, named it rhythm and blues. It was a few years after the war and people were out dancing and jazz music in our community was kind of fading a little and then this music pops up and the small groups and the small combos and Milburn and all of these singers rose out of it. So there you have the rhythm and blues in the 50s going full blast. Fats Domino came on the scene and all of a sudden you have all of these blues groups and eventually it went into a sophisticated blues, which is R&B.

iRJ: Over the years, jazz has had to struggle to stay relevant. Blues seems to be dealing with that same issue.

GB: Well blues has been mostly saved by white people now. White people in their 40s and 50s, those seem to be the ones that turn out for the blues. My people, they are more or less into the more popular R&B and hip hop.

iRJ: Why do you think that is; considering the fact that blues was created by African Americans?

GB: Well you know the blues is more of a folk music, it tells a story. White people are more into folk music because they brought that (folk music) over from Ireland and Scotland and different parts of Europe, and that evolved into country music. Country music is folk music. They started telling all of these stories, all of these tales in a different ethnic light, and that is what became country western music. Our music came from our time singing in the church; from gospel music. Gospel music is what influenced rhythm and blues music.

iRJ: A lot of the jazz musicians during the civil rights movement, participated in the movement by creating music that can be considered anthems for those who fought for civil rights. Did blues musicians do the same thing?

GB: Sure; most definitely. You’ve got those in the blues and in rhythm and blues who were some of the most rebellious guys against the system. But most of the early rhythm and blues guys were rural musicians that came off of farms into music. They came out of the agricultural system and share cropping in the south, so they were definitely more rebellious and very vocal about the movement.

iRJ: Let’s talk about your time working at Chess Records in the 60s. Isn’t it true that Minnie Riperton started out as a receptionist and then became a background singer at Chess when you were there?

GB: Back in 1964, Minnie was in high school. And she was in a little group called the Gems. And they came by Chess Records, I think to try to get a recording deal, and right away they couldn’t get signed. But Billy Davis, who was the head of music at Chess at the time, kind of took them in and encouraged them to hang out to practice and rehearse and let them hang out. And then eventually, every once in a while, they started using them as background voices on some of the other artists that were recording at the time. So Minnie, was very talented on backgrounds, she could sing various parts on background. So they eventually recorded the group that she was in, but the group didn’t obtain any type of popularity as they had hoped, and Minnie stuck around as a background singer.

iRJ: At Chess Records, you worked with legends like Little Milton, Billy Stuart, The Dells, Muddy Waters, just to name a few. What was it like being a part of that? That was almost like working at Motown wasn’t it?

iRJ: At Chess Records, you worked with legends like Little Milton, Billy Stuart, The Dells, Muddy Waters, just to name a few. What was it like being a part of that? That was almost like working at Motown wasn’t it?

GB: Well it was. In fact Motown evolved out of what Chess was doing. The early association that Barry Gordy had with Chess was with the Barry Strong record “Money, That’s What I Want”. Billy Davis was working with one of Barry Gordy’s song writing partners at the moment along with Smoky [Robinson], and they were back and forth out of Chicago. So when Motown got hot in the 60s, Chess got hot too. So they were like competition. They were very competitive with each other. Motown evolved out of Barry’s ideas and his way of doing things, but the in house rhythm section-we had the in house rhythm section.

iRJ: You began working with Marvin Yancy in the early 70s and had the opportunity to record on some of Natalie Cole’s early hits, including “Sophisticated Lady”, for which you won a Grammy. How did you meet Natalie and come to work with her early in her career?

GB: Marvin Yancy was a young kid, around 20 or 21, and Inez Andrews the gospel singer, had invited me over to her house to possibly do something with her. So I said, “Well, I’ve never heard you sing.” So she said ok, and called upstairs and downstairs came Marvin Yancy. He was hanging out with her daughter. So Marvin and Inez’s young son – he was about 11 or 12 years old then, and is currently playing with Aretha Franklin – is her dependable keyboardist, Richard Gibbs. So Marvin came down and played, and that‘s when I met him. Then Marvin hooked up with Jesse Jackson’s brother, Chuck Jackson, and they became the team that ended up with Natalie Cole. I ended up with them doing the very first demo session with Natalie, downtown Chicago, at Universal Studios doing the four songs that got her started.

iRJ: Were you surprised that you won the Grammy and did anything change after that for you?

GB: I had been nominated for Grammys before because I had worked with Muddy Waters and Little Milton, these people were at the top of the charts then. I had gotten nominated with the John Clema jazz album at Chess and we didn’t win, but I was nominated-which was close. And I was involved with the Grammys. I was the vice president of the Chicago chapter, so I was involved with it for a long time. So it was like some of the stuff that goes with the business I guess.

iRJ: You also got to play in the rhythm section of the Rolling Stones. What was it like traveling with the Stones? And how much of an influence has blues had on their music, if any?

GB: Ahmet Ertegün, who was the president of Atlantic Records, and I had become friends. So he decided that he wanted to come to Chicago and do some blues and he called me and asked me what studio he could use because the Chess studios were closing. So I set up the session and everything for him. And before he came in, he said ‘incidentally, I’m bringing Mick Jagger with me. He’s going to hang out while I’m in Chicago.’ So we recorded for a week and Mick and I hung out for a week and that’s how I got to know him. So when he [Mick Jagger] left Chicago, I wrote him a letter and told him that if he ever needed a saxophone player to let me know. Ironically in 1981, Ernie Watts, the great saxophone player, did the American tour for the Rolling Stones and he quit. Around the time the tour was over, Mick decided that he wanted to tour Europe; and Ernie Watts didn’t want to make that tour. So Mick called me himself and asked me would I do it and that’s how it happened.

Here’s the thing about the Stones: Mick Jagger and them had been listening to and were influenced by the early recordings on Chess Records. In fact, Willie Dixon, one of the greatest blues writers ever, wrote a song called “Rolling Stone”, and that’s where they took their name from. When the Rolling Stones came to Chicago, they used the Chicago studios to try to capture some of that sound and they got their first single hit out of Chicago. They came back again the next year, in 1964. I wasn’t there at the time; I was still in Virginia. I was destined to come a few weeks later. But they recorded “I Miss You” with Sugar Blue on the harmonica, which was one of the big singles that helped to get them over in terms of worldwide popularity. So they were strongly influenced by what was going on at Chess.

iRJ: Buddy Guy is probably one of the most influential names in jazz today. How did you end up meeting him?

GB: Buddy Guy was hanging out at Chess trying to get a deal and he did some sessions with Willie Dixon. They were good friends. My association with Buddy came when Willie brought us together. One of the things we did together was “Wang, Dang, Doodle”. And from that point on, Buddy formed a band and I was in Buddy’s band and we performed in all of the clubs in and around Chicago. He wanted to do an album; he had already done some recordings, but he wanted to do an album. So I produced his first really good album called “I Left My Blues in San Francisco”. Buddy and I are really, really good friends.

SSBF: We lost “Big Time Sarah” (Sarah Streeter) recently. Do you have any stories about Sarah?

GB: Well, there are a lot of stories about Big Time Sarah. She used to come in and sit in with our band. This isn’t too long ago, we were playing a club called B.L.U.E.S. down on Halsted, and Big Time Sarah used to love to come in and sit in and sing with our band. She would walk in the door and want to sing a song with us. Big Time Sarah was a real character. She knew everybody, she had a few recordings, and she used to walk around and sell her records. I didn’t socialize with her on a personal basis, so I don’t know all of the Big Time Sarah stories. But I knew her as a singer really well and she liked my playing. I really liked Sarah.

SSBF: How does blues stay relevant with the younger generation?

GB: Blues influences the music today. It’s not the favorite music of the young folks today, but the music that they listen to is influenced by it; they just don’t realize it. The blues has been merged and integrated into the sound we have today. And the blues will always be with us, it will always be there. It just won’t be as basic as it was in the 40’s and 50’s. Who knows where the evolvement of the music will end up?

SSBF: The Chicago Rhythm and Blues Kings will be playing at the Ships and Shores Blues Festival in August. Tell us what audiences can expect to hear.

GB: The Chicago Rhythm and Blues Kings is an evolvement of Big Twists and Mellow Fellows. This is a hard hitting blues band that does R&B and the Blues. It’s a band that does music from the past with a modern twist to it. We think we play really well.

Gene Barge will be performing with the Chicago Rhythm and Blues Kings at the Ship and Shore Blues Festival in New Buffalo, Michigan on August 8th at 4:00 pm. More information about the festival is available at www.shipandshorebluesfestival.com

Words by Steen Burke