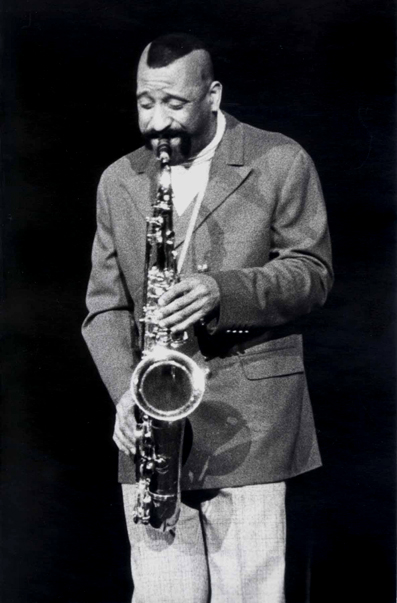

Sonny Rollins is a jazz icon. He has played saxophone with Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach, and more — and performed as leader of his own band on numerous influential recordings. In this recent interview with iRock Jazz, Rollins speaks candidly about his musical influences and training, the drug addiction that nearly destroyed him, and his lifelong pursuit of music and dignity.

iRockJazz: You were considered largely self-taught at the age of 17. Who were some of your mentors?

SR: I wouldn’t consider myself self-taught. As I’ve often said, when I got my first horn as a kid, I knew I would be a prominent musician. I was a big follower of Louis Jordan and his band. He had a hot R&B band, and he was my idol. I went to music school in New York City – just a little place called the New York School of Music – and every instrument you could name was on their list of instruments to be taught there. Keep in mind, this was just a little place upstairs over a store. I had a couple of teachers near Harlem, and then I studied with Joe Napoleon. I also paid close attention to this saxophone player called Foots Thomas – he used to be with Cab Calloway’s band. All these were guys on 48th Street – “Music Street” in New York City at that time. I received a lot of instruction from my idols. Everybody would give me advice to a degree. But, I had some formal teaching and help from people who were more proficient than I.

iRJ: How did drug use creep into the music industry? It is to my understanding that it was readily available. Would you consider this experimental, and did it get out of hand? Or, was it a way to find out about a different level of music?

SR: When you’re involved in anything connected to the arts, it’s very easy to try to enhance your ability to create by using something, whether it’s alcohol or drugs. A lot of people in show business tend to be susceptible to the use of drugs. It’s just the way it is. Some of the great leaders of that time – for instance, Charlie Parker, who was our prophet – were unfortunately addicted to drugs. And a lot of us thought, “Gee, if Charlie Parker does it and he plays so good, then it must be something that we can do for ourselves.” Therefore, we got into it for that reason by trying to emulate the guys who we admired. That was one of the big reasons that people like myself got involved with drugs.

iRJ: While on the topic of drug use by some musicians who felt they needed it to fuel their creativity, did you see that even these successful, genius musicians were wasting their lives, and that this was wrong? Did you see the dark side of it, or did you just see them as great people who were frail, being bent because of this addiction?

iRJ: While on the topic of drug use by some musicians who felt they needed it to fuel their creativity, did you see that even these successful, genius musicians were wasting their lives, and that this was wrong? Did you see the dark side of it, or did you just see them as great people who were frail, being bent because of this addiction?

SR: Yes! Another famous person of that day, Billie Holliday, also had drug problems. And it’s always been my contention that if Billie Holliday had never used one illicit drug, she would have still been great. If Charlie Parker had never used drugs he would still be great. Drugs are an add-on, not an intrinsic part of what these people are. That’s my opinion.

Now, the story with Charlie Parker: We were at a recording session – the first and only record session I had with Charlie Parker. He knew I had been using, but I had been away – incarcerated for that. I came out, but then I unfortunately went back to using drugs again. But Charlie Parker didn’t know. He thought I had straightened myself out. Unfortunately, I hadn’t. I had been using with a guy who was also in on the session we were doing. When I told Charlie Parker I was straight, he was so happy. Then, later on in the session, this guy I had been using drugs with the night before ratted on me. He told Bird I had been getting on, and I could see the disappointment in Charlie Parker. That’s when I realized that this isn’t such a happy life. I realized that using drugs and blowing your horn don’t necessarily go together. And with Charlie Parker, they didn’t go together. By that time, I only had two people in my corner. I had alienated everybody. I was a pariah. So, I went to get rid of drugs because of Charlie Parker and my mother. Those were the two people who influenced me in making that big decision that I was on the wrong path.

iRJ: With everything going on in the news and politics, what was it like growing up in the Bebop period in Harlem?

SR: The political thing was never very much in the forefront of jazz. It was kind of a barrier. A lot of us thought Louis Armstrong was being too accommodating of the culture, presenting jazz as sort of a little bit more than a minstrel show. This is the way it was in those days. Many of the young musicians like myself didn’t want to be seen as minstrels. We wanted our music to be seen as something very serious and recognized for the value it had. Young musicians like me followed Charlie Parker because Parker didn’t want to sing and dance. He was aware of the political injustices that are still around today. Things haven’t changed that much. Music to us was serious, so therefore, the politics of the culture came into it.

But when I was growing up, the guys who were playing music were going along with the system – and they had to. I’m not blaming them for that. It was hard enough trying to get a job for anybody. So they were working – and at least they were recognized for the great artists that they were. People like Coleman Hawkins and Count Basie, and of course Duke Ellington, were subject to a lot of prejudice, but they were able to maintain a certain level of dignity. That’s what we younger people wanted – and a little bit more dignity. But there weren’t a lot of role models. Charlie Parker was one of the guys we followed. Even the great Dizzy Gillespie – a wonderful artist and innovator – liked to clown around and joke. Charlie Parker didn’t like that. He thought it was too much like being a showman or minstrel. Therefore, Charlie Parker became our prophet. He became the one we wanted to emulate, not only musically but in his actions. He represented a dignity about the music, and that’s what we wanted to do.

iRJ: Was there any division between those who wanted to be taken seriously and those who felt they could still have fun at it? Was there a lot of in-fighting between the two?

SR: No, there was not, because everybody – whether they acted like they went along with the accepted norms or not – wanted to have that dignity. It’s like with slavery, if you see a film like Gone with the Wind, you might come away thinking slaves were happy. No, slaves weren’t happy. Nobody wants to be a slave. Musicians didn’t want to be looked at as minstrels. They wanted to be recognized for the great artists they were. There was no bifurcation between artists who were accepting of the status quo and those guys like us who wanted to get more dignity and respect. Everybody felt the same way. It was just that some of the younger people wanted to fight. That’s why they don’t send old people to war. They send young people to war, because the young people are gung-ho. There was no real philosophical difference, and the only fighting that was going on was between guys who didn’t like bebop or Dixieland music. Even that was overplayed in the press, because Louis Armstrong knew that Dizzy Gillespie could play – and Dizzy Gillespie certainly knew that Louis Armstrong was great.

iRJ: What was the turning point in getting respect for jazz musicians?

SR: Well, I look at the bebop era, because – being led by Charlie Parker – the bebop musicians were much cooler. When they played, the minstrel thing was farther away from them. All they did was play at a super high level that everybody had to admire. That came when bebop began being recognized for what it was.

iRJ: People used to joke about how Thelonious Monk was different. How did you feel about him?

SR: I was closer to Monk than the people on the street. People talked about Monk. That didn’t resonate with me. Monk was an idol. Young musicians were looking up to Monk, so people on the street talking didn’t have any effect on me. We all had our little things. But, I was practicing with Monk and his band when I was in high school. I knew Thelonious and Nellie before Toot and Boo Boo were even born. People try to make Monk out as some kind of weirdo. It’s stupid! But maybe that helped people come to see him play. You can’t waste too much time worrying about what people think when you’re doing something you know is right. Monk didn’t have time to worry about what people thought because he was music 150 percent.

iRJ: You were a part of the Great Day in Harlem image. How did you get invited to become a part of that shoot?

iRJ: You were a part of the Great Day in Harlem image. How did you get invited to become a part of that shoot?

SR: Art Kane called me and said, “We’re doing a picture of a lot of jazz people in New York City, and we’d like you to be included.” Well, this was a big deal. Kane was with Esquire, a very popular magazine. To be invited to be portrayed with all of these really great musicians – these were my idols, my giants – was a big deal. By the way, I was the youngest guy in that picture. It was an honor for me to be there. Evidently, it turned out that it was an honor for a lot of those other guys to be there, because you see how many people showed up. The only guys who weren’t there were the ones working out of town, like Miles [Davis] , [John] Coltrane and Paul Chambers. Their bands were working more, I think, than a lot of other people. As usual, those were slim times for jazz. It always is. Most of the musicians in New York were there and it showed. They all were proud to be jazz musicians, and proud to have the opportunity to be involved in the picture, which showed a certain community, and sense of camaraderie, among us. A lot of these guys I didn’t know. I knew of them, like the pianist Luckey Roberts and the great Stuff Smith, the violinist. Maxine Sullivan, the great vocalist, and Mary Lou Williams – and the lady who just died, Marian McPartland – were in that picture. I knew Monk, of course. I knew Art Blakey, Charles Mingus, and Coleman Hawkins. But I didn’t know Count Basie, and I might have met Lester Young by then. I got to know them later. Many of them were older musicians, from an era before mine. It was great to be there with them. There’s not many of us left now. Benny Golson and me, and I think Horace Silver, are all that are left from that day, now that Marian McPartland has passed away.

iRJ: We had Bird, then Miles and Coltrane, leading the bebop era. What happened to music after that? In 1959, we moved into [Dave] Brubeck and Miles’s Kind of Blue and Charles Mingus, and things were changing. What was happening in that period?

iRJ: We had Bird, then Miles and Coltrane, leading the bebop era. What happened to music after that? In 1959, we moved into [Dave] Brubeck and Miles’s Kind of Blue and Charles Mingus, and things were changing. What was happening in that period?

SR: With any art form, there are ebbs and tides. People refer to that picture as representing the Golden Age of jazz, and I think that’s correct. There were people from an earlier generation alongside people from a later generation. Many great people were around at that time. In 1959, like you said, these guys started changing the music. Coltrane got his group together in the early Sixties, and they cooked until about 1967. After that, there aren’t that many great people. I don’t want to forget Ornette Coleman. He was out in California. He wasn’t in New York, or he might have been in that picture. But he wasn’t around in those years. Ornette Coleman made a big contribution in those years to jazz music. But there was a drop-off. Everything doesn’t stay on that level with so many great people. There’s been a little drop-off since then. Jazz has had to sort of compete with world music and this and that – strange and different forms of music and people’s ability to listen to different things. So jazz has been in a bit of a slump. But jazz will always be here. Right now, a lot of people are complaining that they can’t get work. But that’ll change. What goes down must come up, and that’s the way it is.

Then you’ve got the changes in the record industry, and you’ve got these record companies going out of business. So the artists can’t get recording contracts, and people are getting jazz music for free on all of these downloading services. It’s just a change in time. But I certainly believe that it will regenerate, because jazz is just the greatest music there is. People all over the world like jazz, and there’s something about seeing guys playing jazz that can’t be duplicated. So I’m not worried about jazz. I’m worried about the musicians who can’t get paid a lot of money like they deserve, but the music will remain. It will always be here.

iRJ: Regarding your time on the bridge, how did you decide to go play there and what was going through your mind as you played while cars passed?

SR: It was great! It was like getting out of the city. When you play any instrument that makes any sort of sound and you’re living in a New York City apartment, you’re going to have people say, “Hey, man! I want to sleep. I don’t want to hear you practicing.” It’s very hard for people who play musical instruments to be able to survive in the city with all of these people living next door to each other. That was a problem for everybody. It was a problem for me, and it’s a problem for any musician living in New York.

I happened to be out one day, walking around my neighborhood. I looked up at the steps on the bridge, and I said, “Gee, let me walk up there.” When I went up there, I said “Wow!” It was empty. There was nobody walking across the bridge. I started walking across to Brooklyn, and there was one or two people coming the other way. I realized, “Wow, I can come up here with my horn and practice.” It was like a great gift that was bestowed upon me. So I took my horn up there the first time, and I found a spot where nobody could see me – just a few people walking across the bridge. But the trains couldn’t see me, and the cars couldn’t see me. I was looking over the river, and the boats were coming down the river. I’d blow my horn to the boats. But I was completely able to practice without anybody seeing me. I even went up there at night sometimes. In those days, you could do that in New York. Nobody was going to hit you over the head and steal your horn. It was okay; nobody could hear me.

iRJ: When you got out of Rykers Island, you were homeless for a while, right?

SR: When I came out of Rykers Island, I had a home in New York City because my family lived here. I always had a home here, even though I had alienated my family. But when I was in Chicago, I didn’t have a family. I had other people’s families that were very nice to me. It was like I got a new family. I met some really beautiful people in Chicago. Living in Chicago was one of the most wonderful experiences of my life.

I first came to Chicago in 1948, and I lived on 47th Street at the South Central Hotel. Then I lived with some people around 69th Street. I lived at the YMCA on 35th Street for a while. It was a famous YMCA where a lot of Pullman porters stayed, and it had a lot of social activities. In fact, I used to practice there with this great trumpet player that passed on. He didn’t stay with us too long.

When I first came to Chicago, I was “carrying the stick.” That’s what we used to call being homeless at that time. Hoboes used to carry a stick, and they’d have a bag tied on each end with their belongings. That was how they used to do it. Now, I guess they roll it around in a supermarket cart. So I was carrying the stick, you know – sleeping in parked cars, in the subway, any place.

I got myself straight at the Lexington – a place for rehabilitation in Kentucky – which was not like a prison. Drug addicts were treated like sick people there. Then I came back to Chicago and lived in all of these various places.

Getting off of drugs in 1955 was a big turning point for me, and then moving to Chicago was when I really turned my life around.

Words by Grant Mabie