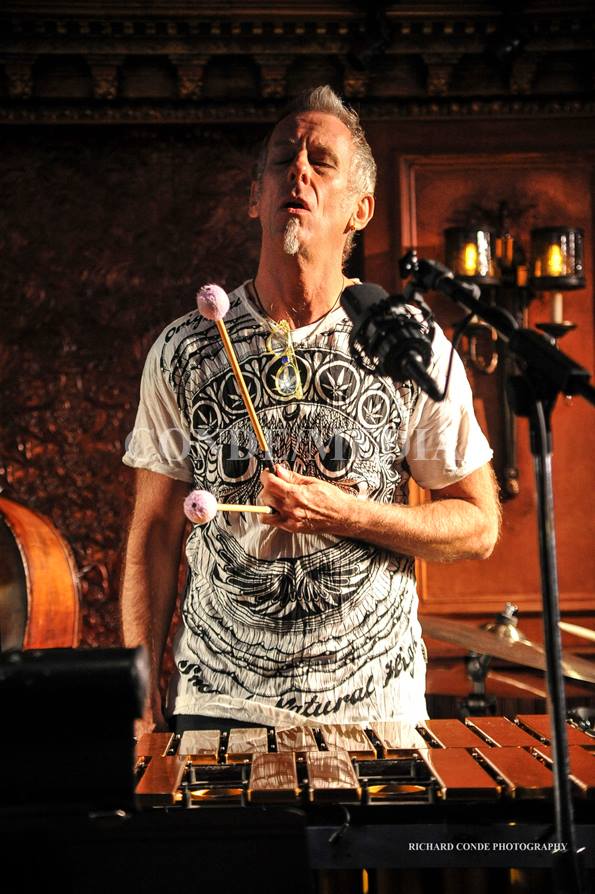

Joe Locke is an award-winning vibraphone player who has played with a Who’s Who of jazz legends both past and contemporary, including Dizzy Gillespie, Pepper Adams, Mongo Santamaria, Grover Washington Jr., Dianne Reeves, Ron Carter, Randy Brecker, and many more. His varied tastes have also led him to sessions or gigs with Rod Stewart, the Beastie Boys, the Moscow Chamber Orchestra, and Cecil Taylor. His latest album is 2013’s Lay Down My Heart: Blues and Ballads Vol. 1. iRock Jazz recently sat with Locke to ask him about the process of being a self-taught musician, his experiences and memories, and his view on the role of jazz today.

iRJ: Is there an advantage or disadvantage to being a self-taught musician?

JL: That’s a great question, man. I studied piano and classical percussion – but very peripherally – when I was a boy and learned how to read music by taking piano lessons. But when I got into jazz I took lessons at the Hochstein School of Music in Rochester, New York, where I grew up. And I studied with some older musicians who really knew their game, and the most important thing I got from them was sort of how to teach myself – how to listen to records and transcribe what great musicians were playing. If there was a particular phrase that attracted me, how to transcribe it, to analyze it, and then how to play it on my instrument. That was really vital to my education.

And there aren’t a lot of vibe players, so on the vibraphone I’m a self-taught player. I would listen to piano players, trumpet players, guitar players, saxophone players who I dug and then I would figure out how do I take that and put it onto the vibraphone? So, for me it was really a process of taking a little from here, a little from there, and the technique I have today came from the struggle of trying to get to be able to play that language on this instrument. And I think it was a good thing I was self-taught, because it really helped me to find my own voice. It was the way I went about it, and anyway it was the only way I knew to go about it. So, for better or worse, that’s been my journey.

iRJ: When you listened to these records, and you were kind of diagnosing what you heard and transcribing that, what was that process? What is that creative process like?

JL: Music is all about feelings, and it’s all about when someone plays something that it makes the listener feel some kind of way. There should be some kind of visceral, emotional response to what that person is playing. If you listen to Lee Morgan play the trumpet, for example, you hear a personality and you hear an attitude or something that resonates emotionally. And, for me, I would hear a phrase and I would go, “Oh, I just want to know that. I want to know what it feels like to play that phrase on my instrument.” So, for me, it was just a process of learning the basics of a tune – its harmonic structure or what the chord changes were – and then saying, “Okay, so how did Lee negotiate those changes? How did he play those chords, and why do I like it so much? Let me figure that out.” It was about hearing something I loved that made me feel a certain way, that gave me joy and excited me, and then trying to figure out how they got to it.

So I just use my ears, man. One trains the ears to understand what intervals are being played, and you listen to the record and you listen to it again and again until you get the notes right. Then, when you play it back on your instrument, you’re playing what the guy on the record was playing. It’s as simple as that.

Plus, I had the advantage, from the time I was about 15, that I was gigging. I was playing with much older musicians, an organ trio of some very experienced cats. I’d be able to go on the bandstand with a great jazz group and get my ass kicked and try to apply that stuff that I was working on. It was very much an apprenticeship kind of a process: hearing something I loved, why do I love this, analyzing it, and then saying, “How do I play that on my instrument?” And, to be honest with you, that process is still going on.

iRJ: Moving to your time when you were playing with Dizzy Gillespie, how did you get that gig, and what was it like, and what did you learn?

iRJ: Moving to your time when you were playing with Dizzy Gillespie, how did you get that gig, and what was it like, and what did you learn?

JL: I didn’t play in Dizzy’s band. I was playing in a band of a saxophonist named John “Spider” Martin, who was a wonderful tenor player who came from the Niagara Falls area. I was in Spider’s band right out of high school. Dizzy had a close friendship with Spider, and so Dizzy actually played with Spider’s group. And we did several concerts, even a tour of Florida, with Dizzy and Pepper Adams in Spider’s band.

So Dizzy was actually a guest with Spider’s group. But it’s strange looking back on being a 17 year old and getting such a good amount of hang time with Dizzy Gillespie, sitting at the piano with him and having him talk to me about chords and showing me chord voicings and chord changes. It was invaluable. And just being able to have that time on the road, whether it was being in the car, travelling with him – like I remember a trip we took from Miami to Naples, Florida, going through Alligator Alley – and him just telling stories or sitting at the piano with him at a soundcheck and him telling me, “Young man, it’s all about chords.” And I had no idea what he was talking about.

But, many years hence, the lessons that he taught, just through his conversation, are being revealed even today. So it was an absolutely stunning and rare experience, to be able to have that kind of hang time with him. And I thank Spider for that very, very much. Although Spider has passed on, he was the catalyst that enabled me to even be able to get in the orbit of Dizzy Gillespie for those many concerts we did together. That was really beautiful!

iRJ: How difficult is it moving from jazz into different genres of music played by artists like Rod Stewart or the Beastie Boys and weave into those bands and that music?

JL: I played on a track on one of Rod Stewart’s standards records. And isn’t it funny that Rod Stewart, who is a rock cat, is dipping into the Great American Songbook, which is what jazz musicians are familiar with? And when I did the Hello Nasty album with the Beastie Boys, I got the call and of course I was thrilled to get a chance to work with the Beasties. When I walked into the studio, I said, “What are you looking for?” and they said, “Well, we’re looking for like a Cal Tjader vibe, a Soul Sauce kind of vibe.” They were very knowledgeable about jazz and really wanted it authentic. They were listening to Stan Getz Au Go-Go, they were listening to Cal Tjader’s Jazz at the Blackhawk, and they were really into the music. So you’ve got cats like the Beasties knowing what’s going on in the jazz world, and Rod Stewart and Clive Davis are dealing with the Great American Songbook, so it’s not such a genre-jumping thing. They’re dipping their toes into that same pool.

I did a track or two with Randy Brecker on his Hangin’ in the City album, and Randy Brecker is a guy who is comfortable playing rock, playing funk, as he is playing straight-ahead jazz. I think anybody of my generation or after grew up with the Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire, listening to Led Zeppelin as much as I did Charlie Parker and John Coltrane. So the genre-jumping isn’t really a big thing. And today my young friends, who are a product of hip-hop as much as they are of jazz, are mixing it up. You know, the genre stuff isn’t really an issue. I think sometimes there are forces that would like to make it an issue and would like artists to be one thing or the other. But for many of us it’s hard to be just one thing, because we love it all.

The Joe Locke Group (feat. vocalist Kenny Washington) from nadworks on Vimeo.

iRJ: Harmonica tends to be rooted in the blues. Do you think the vibraphone is rooted in jazz?

JL: Definitely jazz. You know, the vibraphone was only invented around 1920. It’s a very young instrument still. It’s amazing to think that the vibes isn’t even 100 years old. But a really interesting the about the vibes is that, when you tell people it’s what you play, many don’t know what it is. But many people have heard the vibes. They just don’t know that it’s the vibes. When you listen to film scores, you’ll often hear the vibes. And it’s in TV commercials. I’ve done a bunch of TV commercials. And Motown and the Philly sound, everything from Smokey Robinson to Blue Magic, have the vibes in there. It’s even in pop music. There’s an Eric Clapton record called Journeyman that’s got vibes on it. And k. d. lang. Even the Rolling Stones. One of their most famous records, Sticky Fingers, has vibes on it. There’s a Hendrix track called Driftin’ that Buzzy Linhart plays vibes on. So it’s really interesting that the instrument is still largely unknown in our culture and I still have to explain what it is when I tell people what I play. People do hear it; they just can’t identify it as such.

iRJ: Tell us about your latest album, and how was creating it different from other work you’ve done?

JL: The whole idea of this record was to make an album that was simple and direct. I was telling you about my days in an organ trio back in Rochester, New York. This album actually takes me back to those roots. I remember when I was much younger, playing in clubs where the music was part and parcel of the social fabric. The music was very artistic and on a high level, but it was also part of the party that was going on. What was happening socially in the club and what was happening in the music were sort of two sides of the same coin. They were kind of flowing together with this wonderful ease. And I found that very attractive.

When I grew up, jazz was on the streets and in the clubs, and I remember the feeling of sharing this music with the listeners. The music was killin’ and it was great, but it wasn’t so complicated that folks coming in just to have a good time couldn’t understand it. So I wanted to go back to those roots, making a record that was musically valid but that had a simplicity to it that folks who maybe had just worked a really tough week in their jobs could come home, put that music on, and kind of get fed by it in a soulful way. And that’s what the record is.

iRJ: How have you stayed relevant with an instrument that’s still relatively new but trying always to move forward artistically?

JL: That’s very easy. I’m still very much a student of the music, and I’m always going back to the history of the music. I’ve been listening to Art Tatum lately, listening to Art again for the umpteenth time, and I’m listening to what the young cats are doing now—in rock, in jazz, in classical music—and getting inspired by what they’re doing. If I hear something and I don’t know what it is, I want to figure it out. And, whether I put it into my own music or not, I want to stay a student. Hopefully, I can do that for as long as I’m in the game. I think it’s just a matter of not being intimidated by the new, but learning from it and continuing to be inspired and excited about what’s happening now. That’s really what it’s about for me. I still like to consider that what I’m doing is valid in the present moment. I never thought jazz should be a museum piece or should be honoring the past. It should be honoring the present and looking to the future as well.

Joe Locke will be performing at the Cape May ExitO Jazz Festival, Saturday, November 9th.

Words by Grant Mabie