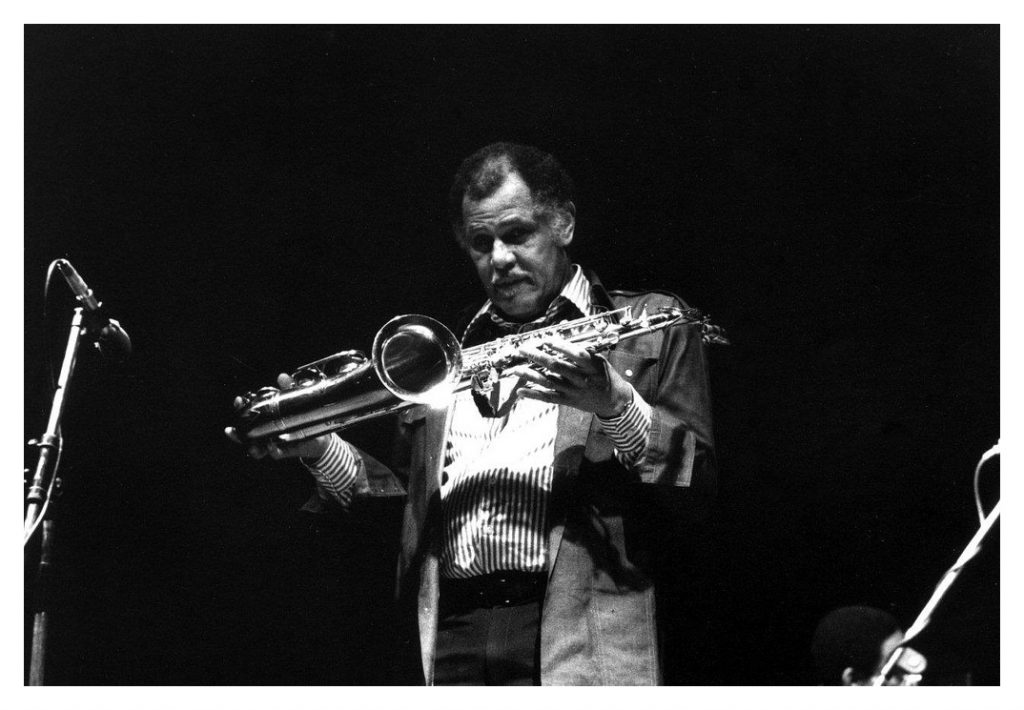

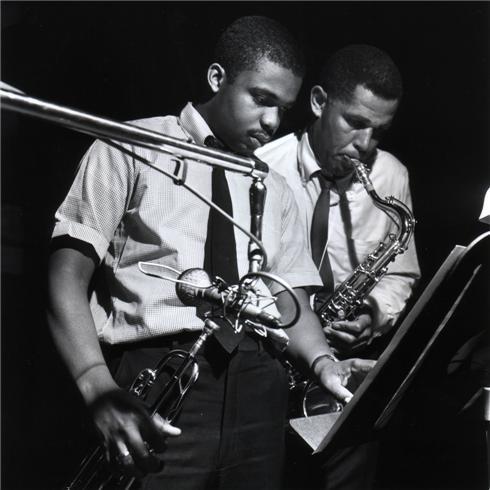

Dexter Gordon was one of the most definitive voices of the bebop movement. Ranging from John Coltrane to Jackie McLean, Gordon sketched the stylistic framework for countless artists. As it often goes with jazz, he himself was a by-product of his musical predecessors—more specifically, Lester Young. Resulting from that exposure, he presented a sound which was so rich it only made sense that it was birthed from an unrelenting 6’6” frame.

Gordon was a native of Los Angeles, but like most other artists, his career began to take even greater shape while living in New York City. However, this story does take a divergent trip through Europe. For fourteen years, Gordon made his home overseas. Living there is where he met his future wife, Maxine Gordon.

As time went on, Gordon found himself living back in the United States – not only with a resurgence in his career, but also with an Academy Award nomination looming for Best Actor for his leading role in the 1980 film ‘Round Midnight. Although Dexter Gordon since has passed, his wife Maxine lives on and continues to remind us about one of the most intriguing lives in the history of jazz.

Recently, iRock Jazz sat down with Maxine Gordon to talk about the travels, and triumphs of the late, great Dexter Gordon.

iRJ: Tell us a bit about yourself. Where were you born? How did you first meet Dexter?

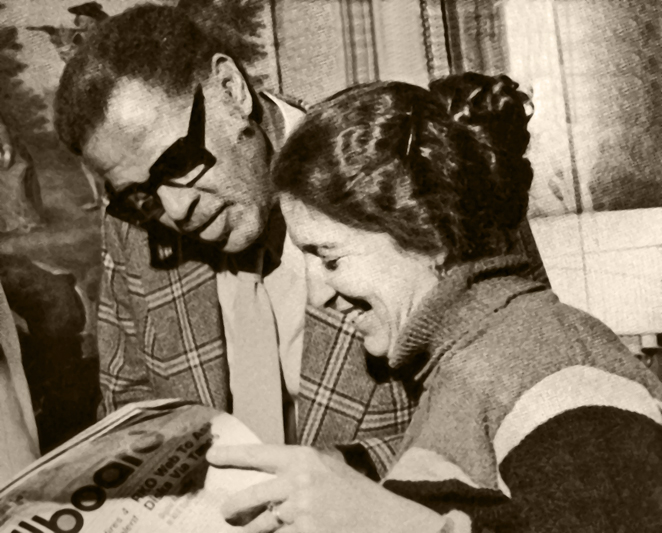

MG: I was born on 102nd and West End, which doesn’t mean anything to people in Chicago. But if you’re from New York, then you know a lot about someone when you say where you were born. I’m an old jazz fan. We started when we were teenagers, going to clubs. When I was 15, I think I just wanted to try and find a way to be around the music, and the musicians. But I actually met Dexter in 1975 in Europe. I was working as the road manager for an agent that did the big festivals, and had groups touring. Dexter’s group was stranded in France because there was a train strike. And so they sent me. And as we always say, the rest is history.

iRJ: When you were in France, and you first met, what was the relationship like? How did it start?

iRJ: When you were in France, and you first met, what was the relationship like? How did it start?

MG: Well, when I first met Dexter, and heard the group, I was stunned. He had been away quite awhile in Europe, and he was quite a bit older than me. And so I knew who he was, but I had never heard him in person before…I had only [had] heard him on record. So, when I heard him in person, I was like, ‘Oh, my goodness. This guy is fabulous!’ And we started having a friendship, and then he started talking about coming back to the states. So, I was like, “Well, how hard could that be?” And he was like, “I don’t think it’s as easy as you think, because I’ve been gone a long time and there doesn’t seem to be much interest in bebop.” I was like, ‘Well, you could try’. So I called Max Gordon [owner of the Village Vanguard]. I had known him since I was a teen. So, I said, “Max, I’m in Europe and I heard Dexter Gordon, and he sounds great. He wants to come back. Can you give them a gig?” And he said, “No. I don’t want to give him a gig. Nobody will come. He’s been gone too long. They’ve forgotten him’. And I was like, “No, Max I’m telling you he really sounds good!” So, then I said, “If you don’t give him a gig I’ll never speak to you again.” And he was like, “I don’t care if you never speak to me again” and he hung up on me. That was the beginning of my career in management [laughs]. So, then I called him back the next day and I was like, “Okay, so, what would it take to book Dexter at the Vanguard?” And he said, ”Well, I’ll give him a gig but, I’m not giving him a guarantee,” which means that Dex would have to pay the band if nobody came. So, I told Dexter, and he said, ”Ok. Let’s try it.”. Now, the rest is history because it was a huge success, and Dexter got a contract with Columbia Records.

iRJ: Leaving the United States during that period of time, especially during the Civil Rights Movement, how was he treated differently in Europe?

iRJ: Leaving the United States during that period of time, especially during the Civil Rights Movement, how was he treated differently in Europe?

MG: The main difference was that he worked all the time. When he left the states, he couldn’t get any work. There wasn’t any interest in bebop or the music he played. It was a very difficult period for him after the 50s. It started with one gig at Ronnie Scott’s club in London. He had a two-week gig, and when he got there, they started offering him things: could he come to Copenhagen; could he come to Paris; could he go to Spain. So, the difference was that he worked all the time. He played his music. Nobody told him what to play; what to record. He was still recording for Blue Note. So, they would be able to come to Paris to record or he would come back and record. So, he was aware of what was happening in the States. He moved to Copenhagen. There, he was in a circle of what they called expatriates. He was one of the six Black Panthers in Copenhagen. I guess you didn’t know they had a branch in Copenhagen [laughs].

iRJ: How did Dexter get his first film role?

MG: [laughs] Well, you know he was in prison when they came to make the movie, Unchained. Now, he’s not on the soundtrack because “when you went to jail at that time, you were put out of the union.” So, he and Hadley Caliman were in it because they were in Chino. Chino was an experimental prison. It included group therapy and drug rehab, and the movie is about that prison. So, he was actually there. That’s why he’s in it. I don’t know if I’d consider that [to be] his first role [laughs], but it wasn’t his first acting role.

iRJ: Why was he in prison?

iRJ: Why was he in prison?

MG: For drugs. In California, using heroin was a crime. If they stopped you, and you were high, it was 90 days. If you were a repeat offender, they sent you away. Dexter was lucky. In 1960, he was able to be on parole. And then he was able to get a passport. And, so the minute he was off parole, he left the country. He said that if he had stayed here, “he would be dead.” So, the minute he had the passport, and got the offer from Ronnie Scott, he was out of here. He didn’t intend to stay for 14 years, but if you look through his recording history, there’s very little in the 50s because he was harassed so much by the police—sent away; let out; sent away; let out. He was lucky in a way because he got out of it.

iRJ: For his role in ‘Round Midnight, Dexter was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. Did that change him at all?

MG: It didn’t change him at all [laughs]. He believed he would be nominated. He was ready with his acceptance speech. So, I assume he did believe that he was going to win. When he was making the movie, Martin Scorsese said to me, “Maxine pack your bags. You’re going to the Oscars. This is the kind of part that gets nominated. It’s like Raging Bull. They won’t be able to use any scene that Dexter’s not in.” So, you know he told Dexter, and of course, Dexter believed it. And he kept saying, “Well, you better get ready because we’re going to the Oscars.” I was like ”Dexter, we’re not going to the Oscars. How can they nominate you? You’re a saxophone player. It’s your first major movie [role]. You’re black. Look who gets nominated.” But, of course, he was right, and I was wrong. He had already ordered a tuxedo, and I had to get on the telephone order my dress. And, so we went from Mexico to Hollywood for the Oscars. He wasn’t surprised. He wasn’t disappointed. He was the same person that he always was, even after.

iRJ: When Dexter came back from Europe, how was received by the other musicians?

MG: The funny thing about musicians is that they have a different sense of time. When he came back, he saw Art Blakey; he saw [Thelonious] Monk; he saw everybody. And they were all like, “Where you been? Good to have you back, Dexter.” There was absolutely no break in the 14 years he was gone. But you have to remember that the bands traveled. So, even though he was in Europe, they would come to Copenhagen, and he would get to see people. So, when he came back, they were like, “Oh good. Are you staying or are you going back?” Relationships amongst musicians don’t really have to do with geography or time, you know? They have a different way of relating to each [other].

iRJ: In the last stages of his life, what was the relationship like between the two of you?

MG: When they first said he had cancer, he was like, “Don’t worry about it. I’m not going anywhere. You might go before me.” Eventually, what he did was put a lot of things in order. He worked on the book, and asked me to finish it. So, about a third of the book will be in his words; in his writing. He asked me to put his music together, and he wanted me to finish college. He left instructions – these instructions. He was like, “If anyone really knows me; they won’t be crying. I had a great life.” So, he was quite philosophical at the end he was like, “The fact that I lived past 35 is a miracle in itself.” For musicians, it’s a tough life.

iRJ: Moving on to you and the foundation, how difficult is it to maintain the foundation and his legacy?

iRJ: Moving on to you and the foundation, how difficult is it to maintain the foundation and his legacy?

MG: Well, it would be a lot more difficult without my son Woody Gordon Shaw III. He runs the website, and the Facebook page. He is the director of the Dexter Gordon Society. That’s our nonprofit [organization]. I’m very fortunate to have him because I can stay in my lane, which is to finish the book, and to do my research. But the screenings—me coming to Chicago and introducing the film, and answering questions—that’s something I’ve been doing all year for the 90th birthday of Dexter. There’s renewed interest in the film and Dexter.

Through her eyes, we see Dexter Gordon. Yes. He was a wholly significant player within the canon of jazz. But he was much more than that. He was a man who lived an extraordinary life, and took seemingly every road less traveled. Few can lay claim to having done what he did on the stage. And even less can lay claim to what he did off of it. A renaissance man in every sense of the word is what he was, and his story is worth telling. And for that we have his wife to thank. It was under her guise that much of this story about his life became developed. And as she passes it on to the next generation of followers, and fans, we are “made all the better” for knowing the story of Dexter Gordon.

Words by Paul Pennington