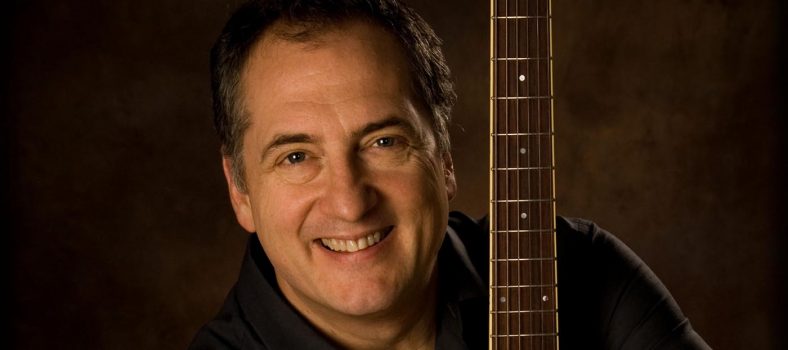

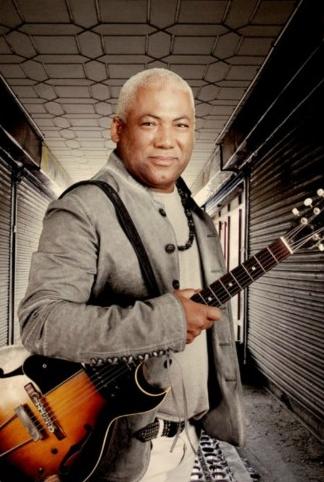

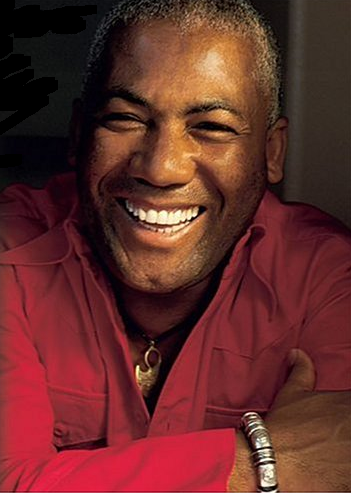

Jonathan Butler has toured the globe and given his audiences what they have come to expect. As a renowned guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter, Butler discovered his gift of music at an early age. By the age of seven he began playing the guitar and later performed with a group of other children that traveled throughout South Africa. It was then Butler saw the segregation and troubles of his country. This was his first glimpse to what we now know as Apartheid. He was the first black artist to be played on South African radio stations. In 1974, Butler recorded “Please Stay” and won a Sarie Award, which is equivalent to the Grammy-Award. He has shared the staged with Kirk Whalum, Ruby Turner, Dave Koz, Rachelle Ferrell, and George Duke along with many others. iRock Jazz had the pleasure of talking with Jonathan Butler about his music, his faith, and his country; South Africa.

iRJ: What was it like to grow up in Cape Town during a time when people were fighting for equality?

JB: Growing up in South Africa or growing up anywhere in the world as a kid, whether you grow up in the ghetto or the mountain top, for a kid, life can be normal and until you grow up that you become more aware and more educated about your social structure and what the communities are about and what the country really stands for. I don’t think any of us were really politically minded growing up as kids. As kids we just did normal things; played soccer every day, listened to music. You know struggles continued. It’s not just Apartheid struggles. It’s also people living in poverty struggling just to eat. When you don’t have education and you don’t have money and you don’t have the resources what you tend to do is survive, and most of us survived. Those of us who were able to leave and become educated became more aware of what the country stood for and was about. We got involved in music and we traveled. We saw the differences between the black and white, the colored and the Indians and how all these different communities had different laws and regulations. That’s when you kind of wake up to what it’s about. We were kids; we listened to music and we loved music. We did a lot of stuff in the community with music. You know, concerts, cabarets, carnivals, and later on we became more aware of what Apartheid really was.

iRJ: Do you consider yourself a jazz musician or a world musician?

iRJ: Do you consider yourself a jazz musician or a world musician?

JB: I’m a world musician. I’m not a jazz musician. I love jazz and I love all kinds of music and it really brings me back to world music. I’m a child of the universe. I grew up listening to everything and anything. As long as the music has spirit and African music has great spirit, jazz has great spirit, gospel music has great spirit.

iRJ: How do you learn the music and culture of jazz when from another country?

JB: When somebody’s born with a gift it’s about finding the tools. I didn’t grow up in a family were we had a lot of instruments around the house. My brother did have a guitar so I learned to play on his guitar. Singing was something that was just natural. I grew up singing at home. Wherever I could find an outlet or friends who had instruments I would go there hang out with them, use their stuff until I could afford to get my own. Most of the guys I knew growing up couldn’t really afford their own instruments. Everybody used each other’s instruments. Those who could afford it were a little different from the community I grew up in. Most South African musicians don’t come from Berklee or Julliard School. We come from the earth, we teach one another. Our music has definite roots. It has a definite root, harmony and rhythm. We tend to start there and then we sort of branch out American, Brazilian, and even British pop music. Pop music comes and goes because it’s all about fashion and trends. Jazz was never a trend and neither was gospel. Tribal folk music was never a trend; it was a daily conversation.

iRJ: How risky is it, as an artist, if you make records that stand for political or social issues?

JB: There are some records you’re going to make that’s going to have commercial value and some records you make are going to have personal value. Sometimes you just have to stand for what you believe is right. Not every record you make is going to sell a million copies, but it’s still a part of your life story. Every record is like writing a book; a different page in your book. Each page will represent a time, a season of your life and how you view the world. If you’re willing to make that statement and not compromise your artistic and musical integrity or your personal integrity – because not everything you do is going to sell ten million records. Your music is your tool, it’s your foundation. It’s your stage from which you speak and good are the artists who do that, but it doesn’t mean you do it all your life. You do it because you know it’s right. That’s all that matters, doing what’s right.

iRJ: How difficult was it to for you to assimilate with the musicians in this country before you received a major break?

JB: It’s very difficult because musicians here are very educated. They’re very knowledgeable so their theoretical background and their fundamental background in music is in the books as well. I don’t come from the books. I’m a self-taught person. It’s a different way and it can be intimidating. I grew up in front of all these musicians since I got here in the 80s. I just keep growing and the discipline is what I needed and the structure, learning composition arrangement, producing, performing; I learned all of those things. Which, now, is so useful for me to teach others such as my kids, who I involve in music as well.

iRJ: Nelson Mandela is in our thoughts at this time. Tell us what was it like to have met him?

iRJ: Nelson Mandela is in our thoughts at this time. Tell us what was it like to have met him?

JB: I was honored, fortunate and blessed to have met him. To have sung for him, to have been born in a country that had such great leaders: Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo, and Steve Biko. I was born in a country with great men and great pillars. These guys have meant so much to the nation. Not only is it personal to me meeting Nelson Mandela, but to know the man for what he stood for and what his calling was. He stayed the course no matter what. It’s an awesome story, faith, and strength that we all get from Nelson Mandela and all the great leaders that stood against Apartheid, fought against it, stood for justice and righteousness. I will always look at people like Desmond Tutu as a peacemaker. Nelson Mandela is a man who sought out the righteous. He was fighting for people’s rights and justice. He is just a pillar and a light in the world. He is a big light in the world. I am deeply honored to have met him and just be able to hug him and to say thank you and I love him and to hear him say the very words back to me was an incredible thing.

iRJ: What comes to mind when you hear the names of other renewed musicians from Africa, such as Hugh Masekela, Fela, and Sade?

Hugh Masekela is great. He’s one of the legends of South African music, definitely. Fela, he’s a legend of the West and North African music. A voice, that echoed and herald the African spirit and music that the world embraced because of Fela and Hugh Masekela. I don’t know much about Sade. She’s more European, neo sophisticated soul, but she’s just an awesome, beautiful deliverer of song.

iRJ: Tell me about your new music and your faith?

JB: I’m following my calling in life. My calling is much greater than just me being an R&B singer, a jazz guitarist, or a contemporary jazz guitarist. My calling is much greater and jazz was the platform that I have that God has given to me to proclaim music; gospel or Christian, and that’s what I’m really about. I’m definitely a spiritual person and I have a very deep relationship with the Lord. I’m following a deeper calling a deeper calling that I have in my life.

iRJ: You have embraced your African heritage and now you are embracing your spirituality. What were the turning points in your life that have placed you on this path?

JB: Well this happened thirty years ago. I became a Christian thirty years ago and part of my journey is evolving. It’s evolution, its reinvention, recreation of the very same person that I am on the exterior. That’s what I’ve been doing, following my own calling.

iRJ: Tell us about your new music?

JB: I’ve got a Christmas record that’s coming out its going to be awesome. The new album I’m doing is very much really an old school, organic, classic Jonathan Butler – R&B, jazz, it’s soul, it’s flavored. Soulful, R&B, jazz with the spirit of gospel all over it.

I’d like to mention my safari that I do every year; October 22nd. People can go to my website, www.jbutlersafari.com. I take people to Africa – 30 or 40 people and show them the country. It’s real life changing, real eye opening, very educational and it’s one of my great passions to take people from here to South Africa.

By Shonna Hillard