Ray Charles. Miles Davis. Duke Ellington. Donna Summer. Michael Jackson. George Benson. Chaka Khan. Frank Sinatra. Lena Horne. These are some of the greatest, most famous recording artists of the 20th century, all of them linked by a common component: Quincy Delight Jones, Jr. The legendary impresario (calling him a musician/arranger/conductor/composer/producer/mentor/media mogul would be as longwinded as it is accurate) has worked with gods and goddess and on the biggest stages in the world from the Hollywood Bowl to Japan’s Budokan Arena. At age 80, Jones’ work ethic and influence are as strong as ever, but how does he do it? How on earth did this trumpet player from Chicago get gigs writing movie scores for Sidney Lumet, TV show themes like “Sanford & Son”, arranging albums for Count Basie, producing anthems like “We Are The World,” and carve diamonds-in-the-rough like The Brothers Johnson, Siedah Garrett and Tamia into bona fide hit-makers? “I don’t know,” Jones answered when asked by iRockJazz. “I can’t explain it, but I see it before they see it.” Psychic powers, maybe? Does his limousine come equipped with a flux capacitor in it, allowing him to travel in to the future? His perceived clairvoyance, when properly examined, is the product of open-mindedness, a sacred pursuit of knowledge and the willingness to help people be their best selves in the face of doubt and indifference amongst the masses.

Jones’ melodic sonar of an ear has now found another talented blip on the radar of the music world in the form of 11-year-old pianist Emily Bear. “Q” literally could have his choice of ready-for-the-world adult artists to groom, so why a pre-pubescent pianist? Actually, this is not without precedent. Jones’ penchant for finding talent has no age limit. Patti Austin, one of Q’s go-to-vocalists (“Razzamatazz,” “Baby, Come To Me”) was but a little three-year-old girl when “The Dude” saw her instantly memorizing vocal takes of her Queen of the Blues godmother Dinah Washington in the 1950s. Leslie Gore was all of 16 when Mercury Records gave her tapes to “Q” because they didn’t know what to do with her – resulting in the 1963 number one smash “It’s My Party.” When Tevin Campbell sang on Jones’ 1989 hit “Tomorrow (A Better You, Better Me),” he was only 12. Ergo, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Bear is his latest project. “She’s been a composer since she was, like, four years old,” Jones spoke of Bear. “I call her baby Mozart.” That’s a mighty grand assertion, but it just may be precise. The majority of her 2013 debut Diversity – produced by Jones – consists of songs she composed between six and 10 years of age, and all songs that are incredibly dynamic, emotive, vivid and accessible.

Quincy Jones (right) hanging with Dizzy Gillespie (center)

Quincy Jones (right) hanging with Dizzy Gillespie (center)

Diversity marks the second album in as many years that Jones produced a young, prodigious pianist. Last year, he and then 26-year-old Alfredo Rodriguez dropped Sounds of Space, a collection of songs that, Jones contends, are so amazing they’ll “make you smack your grandpapa!” Rodriguez was classically trained in his native Cuba and severely impressed Jones at the Montreaux Jazz Festival in 2007 with his uncanny ability to fuse various influences into a performance and composition style unlike anything being played today or yesterday. “I’ve never heard anything like that in my life before,” Jones gushed about Rodriguez. “He’ll outdo anybody on the planet, and I don’t care who it is. I’m not guessing. He practices 14 hours a day, orchestrates everything, you name it: jazz, salsa, anything. He’s a junkie. Nobody can touch him.” Having collaborated with the greatest pianists who ever lived, including Chick Corea, George Duke and Greg Phillanganes, it’s safe to conclude that Jones isn’t just talking up his protégé for exposure. Jones believes that Bear, Rodriguez and a host of other young, worldly musicians are the key to the future, as they share a unifying trait with those aforementioned greats of the past and present; “They do everything they’re supposed to do – they work hard and they feel hard, and [have] a strong will to work,” Jones explained. “They can revolutionize the dumbing down that’s been happening the last few years. They can take that quality right back up.”

To say that music today has been dumbed down would be a monolithic understatement. In this society of just-add-water stars with shows like “American Idol” and “X-Factor”, the population is still being force-fed singers who fit into the right marketing mold and portray the winning image that will ensure record sales. The irony is that it’s this vote-em-N-mold-em culture that’s contributing to the current free fall in music. “I’m more concerned about the record industry,” Jones revealed. “We have 98 percent piracy all over the world and that’s a problem.”

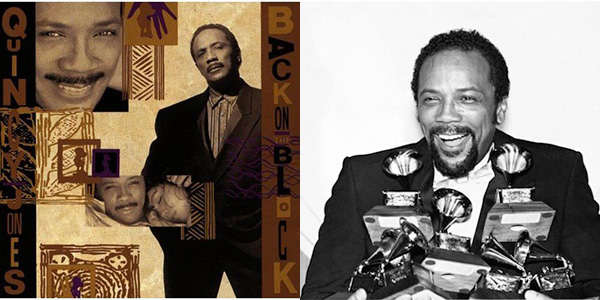

Quincy with Duke Ellington (left) and Donny Hathaway (right)

Quincy with Duke Ellington (left) and Donny Hathaway (right)

Perhaps one of the reasons illegal downloading occurs so profusely is because there isn’t much product with high enough quality to make people want to spend money on it. Jones has never been a believer in image-over-art. He’s proven so by exploiting talents in individuals that no one bothered to look for, not even the individuals themselves. Rapper Will Smith never would’ve become the lead in “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” had it not been for the persistent insistence of Jones, a seven time Academy Award nominee. It was Jones who convinced keyboardist James Ingram that his gruff singing voice would be an asset on career defining songs “Just Once,” “A Hundred Ways,” and “Yah Mo Be There.” Who else but “Q” could envision a Chicago talk show host in Oprah Winfrey as portraying Sophia in “The Color Purple”? When everyone else said no, “The Dude” said go. “There’s a power in being under estimated,” Jones stated. “People get out of your way when you get underestimated. When I did “The Color Purple”, people said ‘Steven Spielberg is a five million dollar a movie director. How is Quincy gonna get him to direct his first film’? But it happened.” When an artist has no expectations to follow, that’s when they often create their most free, honest, and best results (i.e. Jackson and Jones’ Off the Wall).

One of the ways Jones has managed to create expectation-free environments for himself and his collaborators has been consistently reacting to the writing on the wall. Take today’s emerging movement of jazz/hip-hop fusion that’s being spearheaded by musicians like Robert Glasper, José James and Chris Dave. Their albums, an antidote to traditional jazz, have garnered praise by the public and press as revolutionary when, in fact, Jones created the template for this movement decades before. His 1989 Back on the Block album won six Grammys for juxtaposing jazz heavyweights like Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody and Ella Fitzgerald with golden era MC’s Grandmaster Melle Mel, Ice-T, Kool Moe Dee and Big Daddy Kane. The seeds of this historical LP were sown by Jones in 1975 when enlisting spoken word pioneers The Watts Prophets for his album Mellow Madness’ “Beautiful Black Girl.” Jones contends that a lingering disconnect of heritage in America is contributing to music’s descent in quality and commerce. “They don’t even know when it started,” Jones spoke of hip-hop’s foundation. “I asked some very talented guys ‘What do you think is the beginning of rap’, they’d say ‘1971 with Gil Scott-Heron’. We were doing rap in Chicago in 1939. It comes from Africa; mbunge and the griots.”

Knowledge and respect of music’s true origins is just one of a series of components that have given Quincy Jones a telepathic sense of the future. The kind of crystal ball he operates doesn’t consist of cloud-like images of the yet to come, but a never-ending acquisition and application of technical smarts and historical wisdom. As he put it himself in his 2010 book “Q on Producing”, it’s all about finding the right balance of “soul and science.” “It’s mathematics,” Jones professed, “‘Cause music and mathematics are married, man; God married them. Coltrane had that every time. In fact, he got “Giant Steps” from an opening example of humming exertion. Every time I saw him, he did it, that’s why it sounds like it’s mechanical. When you read the binary and trinary numbers and you really know your sh**, you’ll see left brain, right brain, everything’s music in motion.” Jones will continue to see the music in motion as he molds future legends, therefore making his list of collaborators all the more uncanny and praiseworthy. “I’ve been around long enough to have worked with all of them [chuckles]; Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday at 14, grew up with Ray Charles. It’s been a blessing.”

By Matthew Allen