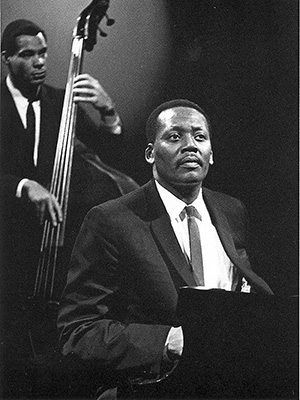

After contributing six decades of musical direction and genius, Randy Weston remains one of the world’s foremost pianists and composers today, a true innovator and visionary. Encompassing the vast rhythmic heritage of Africa, his global creations musically continue to inform and inspire.

Recently an iRock Jazz interviewer sat down with Randy Weston to discuss where he feels the source of Jazz music resides.

iRock Jazz: Who have been your greatest musical influences?

Randy Weston: The first would be Count Basie, because Count was a master of the Blues. He knew how to play a few notes and get a message across. It seems like it would be easy to do that, but it’s not. He had an incredible sound on the piano. My second influence was Nat King Cole. When I heard Nat play, I heard all that beauty. Each note was like a jewel. I’m sorry he started singing[laughing]. Although he was a great singer, he also was certainly a great pianist. He gave me that beauty in music. The third would be Art Tatum. I never tried to play like Art Tatum, but he’s the high master. He gave me that daring [and] imagination that you can do things in music that you don’t hear every day. The next one would be [Thelonious] Monk. When I heard Monk play, I heard the magic of ancient Africa in his music. When he played, I also heard the universe. You could never call Monk [merely] a Jazz musician. He was incredible. He put that magic in, and like all the giants that I mentioned, they were all masters of the blues.

iRJ: How do you feel that Jazz or African-American Classical Music has influenced your perception and philosophy of the music?

RW: When I first started playing this music, you had to do two things: You had to be able to play the blues; and you had to be able to play for a woman. These are the two requirements I learned from the elders. They meant that the woman represents the earth, represents our mothers and grandmothers. So, whatever you do in the music you have to have feeling. People have to feel something. This does not mean that it has to be just with your ears. The music has to touch your soul. The thing with the blues is that it’s African civilization in America. During my travels in Africa, I heard what we would call the origin of the blues. With no other music can you say ‘I love my baby, she doesn’t love me.’ We didn’t need a lot of words.

iRJ: Can you talk a little about the history of African music?

iRJ: Can you talk a little about the history of African music?

RW: African civilization goes back thousands of years, so the whole concept of music came out of Africa. When African people were taken away, or when they traveled [and] decided to go north, south, or west, they brought that music with them. The Moors brought the music into Spain. Also, the ancient Egyptians were the most fantastic with music. They had schools of music; they had incredible musical instruments, harps, string instruments [and] drums. When you go down the Nile and you look at the great Egyptian monuments, you see all the instruments that we use today. For me it’s incredible because the music of Africa describes the continent itself.

iRJ: How would you describe the music scene in the Sahara?

RW: The people of Africa, for example in the Sahara, produce a kind of music that describes how traditional people are in tune with nature. They know that music comes from the universe, so they use music as a healing force. If they have a harvest, they have music for harvest. If there’s a baby being born, there’s music for that. If there’s a funeral there is music for that. But all the music is equal and it’s for everybody.

iRJ: How would you suggest others learn about traditional jazz music?

RW: I talk to the students and I tell them ‘You do your research.’ I lived in Africa seven years, I traveled through eighteen African countries, looking for the oldest people I could find, trying to listen to the oldest music I could listen to. The traditional music of Africa is so complex, so organized. There are some societies that if you’re 5-years old, in order to become 6-[years old] you have to play the songs of a 6-year old. If you don’t learn those songs, you never become 6-[years old]. There are some societies in traditional Africa [where] you can have a funeral and not officially die until certain songs are sung at that particular funeral. So their whole concept of music is in touch with Mother Nature. I think that’s why our early Jazz was so fantastic.

Young people are so happy because I said ‘Look, if you love music you have to go back before western civilization. You have to go back to the east. You have to listen to the music of China, of India. You don’t have to decipher it, just put it on and do what you’re doing.’ Again, I can’t emphasize the importance of Mother Nature [especially for] young people today. They don’t have an opportunity to hear the sound of a cricket. They don’t have an opportunity to hear the birds singing, because we’ve become so much in technology that we’re getting away from the greatest [thing] of all – Mother Nature.

iRJ: What do you think your legacy will be?

RW: I would hope my legacy would be that I promoted the truth and the beauty of African people and how much our ancestors contributed to the world.

Words By Jarrett Shedd