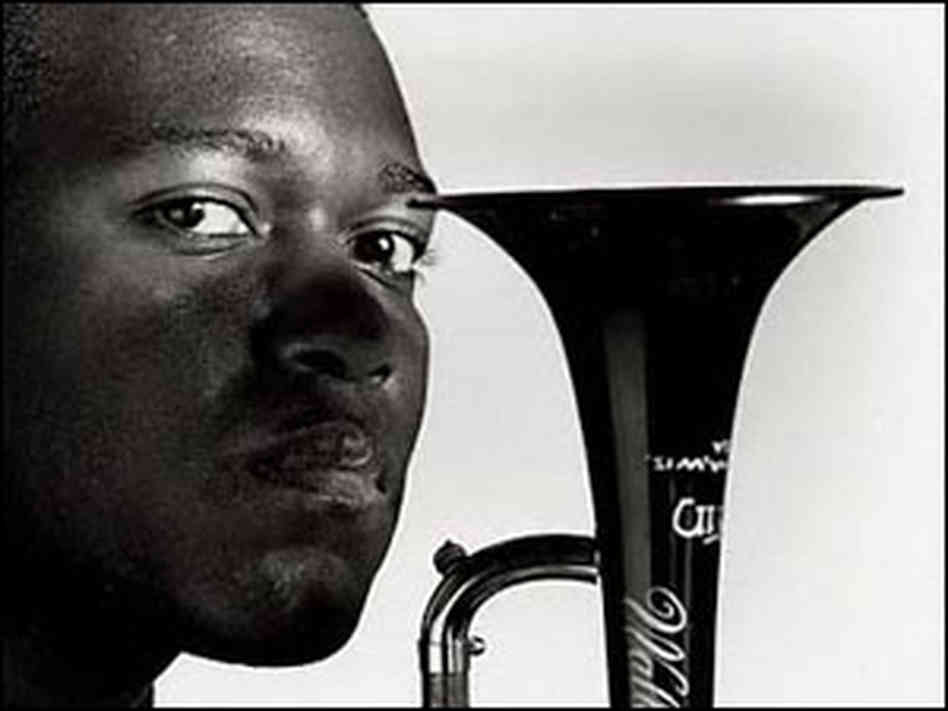

Wallace Roney is a Philadelphia born trumpeter who is an in demand player who has had lots of ups and downs in his career. Although showing promise early on, his professional career didn’t really take off until he was almost 30-years old. Miles Davis has always been Wallace Roney’s most important musical influence, and this has caused some critics to accuse him of direct imitation. No matter how much he has been influenced by his musical heroes, those who are paying attention when listening to Wallace Roney speak or play his horn will realize that he always has something extra of his own to say.

Wallace Roney is a Philadelphia born trumpeter who is an in demand player who has had lots of ups and downs in his career. Although showing promise early on, his professional career didn’t really take off until he was almost 30-years old. Miles Davis has always been Wallace Roney’s most important musical influence, and this has caused some critics to accuse him of direct imitation. No matter how much he has been influenced by his musical heroes, those who are paying attention when listening to Wallace Roney speak or play his horn will realize that he always has something extra of his own to say.

Recently an iRockJazz interviewer was able to talk to Wallace Roney about the important influential musicians in his past.

iRJ: When did you first learn how to play the trumpet, and why did you choose the trumpet over any other instrument?

WR: I started playing the trumpet when I was 5- or 6-years-old. I grew up in a household that loved music. My father was a boxer, my mother was a dancer, and my father loved jazz. They would come over to people’s houses and bring the latest jazz records and sit around and have parties every weekend listening to what was going on [in jazz]. I heard those records at a very young age and I loved them, and I loved the sound of the trumpet. My father had a trumpet that he was trying to take lessons with as well. So when he would go to work I would take his trumpet out and practice it to [see if I could] get a sound out of it.

iRJ: Who was your first instructor, was it Sigmund Hering?

WR: Yep, that was my first teacher. I had taken some lessons at an elementary school called Elvison Elementary. The band teacher was actually technically the first one, but Sigmund Hering was the first concentrated project teacher I had, yes.

iRJ: When did you meet and start working with Clark Terry?

WR: I met Clark Terry when I was 13 [-years-old] and I met Dizzy Gillespie at 12 [-years-old]. My father was in Washington, D.C. and I went up to see my father and he let me go to a club called blues alley. Clark Terry was there and he was playing. He was touring with his group and he let this young boy, this young white trumpet player, sit in with him on his set. This trumpet player, at the time I didn’t think he could play. In all fairness, for a 13-year-old kid he was okay, but I wasn’t thinking like that. I was thinking that he couldn’t play. So after the set was over I went to Clark and I asked him ‘could I sit-in?’ and Clark got mad at me. This is the first time I’ve ever really told this story, but this is true. Clark got mad at me, and I guess he thought that because I saw a young guy up there, he said ‘Sit down and listen. You just seen him up there playing you think you can get up there and play, it doesn’t work like that. Do you have a horn?’ And I didn’t bring my horn with me, that was the first time [that] I didn’t bring my horn. He said ‘Oh you’re not serious, just go back and sit and listen.’ And I was hurt, and I listened to him the rest of the set and I was mad but I still love Clark. Then I went to see Clark again at the Smithsonian Institute not too long after that with his big band. Clark saw me there in the audience, and I guess he felt bad about how he treated me a couple months earlier to that so he was going to take some time and give me a little time. So he asked me to come to the back dressing room, and he said ‘Look, I’m going to give you a lesson.’ He was telling me about doodle tonguing, and he said ‘Now I want to hear you play something, just play anything.’ I had just learned Lee Morgan’s solo with Art Blakey. Clark was shocked, he said ‘Oh, you can play!’ After that me and Clark were best friends for the rest of up to this moment.

iRJ: How did you come to meet Dizzy Gillespie?

iRJ: How did you come to meet Dizzy Gillespie?

WR: Almost the same thing. When I first saw Dizzy Gillespie was in Philadelphia at a place called Spectrum. It was a big concert with Miles [Davis], I went to see Miles and I went to see Dizzy. I was, just like now, in love with Miles’ artistry. So it was Miles’ band and Weather Report with Eric Gravatt and Miroslav Vitous, George Benson, and George Benson’s drummer didn’t show up [so] Philly Joe Jones played, and then The Giants of Jazz with Art Blakey,Dizzy, Sonny Stitt, Curtis Fuller, Al McKibbon and Thelonious Monk. Miles was amazing, but I think Dizzy wanted to let the world know that he could outplay Miles. So as great as Miles was, Dizzy was blowing the house down. The Giants of Jazz stole the show that night. I mean, Miles was still amazing, but Art Blakey took a drum solo on A Night in Tunisia and played so much, the last band was supposed to be Maynard Ferguson and he never got a chance to play. The next time that I saw Dizzy was a year later. Dizzy was playing with his real band, a quartet. Dizzy saw my brother and I in the audience, these two little kids. He stopped in the middle of his show and said ‘What are you two little kids doing here?’ He made us stand up so the audience could see us, and that’s how I met Dizzy. Then he asked me to come in the back, and I guess that I looked like a puppy to Dizzy. Dizzy was nice to me from the very beginning. Dizzy was just telling me about mouthpieces and valve oil and everything about the trumpet. Dizzy has just always been in my life. It became Dizzy and Clark Terry who really taught me a lot about the trumpet during that time, more than the classical trumpeters.

Words by Jarrett Shedd