When truly considering the task of the artist, it is then that we realize that they are the closest we will ever get to meeting gods on Earth. Out of nothing they create that which leaves us speechless. And yet, here we are, once again, attempting to articulate their conception of all things immaculate.

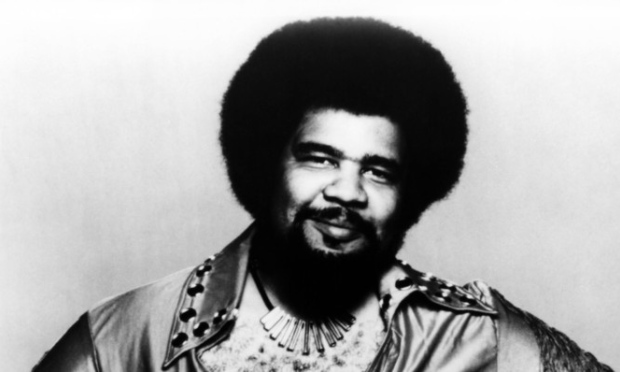

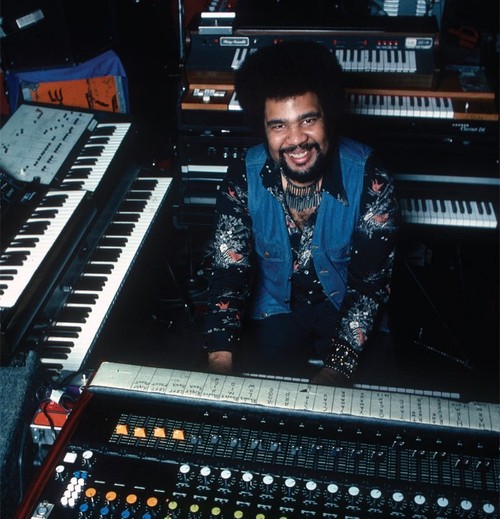

George Duke is one such artist. With a gentle touch, Duke crafted myriad portraits of sound. Eclectic doesn’t even begin to describe the versatility of his palette. Few can lay claim to having had the opportunity to play with Frank Zappa. This claim is equally true when said of Cannonball Adderley. But both? The idea nears the absurd, but not because of the improbable talent it would require, but because of the divergent spaces occupied by the two. It simply doesn’t make sense. Of course, neither did George Duke.

So, how do you capture the entirety of a man as complex as this? How do you properly articulate a career that has defied both tradition and logic?

You can’t. And that is why we turn to his words.

On July 11, 2013, George Duke gave iRock Jazz one of his last interviews before going on tour to promote his latest album, DreamWeaver. Speaking with iRock Jazz, Duke waxed poetically on his music, career, and how the two spoke to his greater perspective on life.

This is George Duke…

iRJ: As prominent artist, people want to hear your signature songs. Is it difficult to deal with fans asking for the classics, when you want to play something new or less recognized?

iRJ: As prominent artist, people want to hear your signature songs. Is it difficult to deal with fans asking for the classics, when you want to play something new or less recognized?

GD: You’re kind of handicapped to a degree. I feel a necessity to play the things that people want to hear, for sure. But at the same time, I feel like it’s a necessity on me to play things that they may have never experienced or something that they don’t hear on the radio all the time. So I feel that pull is definitely there and I try to do both. I have for the last year and a half thrown a Miles Davis tune in the middle of the set. I don’t care if it’s, “Dukey Treats” or “Reach For It,” they’re going to hear some Miles Davis before it… and play it like Miles would play it, so they really experience that style of music because it’s something that they’re not going to hear on the radio every day. So, I look at it this way, it’s pressure, but at the same time it’s what I do. It’s what I have to do.

iRJ: Recently, we’ve seen promoters questioning whether you or other older artists can still connect with audiences, resulting in the addition of younger musicians to a bill, disregarding any potential disconnect in sound or approach. How do you deal with that?

GD: First of all, I think there needs to be that connection between us and them. There’s not enough connection between us as artists that have been around awhile and the young artists that are out there now trying to take the music in another direction. I think there needs to be more of that as opposed to less. I think we actually need to work together. I mean, it’s not just appearing on the same stage, but I mean we need to be in the same band. There needs to be something put together where we can actually experience playing with each other one-on-one, so our notes intersect. That’s the way you learn. And so I think that is highly important. I got no problem at all. If they want me to open for Robert Glasper, I ain’t got no ego. And music shouldn’t have that kind of ego. It’s got nothing to do with that, at least from me. But I understand what you’re saying. That’s the politics of it. I try as much as possible to stay away from the politics of music.

iRJ: What do you think are the circumstances under which an artist like yourself can get the same sort of mainstream recognition that was had in the past?

iRJ: What do you think are the circumstances under which an artist like yourself can get the same sort of mainstream recognition that was had in the past?

GD: Back in the day college radio was very important to us. There used to be college tours. That doesn’t exist too much at all anymore. College radio is still important, but at the same time I also think alternative radio is important. Whatever you can get in terms of that. Obviously, there are a lot of forces that have gotten together on the internet, which kind of helps out a lot, but if we could get a little bit of even the quiet storm-type format back because that really put us on the map. It gave us some place to live, in terms of people would come into a town and say ‘Hey, we’d like to hear some George Duke or some David Sanborn…’, they knew that they could turn to this station and hear it. Well you can’t do that anymore because the way it changed when it went to a smooth jazz thing kind of kicked us out of it.

iRJ: Your contemporaries are all significant in their own right. Naturally, you receive a push to join them on stage. Do you enjoy playing in that sort of “all-star” ensemble setting? Or do you prefer playing with your own personal band?

GD: I do a combination of the two. The majority of the touring for this new album will be with my band. I can’t use an all-star band to do that. It’s just impossible. I personally don’t care to go out and do too much of that all-star kind of stuff. Of course, I do a bit with Stanley Clarke and with Al Jarreau, but there’s a different connection there. And I also do the same thing with Marcus Miller and David Sanborn, but that was a whole different situation than going out with like three sax players. That I don’t really care to do. Because that way I’m just playing, “Reach For It,” “Dukey Sticks,” “No Rhyme, No Reason” and going home. That’s not near interesting to me. See, the reason I got into the business was not to play hit records. That’s not satisfying musically to me. I’d rather stay home and play by myself. Now I don’t want to give anybody the wrong impression that I don’t love playing, “No Rhyme, No Reason, “Dukey Sticks,” because I love them, absolutely. And they bought me a house and gave me some money, kids all of that [laughs]. And that’s all cool, but that’s not enough, man. Love extends way beyond that. So I gotta be able to play some other music that’s freer, some other music that allows the band to express itself so it’s not just a carbon copy every night with everybody playing the same notes. That would just be awful. I might as well play in Vegas! So I choose not to do that. And I’m offered that all the time, believe me. And I basically say no. I’ll do something that’s interesting like when David Sanborn and Marcus Miller call and say, ‘Are you interested in this thing’? That’s a different thing. DMS. We can become a band as opposed to just a bunch of guys playing their hits. And we did.

GD: I do a combination of the two. The majority of the touring for this new album will be with my band. I can’t use an all-star band to do that. It’s just impossible. I personally don’t care to go out and do too much of that all-star kind of stuff. Of course, I do a bit with Stanley Clarke and with Al Jarreau, but there’s a different connection there. And I also do the same thing with Marcus Miller and David Sanborn, but that was a whole different situation than going out with like three sax players. That I don’t really care to do. Because that way I’m just playing, “Reach For It,” “Dukey Sticks,” “No Rhyme, No Reason” and going home. That’s not near interesting to me. See, the reason I got into the business was not to play hit records. That’s not satisfying musically to me. I’d rather stay home and play by myself. Now I don’t want to give anybody the wrong impression that I don’t love playing, “No Rhyme, No Reason, “Dukey Sticks,” because I love them, absolutely. And they bought me a house and gave me some money, kids all of that [laughs]. And that’s all cool, but that’s not enough, man. Love extends way beyond that. So I gotta be able to play some other music that’s freer, some other music that allows the band to express itself so it’s not just a carbon copy every night with everybody playing the same notes. That would just be awful. I might as well play in Vegas! So I choose not to do that. And I’m offered that all the time, believe me. And I basically say no. I’ll do something that’s interesting like when David Sanborn and Marcus Miller call and say, ‘Are you interested in this thing’? That’s a different thing. DMS. We can become a band as opposed to just a bunch of guys playing their hits. And we did.

iRJ: When you think of DreamWeaver, considering the sentiment behind it, is it bittersweet?

GD: Yes. Especially the songs that were specifically written for the record, the ones that were written on the boat when I first came up with the ideas for the songs, “Missing You,” “You Never Know”, “Round The Way Girl”, and even “Happy Trails”, which I had an idea for on the way back home. And so those are bittersweet. Some of those that came later are not as bittersweet, no. Tunes like “Trippin”, where I talk about how I was raised on music from a brothel next door, so to speak, that’s not true [laughs]. It was just a guy’s room. Those all came out of this audio soup. But some of the other tunes, no, they’re different. And I don’t want people to get an idea that this is a morbid record, because it definitely isn’t. “Change The World,” “Jazzamatazz,” some of the long jam sessions, those are great tunes, which are hopefully uplifting.

iRJ: At the end of the day, what do you want people to take away from this album?

GD: I think life experience. You never know what life will bring. Even though you know that winter will turn to spring, something’s going to come in your life that’s going to wring your neck. And you never know what it’s going to be and that’s what I started thinking about on the boat. And it just came out. Lyrics just came out. Because you never know and you gotta be prepared to deal with it, but you never are. Look, man, I’m still weeping from it now a year or so later. And probably will go on. If I get through this first year, if I live through this first year, I’ll probably be doing great. I understand why so many spouses die within a year after their spouse dies. It’s physical; it’s spiritual; it’s a very strange thing. This stuff is connected, but I’m determined to get through it. Believe me.

iRJ: What is the biggest lesson that you’ve learned from all of this – about yourself, about your life or about the meaning of your music?

iRJ: What is the biggest lesson that you’ve learned from all of this – about yourself, about your life or about the meaning of your music?

GD: I guess, the old Magic Johnson thing, “Life goes on”. I hate to minimalize myself, but we’re all small. It’s like the lyrics to, “You Never Know”, ‘We’re all small in the midst of it all and you can’t s escape when your number’s called…’ It doesn’t matter. We’re little folks in this hodgepodge of whatever this is and blessed that God has given us a chance to be a little creative, a little wee – wee bit godlike by putting our little finger in that audio soup and creating something that can make something more positive for the world. And I think that’s what’s very important and what I’d like to be remembered for – is bringing some positivity instead of some negativity into this world.

In moments such as this, we often use the cliché that one lives on through their art. In the case of George Duke, I wouldn’t call it hyperbole. His work was etched in his joy, in his pain, in everything that made him beautifully human. In spilling his heart, he made the most authentic music possible. When you hear his music, you, too, hear the pieces of a man. George Duke will forever live on and for that we are more than thankful. We are blessed.

By Paul Pennington