It’s often said that sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good. This ideal is mostly applied to the sporting world, but when it comes to Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Larry Graham, his greatness derives from a series of unexpected events. You’d be hard pressed to find anyone more synonymous with Bay Area Soul music. His revolutionary thumping and plucking style on bass with Sly and the Family Stone and Graham Central Station is arguably the most influential innovation of the instrument outside of the improvisational mastery of James Jamerson. But believe it or not, Graham was never supposed to be a bass player:

“I started playing bass when I was working with my mother, who was a pianist and vocalist. We worked together as the Jill Graham Trio – her on piano and me on guitar, and a drummer. In this one club that we worked in, they had an organ with bass pedals. I just played the bass pedals with my foot and at the same time as playing the guitar, so we sounded full. We got used to that, but then the organ broken down. So, I went down and rented a St. George bass from Music Unlimited – the reason I rented was so I could take it back once the organ was repaired. As it turned out, it couldn’t be repaired, so I got stuck on the bass. Then, my momma decided that there would be no drums; just piano and bass. Then I started thumping the strings to make up for not having that backbeat. It’s kind of like playing the drums on the bass. I wasn’t trying to come up with something new, I just do what was needed. That’s how I developed that style.”

After joining Sly and the Family Stone in 1967, bass players all over the country were perplexed by the sounds they were hearing on hits “Dance to the Music”, “Thank You (Falettine Me Be Mice Elf Agin)” and “M’Lady.” In fact, it was on the latter that Graham’s addition of fuzz to his bass that involuntarily ushered in a level of technological sophistication that was, at the time, only reserved for electric guitars:

“Actually it came from using a distortion pedal, some folks call it a fuzz tone. Because I played guitar first and I was into guitars players, I wanted to know what the bass would sound like with the same pedals the guitar players were using, and that’s how I really came up with the concept of plugging my bass into distortion. That’s that sound you hear on “M’Lady”, “Dance to the Music” and some other songs. Now, they make design [distortion pedals] for bass, too – wah-wah, distortion – but back then, it was all for guitars.”

After six groundbreaking years with Sly Stone, Graham went on to set his own mark in music, founding and fronting Graham Central Station. Believe it or not, this ultra-funky extension of the Family Stone almost didn’t happen:

“There wasn’t an intention to start another band – stuff like that just happens in my life, huh? My intention was to build this band around “Chocolate” Patrice Banks and I would be the writer and producer of the band Hot Chocolate; I wasn’t going to be in the band at all. What happened was they were playing a gig at this club in San Francisco. The place was packed out, lot of excitement in the air. When it got to the end, the urging of the crowd caused me to go with the band on the last song, and there was an instant click. It just went into another gear. Everybody pretty knew that something had just happened (chuckles) that’s very special, and I realized it too. So, I ended up changing the name of the band from Hot Chocolate to Graham Central Station, replaced the bass player with myself, used the songs we already recorded and added new songs to it, and we came up with the first Graham Central Station album.”

With a catalog full of concrete-busting funk, such as “I Want to Take You Higher” “Release Yourself” and “The Jam”, Graham is best known for his tender torch ballad, “One in a Million”. Not only did this classic love profession nearly miss being released, but it was the catalyst for his audience reaching its greatest numbers:

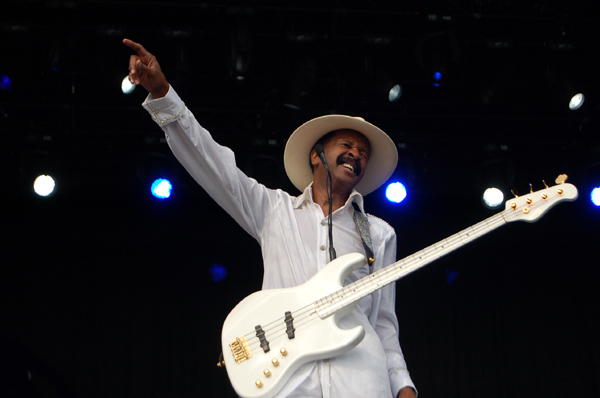

Larry Graham and Graham Central Station

“When I recorded it, it kind of sat there in the studio; it was, like, trying to wait ‘til you can hear the mix, ‘cause that’s so important. You can have the song recorded and everything, but the mixing – it’s like if you have all the ingredients to a great meal, but you don’t cook it right, it’s not going to taste so good. So, we’re coming home from the Kingdom Hall one day, my wife and I, and all of a sudden I could hear in my head exactly how the record should sound. It was on a Sunday and the engineer wasn’t available. I didn’t want to lose it, so my wife and I went into the studio I built in the guest house where we used to live in L.A. I said, OK, you take the right hand side of the [mixing] board and show you the moves, and I’ll take the left hand side, and we mixed it ourselves. What you hear on the record is what we did. I was really happy with it, but when the record company heard the album, they weren’t for me putting out that ballad. They wanted to go with something more up-tempo, featuring the bass. But, it just so happens that my lawyer had in the contract the right to choose singles for my album. So, even though they didn’t like the song, I exercised my right and put it out anyway. When it became a hit, then they jumped on the bandwagon and supported it. It became the signature song. What’s interesting is we started doing a tour and a lot of people coming to the shows did not make the connection between Larry Graham, the bass player and Larry Graham the vocalist. So, a lot of people came thinking they were going to hear a whole concert of “One in a Million” type songs from this artist; they’d come in their suits and ties, looking like they’d just come from dinner. Then you had my fans who’d come to hear the funk, coming in with their regular street clothes. So, you have this mix in the audience, looking at each other surprised that they’re there to see the same artist.”

Unintentional or not, accidental or premeditated, Larry Graham’s career is responsible for the existence of some of music’s greatest talents, from Louis “Thunder Thumbs” Johnson and Marcus Miller to Victor Wooten and Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers – generations of timeless music, all thanks to the lucky roll of the dice that’s been Larry Graham’s fate.

By Matthew Allen