Betty Davis

With a new task ahead, Betty Davis embarked on recording her first solo album. She had plenty of songs to choose from, including compositions meant for the Commodores, like “Game is My Middle Name”. As a writer, she would’ve entrusted Just Sunshine to distribute her songs to artists they saw fit, but since she’d be the one recording them, the potential of the songs could be fully realized. To fulfill that potential, she needed the right producer.

Luckily, one of her heroes was available. “I told Michael Carabella, who was in Santana at the time, that I was going to record an album and that I was looking for musicians. So, Michael introduced me to Greg [Errico].” Errico, the propulsive drummer of Sly and the Family Stone, assembled a cast of musicians that would be perfect compliments to the funk-driven songs Davis had created; his Sly Stone band mate Larry Graham on bass, Santana members Neal Schon on guitarist (later of Journey) and Victor Pantoja on congas, and background vocals from the Pointer Sisters and future disco-king/queen Sylvester.

“I was very impressed,” Davis recalls about the sessions. “I recorded all the time in the day time. I would do my arrangements for the music and I would take them to the musicians who were going to be carrying the songs, then we would record. I would do my vocals at night and that was basically about it. It was very simple and very easy going.”

In addition to Errico’s production, Davis also assisted in the direction of the band, pointing them in the right direction, yet letting their form shine. “She knew where she wanted us to go, but she allowed us to be ourselves,” says Larry Graham. “It was a remarkable atmosphere of freedom.” Perhaps the freedom of her music was a combination of her liberated ideals and Miles’ musical influence. “My music is basically very free form,” she says. “It’s really like – I hate to use that word ‘Jazz’. It really cubbyholes them into something from a different era – but it’s very progressive.”

Progressive is an understatement. Musically, 1973’s Betty Davis expounded on Sly Stone’s integrated Funk and Pop with the aggressive natural of Rock & Roll. Bringing all together was Betty’s voice – a gruff, dense release of unbridled passion. As if the music was not revolutionary enough, the way she presented it was also a radical cultural shake-up. Further driving home her liberating musical statements like “Steppin’ in Her I. Miller Shoes”, and “Anti-Love Song”, was her innovative sense and attention to style.

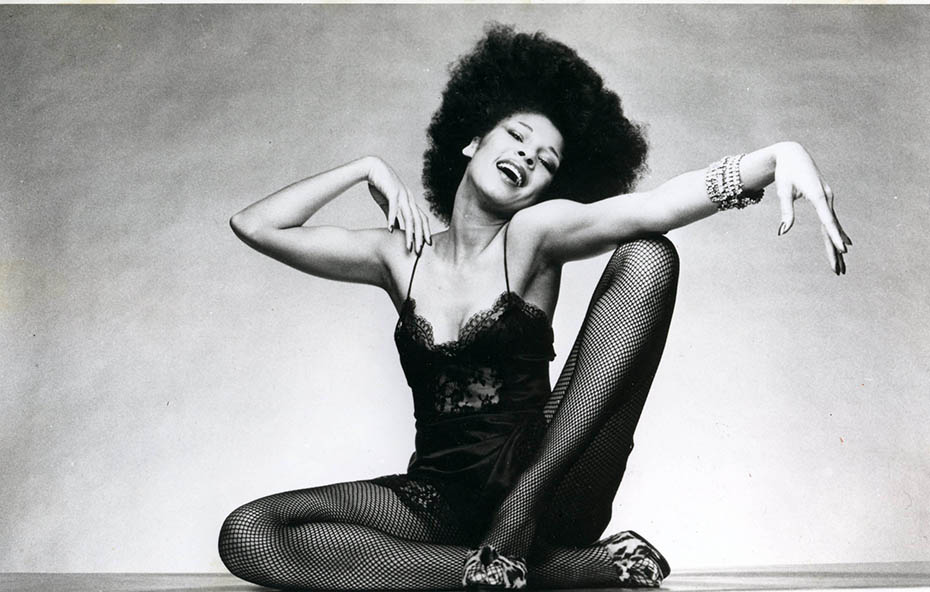

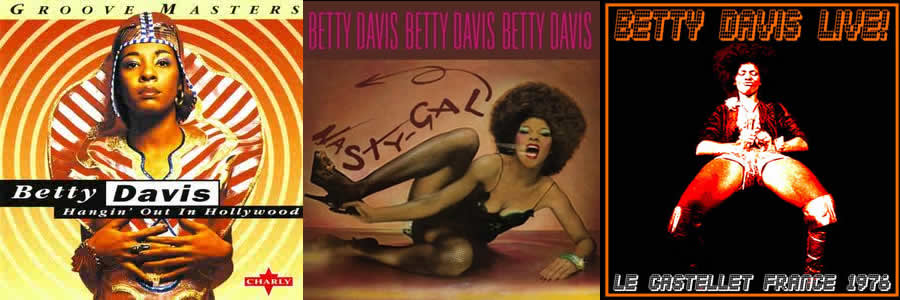

Her album cover for Betty Davis featured her in her denim short shorts, a turquoise blouse and thigh-high silver boots, a suggestion from Eric Clapton, whom she was dating at the time. “He told me I’d look great in silver boots,” she recalled with a chuckle. That sense of fashion extended to the stage as well. She’d often adorned sexy camisoles, fancy jackets and hulking platform shoes, a visual proponent to her material. Davis’ sexual imagery on her 1970s album covers coincided with the kinky and adventurous album covers practiced by fellow progressive black music forces like George Clinton’s Parliament/Funkadelic camp (Standing On the Verge of Getting’ It On and Free You Mind…and Your Ass Will Follow) and the Ohio Players ( Pain and Skin Tight).

Betty Davis Album Covers

Enlisting designers like Todrick Wong (Pablo Picasso) and Larry LeGaspi (LaBelle), Davis was ahead of the curve when using her body as a canvas. This intuitive fashion IQ came from her time studying at New York’s Fashion Institute and her modeling career during the 1960s. Through the Park Avenue agency Wilhelmina, she landed gigs with Ebony, Seventeen and was one of the first black models to be on the cover of Glamour magazine.

Through the remainder of the 1970s, Betty Davis continued her envelope shoving career with three albums, two on Just Sunshine and one on Island Records. She took a historical leap for her sophomore effort, 1974’s They Say I’m Different, by deciding to produce the LP herself. “I just wanted to do it, that’s all,” Davis spoke of stepping into the producer role. “Greg had done the first album and I felt I could do the second album. It’s wasn’t that I disapproved of Greg or anything like that. It was just I wanted to do it on my own.” While admitting it was harder to wear four hats of producer, writer, arranger and artist, she says the process didn’t add any pressure on her.

Davis recruited a new lineup of musicians, including famed percussionist Pete Escovedo and bassist Louis Johnson (her cousin). This was quite an understated milestone in music history. In succeeding decades, the list of prominent female producers is short: Angela Winbush, Lauryn Hill and Missy “Misdemeanor” Elliott are some of the few that have broken the chain. Davis wasn’t aware that she was trailblazing, but understands the barriers women face when it comes controlling their own music. “I think it depends on what you what you want to do as an artist; that’s what it boils down to,” Davis informed. “If you take a road where you’re a woman and you wanna be a producer, well you’re going to encounter some feedback for that. It depends on what you want to do as an artist and that’s the road that you take, regardless of the lumps, the bumps or the thumps.”

On They Say I’m Different, and later albums Nasty Gal (1975) and Crashin’ from Passion (1976), Davis continued to create anthems of rebellion and sexual sovereignty. Lyrically, she left no room for ambiguity, but the character of the music and words offered a more abstract and meaningful allegory. She wasn’t just singing about great sex and expensive clothes, but about being fearless, being committed to your art and making no apologies. It was that attitude that may have contributed to the rationale behind why she never broke through on a commercial level. She received scathing reviews from both the press and organizations like the NAACP for her riotous music and on-stage behavior.

The truth of the matter was she was living two lives, one as the dynamic songstress and the other as a quiet songwriter. “My lifestyle and my music were entirely different; they were separate,” Davis confesses. “I lived a much more quiet life than the records would suggest.” She concedes that her lyrics were born out of her unconscious observation of her musician friends and the nameless practitioners of New York night life. “I was always inspired by our environment and by the people. I would go to a club and I’d observe certain things. It was things like that that would happen.” To this day, despite alleged counter punches to her critics, such as “Nasty Gal” and “Dedicated to the Press,” she holds no ill will or judgment to the media. “The press, they have to make a living, and they make a living by doing what they think is best. They have families to support, whether they do it in a good way or they do it in a bad way, you know what I mean?”

In black music culture, we are impressed by those who achieve massive crossover success, and although we also find ways to embrace those lesser known, they’re not given the fiscal stability that others might enjoy. Today, artists are divided into two basic categories: superstars and unsungs. The latter outnumbers the former by an overwhelming ratio. For every Michael Jackson, there are 10 Alexander O’Neal’s. For every Aretha Franklin, there are 10 Vesta Williams’. While only a selected few get to taste the sweet nectar of crossover success and wealth, many of the rest live, at best, a modest existence while floundering in obscurity.

The music business in the 1970s was not so different than it is now, heavily concerned with the marketability of an artist above the equal exposure of the product. “I think it’s about being commercial and making money,” Davis explains. “Being commercial and being creative are two different things; they don’t go hand-in-hand. If you can make them go hand-in-hand, you’re a very good business person and very few people can do that.” Indeed, Davis suffered for her labels’ lack of ingenuity, and since her retirement in 1980, she’s lived a quiet life and hasn’t been able to reap the rewards of her innovative work. “I think that if I would’ve been packaged differently, my career would’ve been different. That’s what I feel. I would’ve sold more records; I would’ve been more financially secure.”

The music business in the 1970s was not so different than it is now, heavily concerned with the marketability of an artist above the equal exposure of the product. “I think it’s about being commercial and making money,” Davis explains. “Being commercial and being creative are two different things; they don’t go hand-in-hand. If you can make them go hand-in-hand, you’re a very good business person and very few people can do that.” Indeed, Davis suffered for her labels’ lack of ingenuity, and since her retirement in 1980, she’s lived a quiet life and hasn’t been able to reap the rewards of her innovative work. “I think that if I would’ve been packaged differently, my career would’ve been different. That’s what I feel. I would’ve sold more records; I would’ve been more financially secure.”

The 21st century is riddled with the musical offspring of Betty Davis. From Madonna to Lady Gaga, today’s chart toppers owe a debt to Davis, in particularly black female provocateurs. The fact that women of color can succeed in the music business by celebrating the sensual side is nearly solely attributed to artists like Davis who took the brunt of the bullets of the firing squad. Although many have achieved more substantial notoriety and fortune, not one has been able to masterfully balance every aspect of what gets them their respective attention.

Starting with the age of the music video and in our 24 news cycle, the time tested sex sells ideal hits home with viewers, for better or worse, more so than the music every could. Betty Davis was not only ahead of her time when it came to music, she was able to do something that perhaps no female artist has been able to accomplish since; finding a perfect balance between singing, songwriting, producing, performing and controlling her own image without allowing the image to overshadow the music. “The whole thing just, sort of, came together. I can’t really explain it. It’s like a total creative thing that happened. I mean, my music, my visuals, everything was one. I think when you’re a true artist, that’s how you have to be.”

Betty Davis was the total package, which has led to her iconic stature to all those informed with her legacy. The difference between Betty Davis and those who unwittingly walk in her footsteps today is simple: Hit records and classic records. Those who want to make hit records make timely music, and those who want to make classic make timeless music.

Betty Davis is timeless.

Words by Matthew Allen