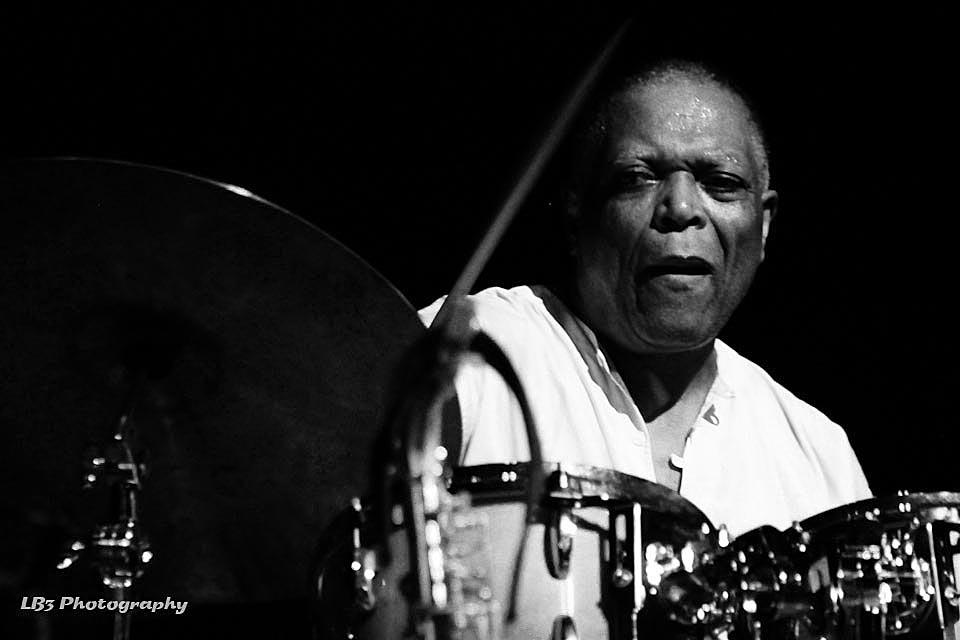

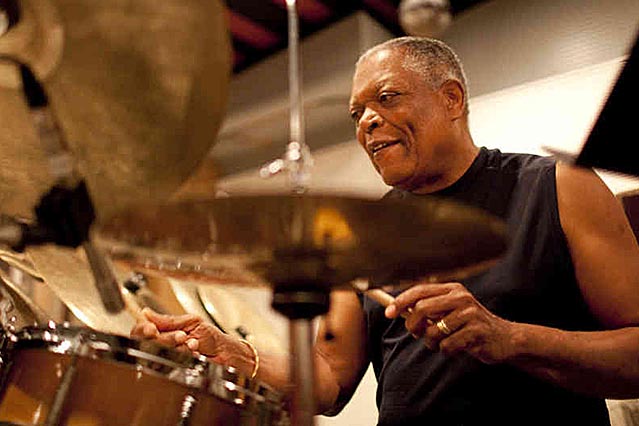

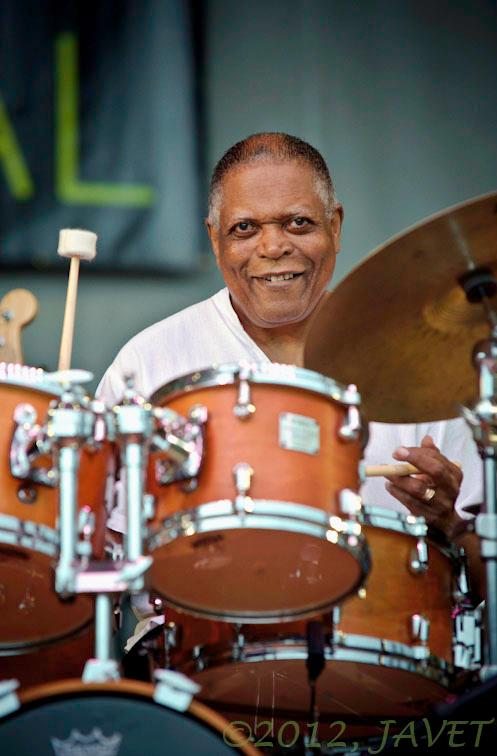

Billy Hart, photo by Louis Byrd III

Billy Hart, photo by Louis Byrd III

Billy Hart is one of the wise elders of Jazz, or Modern American Classical music, as is his preferred title. He has not only performed and recorded with some of the great figures of the music, such as Herbie Hancock and Miles Davis. He also has led his own bands, involving many artists who later rose to fame, such as: Steve Coleman, Branford Marsalis, Kevin Eubanks and Bill Frisell.

Still an active performer, and educator, Billy Hart also teaches music courses at numerous top universities in America. And he leads a critically-acclaimed quartet, featuring Mark Turner, Ethan Iveson and Ben Street, which is set to put out a new release in the spring. He offers some profound insight into the history of the music, and its place in the changing politics of the time.

iRock Jazz: You are sometimes called by a Swahili name Jabali, how did that come about?

Billy Hart: There was a guy named Ron Corenga who started up a lot of groups, such as CORE and SNCC. CORE stands for Congress of Racial Equality and SNCC stands for Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee. People like these were the ones who started things like Kwanzaa. James Mtume gathered many of us, and we rode around on a truck, and put in the first Afro-American mayor of Newark. As payment; as a reward for [having done] that, I got my name, which is Jabali. I wasn’t the only one; Herbie Hancock got a name, too, Mwandishi, which is also the name of the first record I did in his band. Mwandishi in Swahili means composer.

Around that time, people like McCoy Tyner and John Coltrane, their music had so much energy that the people who didn’t know would assume it was for some kind of Black-power push, when they asked Coltrane, “What are you trying to do with your music?” He said, “I simply want to be a force for good.”

At that time, the tendency was to think of those people “making waves” as being terrorists instead of making things better for everybody, not just for the Afro-American situation. That way of thinking, that clearer and more fair way, it lessens the Karma (if you want to consider them) of the oppressor. There was a lot of Afro-American philosophical thought which came along with us combating the racism of the time.

iRJ: What do you think of the new generation of jazz musicians?

BH: Every generation transforms art into its own image. It’s not the art that changes; it’s the image. In other words, Robert Glasper isn’t hitting the music any harder than Louis Armstrong did it…I don’t care how popular it seems. It’s not any more popular than Louis Armstrong was in his day. The style might be a little different, but the human feeling that it produces is the same. It’s a cultural kind of thing, depending on who else relates to it. It could be a little more or less exotic; depending on whether you are hearing the music for the first time in China, or hearing it at some university in America.

iRJ: How can Jazz regain popularity?

BH: First of all, this is what I do for a living this is how I put my kids through school; and this is how I bought my house. Gary Bartz owns his own home; I own my own home. As bad as you want to say that it is, we are still living a relatively middle-class life. I am still looking at it as something that was predominantly influenced by the Afro-American. I am not like one of these guys, like Nicholas Payton, who says this is Black music. It’s American as far as I’m concerned. it’s just that a huge influence of it is African.

And, I guess, there was such a condescending attitude (or belief) coming from the European community in the early days that it was such a shock for them to experience the genius of these musicians, who were considered, in their opinion, not to even have a brain. They were totally shocked that these people could play music on this level. They didn’t even let Jackie Robinson into baseball until 1947. They didn’t let brothers into the Army for a long time; they didn’t think they had courage. It’s odd to think about what people perceived the Afro-American to be.

The influence of the Afro-American on this music…it’s not this separate marketing thing. Aretha Franklin is jazz; Ray Charles is jazz; James Brown is jazz. Not only do I like improvised Afro-American music, I like the extreme part. I like Cecil Taylor; I like the last decade of Coltrane’s music. The music I like is really hard to listen to. But, the reality, to me, is that Otis Redding is still a big part of what I do; Jay-Z is still a big part of what I do.

So, as far as jazz coming back [is concerned], it just has to be accepted. Just like the European community has theirs; it [Jazz] has to be recognized as American Classical music. The higher mindedness of having a multi-cultural country, for the first time in America, and the progress from the industrial revolution to the technological revolution has advanced humanity so fast it’s hard to tell where the folk music (or the dance music) leaves off, and the classical music takes on. What took Europe 500 to700 hundred years to develop, where they can tell the difference between their folk music, and their classical music, we have had barely 100 years to put that [distinction] together. In every culture on the planet, the way I see it, the music develops into a sophisticated thing that we call classical music, which perpetuates. While many styles of music, which are basically the same, are being marketed with new titles, like rock, and then heavy metal; the rap; then hip-hop.

iRJ: As an educator, what are you finding in the classrooms today?

iRJ: As an educator, what are you finding in the classrooms today?

BH: The sociopolitical danger of capitalism; of being part of this country, is that the history is lost. They say if you don’t know your history, you are doomed to repeat it. If you want to have paranoia and say there is a conspiracy between the higher and lower classes, then the higher classes seem to try to keep the lower classes from being educated. You need to have a system, so you can know a lot more [information] about your history; fore [knowing] that would solve a lot of the problems.

I am part of the education system. For me, it is really important that my students learn the history. No matter how much they “feel they are into”[listening to] Steve Coleman, Nicholas Payton, Wynton Marsalis, whomever it is today; whoever is the current “whatever it is.” You better know something about Jelly Roll Morton; you gotta know who you are. How did it get to where it is now? How are you going to make anything better if you don’t know from where it came? If anything, you might be messing around, and making it worse.

iRJ: Do you have any new projects coming out?

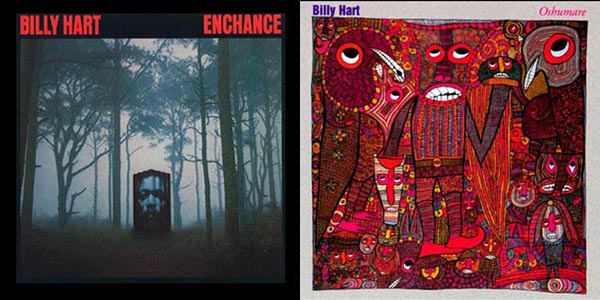

BH: What! Have you heard any of my early records? My first record was called Enchance, with Don Pullen on piano, and two bass players; Dave Holland and Buster Williams; and two saxophones, Oliver Lake and Dewey Redman; two trumpets, Eddie Henderson and Marvin Peterson, who they call Hannibal — who frequently guests with Symphony Orchestra around the world.

A record I did with Steve Coleman, and Branford Marsalis, was called Oshumare, which is a Nigerian term, meaning “goddess of the rainbow.” The next record was called Ra; with Kevin Eubanks, and Bill Frisell on guitar.

If any of those other guys had had their name on that record, the record would have been more famous or more noticeable. There is something about this country that if you are a drummer, the record can go unnoticed. But, just recently, my last couple of records has gotten me a lot of attention. The current band I have; with Ethan Iveson, Ben Street and Mark Turner, made one album for “HighNote” [label]; called Quartet. And [another album called] All Our Reasons, for ECM, earned me “drummer of the year” from jazz journalists.

Speaking with Billy Hart has been an honor for iRock Jazz. He has a new album; set for release in the Spring, featuring his steady, working quartet of Iveson, Street and Turner. The next highly anticipated chapter of a group; with near-psychic, improvisational interaction; honed from their many years working together, is sure to be another exciting example of the creative outcome, which has been made possible with an artistically potent figure, Mr. Billy Hart spearheading at the helm.

Words by Willow Neilson