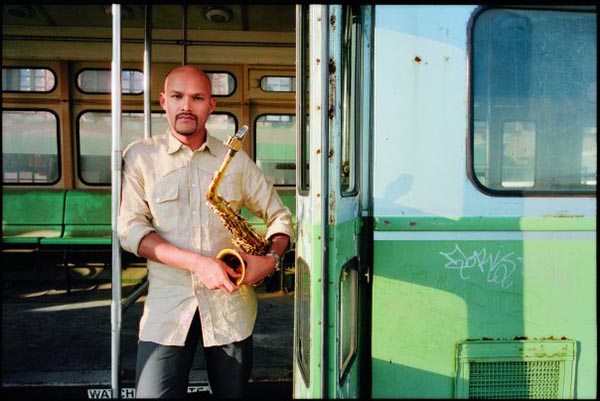

Multiple Grammy-Award nominee and Guggenheim and MacArthur Fellow Miguel Zenón represents a select group of musicians who have masterfully balanced and blended the often-contradictory poles of innovation and tradition. Widely considered as one of the most groundbreaking and influential saxophonists of his generation, he has also developed a unique voice as a composer and as a conceptualist, concentrating his efforts on perfecting a fine mix between Latin American Folkloric Music and Jazz.

Born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Zenón studied classical saxophone at the Escuela Libre de Música in Puerto Rico before receiving a bachelor’s degree in Jazz Studies from Berklee College of Music, and a master’s degree in Jazz Performance at Manhattan School of Music. Zenón’s more formal studies, however, are supplemented and enhanced by his vast and diverse experience as a sideman and collaborator. Throughout his career he has divided his time equally between working with older jazz masters and working with the music’s younger innovators – irrespective of styles and genres. The list of musicians Zenón has toured and/or recorded with includes: The SFJAZZ Collective, Charlie Haden, Fred Hersh, Kenny Werner, David Sánchez, The Village Vanguard Orchestra, The Mingus Big Band, Bobby Hutcherson and Steve Coleman.

His latest release, Oye!!! Live in Puerto Rico (Miel Music, 2013) features the debut recording of The Rhythm Collective, an ensemble first put together in 2003 for a month long tour of West Africa. The group includes Aldemar Valentín on electric bass, Tony Escapa on drums and Reinaldo de Jesus on percussion; all native Puerto Ricans and some of the most coveted musicians in their respective fields. Fed by the energy of the full capacity audience in attendance, the group delivers a high intensity performance which includes originals by Zenón and covers of Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va” and Silvio Rodriguez’ “El Necio”.

His latest release, Oye!!! Live in Puerto Rico (Miel Music, 2013) features the debut recording of The Rhythm Collective, an ensemble first put together in 2003 for a month long tour of West Africa. The group includes Aldemar Valentín on electric bass, Tony Escapa on drums and Reinaldo de Jesus on percussion; all native Puerto Ricans and some of the most coveted musicians in their respective fields. Fed by the energy of the full capacity audience in attendance, the group delivers a high intensity performance which includes originals by Zenón and covers of Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va” and Silvio Rodriguez’ “El Necio”.

iRJ: Oye!!! Live in Puerto Rico that was released in May 2013, what is Oye and the meaning behind this record?

MZ: ‘Oye’means listen. It’s like you’re forcefully telling someone to listen. This is a band that came together about ten years ago specifically for a trip that we made to a few different countries in South Africa. This was all part of a program that used to be called the Jazz Ambassadors, which was put together by the Department of State and the Kennedy Center. Because of the regulations on instruments, I thought about doing something with instruments that were easy to carry; electric bass, drums, and then percussion. A lot of the music on this record was written or developed during that tour.

iRJ: Did you work with any of the natives of Africa in the the countries you visited?

MZ: It’s a combination of official performances where you play at an embassy or for the delegates of that specific country. We visited six different countries: Guinea, Cameroon, Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. We interacted with a lot of musicians [while on the trip].

iRJ: With music having its own dialect and being universally understood, how easy is it to communicate with musicians from all over the world?

MZ: Well in this case, when we play with this band, it is coming from a rhythmic standpoint of Caribbean and Puerto Rican music. That in itself created a natural connection with many of the musicians and the audience because they recognized a lot of the stuff we played as having the roots there. Certain folkloric elements that you find in this type of music are very grounded. You will recognize elements that go farther down than just notes and chords.

iRJ: How sophisticated would you say musicians in other countries are compared to the United States?

MZ: I’ve had the chance to visit many (what other people would call) third world countries, like various countries in Africa. I’ve been to Cuba, Brazil, and other places in South America. The main difference in approach has to do with musicians that have musical training and musicians who don’t have “training” as in a school or conservatory. To me, there is very little difference in terms of skill or abilities as musicians but the way they think can be different.

iRJ: With some of these third world countries where they don’t have the same accessibility to instruments and education, are you surprised in their ability to play at the level they can play.

iRJ: With some of these third world countries where they don’t have the same accessibility to instruments and education, are you surprised in their ability to play at the level they can play.

MZ: I wouldn’t say I’m surprised because folkloric music to me is the purest music there can be. That they are able to do what they can without training – kind of proves my point in a way. At the same time, it is still amazing that they are able to interact and adapt in a very natural way with musicians who have that training. Music has that ability to leave the classroom. It becomes what music has always been – it was born out of regular people. It always has had this purpose of being an alternative language. Being able to witness this in many different situations can prove that point.

iRJ: If jazz musicians didn’t have the training and education that the new ones do today, but organically started to make music in the way hip-hop was born, do you think that would better serve jazz today? Do you think that the educated musician becomes a scholar more so than a musician for the people?

MZ: Well, a lot of the people we admire didn’t go to school or read music. Those guys played by ear and thought about it in a totally different way. But I don’t think it would necessarily help to go back to this folkloric way of looking at music. But if jazz hadn’t gone through the process of being so immensely influenced by European classical music and everything that brought with it, from bebop until now, it would be different but I don’t think it would be better. There is nothing wrong with being informed and the fact that you can get that information so easily is a testament to the way the world and technology works. It’s how things move forward. I do think there should be a balance between what’s going on in the mind and what’s going on in the heart. That balance is still there in a lot of the music I like.

iRJ: Are you surprised that there is a new resurgence and interest in Latin American Jazz?

MZ: I wouldn’t call it something new. I think this is something that has been going on for a long time ever since Dizzy Gillespie, Machito, and Chano Pozo started collaborating. Charlie Parker played with the Machito band and all that stuff was happening even before with Jelly Roll Morton. This has all been a part of jazz music for a very long time. It’s creating more of a presence of Latin America in the jazz world now as a reflection of what’s going on in the country. That’s reflected in politics, art, movies, and everything as we have more Latin Americans living here. We could get into the idea of what “Latin Jazz” means and I’m not really a fan of the term, but what I think is interesting is that Latin American music has been incorporated into many different styles of music in a very natural way. Also, jazz music itself has absorbed a lot of ideas from Latin American music, African music, and music from all over the world. It has become a part of the language when I listen to Chick Corea, Pat Methney, or Herbie Hancock, and I could go on. People don’t think about those elements as Latin because the musicians are American. The lines have started to become blurred because of the ever growing presence of Latin American musicians in jazz and the idea that jazz is drawing from this music to grow as a language.

Miguel Zenon and The Rhythm Collective

Miguel Zenon and The Rhythm Collective

iRJ: If you wouldn’t call it Latin Jazz what would you call it?

MZ: We can go back and forth with this and there are some people who don’t want to call “jazz” jazz but I think it all falls under the same umbrella. At the core of it, we’re dealing with a language that comes out of the same tradition. It now has elements that are coming from other places.

iRJ: What are you currently working on?

MZ: Well we just came out with this record a couple of weeks ago and we’ll be in Chicago showcasing it in September. I’d love for people to check out the record and the show. Miguel Zenón represents a jazz musician who has achieved the American dream in a rather unique way. Bringing a highly personal perspective to music, Zenón has impressive credentials to his name already, and the future looks promising as well.

By Keli Denise and Jake Weisman