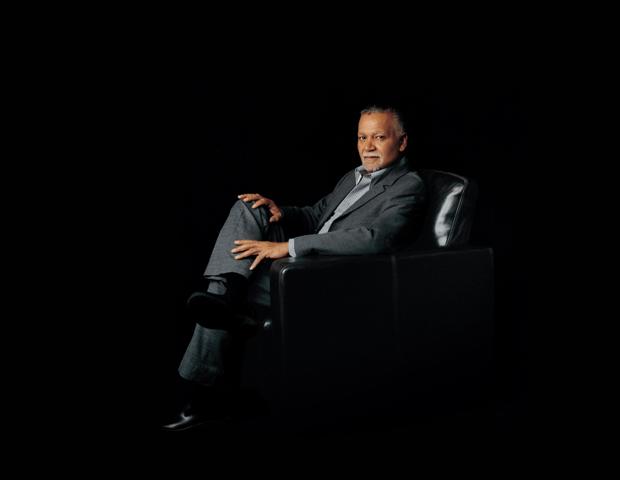

For thousands of years man has chosen a myriad of vehicles to chronicle history. Tales of birth, life, and death passed down by the village griot, the graceful fluidity of the Alvin Ailey Dancers paying homage to the human experience in movements, the intro, climax, and resolution of an August Wilson play lived out on stage. It is songs like legendary pianist, Joe Sample’s, “Street Life”, “In All My Wildest Dreams”, and “Soul Shadows”—sonically vivid images that become historical documents set to music. History has a way of helping us look to the past to shape today and give hope for the future. With nearly 40 albums to his credit as solo artist and founding member of the genre blending band, The Crusaders, Sample’s sound is birthed out of his rich history, which can be heard in every note and melody that not only illuminates his musical genius and but also affirms the responsibility he regards for his gift.

Sample is just as versed in his history as he is versatile in his music. Firmly aware and unapologetic of his identity, Sample’s music is a reflection of the heritage lodged deep within the African American experience. We were fortunate to speak with Joe Sample, who gave us a riveting glimpse of his story, his music and the work that keeps him inspired.

The Sound of Frenchtown

For Sample, his story began in the segregated enclave of Houston’s Fifth Ward called “Frenchtown”. This neighborhood was inhabited by black Creoles that migrated out of Louisiana in the 1920’s eager to escape searing racism for an opportunity to trade the sugar cane fields for the oil fields of East Texas. Musically, Houston became as rich as the black gold that spilled over from the abundance of oil derricks that proliferated the Texas landscape. “In the 1940’s I heard the big bands. It was on the radio, well pop radio. I heard the white music, which wasn’t entirely country it was Texas swing, which had a jazzier feel to it. There was gospel everywhere. There was this Texas mixing of gospel, jazz, and blues. It was a southeast Texas thing. I grew up in an area of the United States where we knew that jazz, gospel, R&B, blues, soul music were all distinctive parts of the African American experience. And that’s where I look. Even today, I think of myself as a folk musician. All of those ingredients are in me.”

According to Sample, that identifiable Texas sound—gospel tinged blues mixed with sophisticated soul—diminished with the rise of Motown and black pop music, but not before the sound of Ray Charles, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Professor Longhair, and local favorite, Amos Milburn made an indelible impression on a young Sample, who possessed great musical aspirations. “I grew up in a world of these black pianists were guiding us into a world of music,” he explained. Central to the sound of Frenchtown was the music of the Louisiana Creole. Sample’s people originated from an area near the Atchafalya Delta in Louisiana where zydeco music, a mash up of Cajun waltzes and Texas blues, was popular. Twice a month Sample could expect to hear “zydeco” legend, Clifton Chenier, playing “la la music”, as zydeco was originally called, during dances at his Creole catholic church in Frenchtown. He was influenced so much he created the Creole Joe Band that has toured internationally playing the music that connects him to his family heritage originating in the swamps of south Louisiana.

I Don’t March, I Do Music

As early as eight years old, Joe Sample was not only exposed to but acutely aware of the rampant racism that sought to paralyze the purpose of his promise. “I knew living here in Texas in the 1940’s, I would hear white politicians say ‘if you vote for me I promise you I will keep the nigger in his place’. I knew they were talking about me. Yet, I knew that I was black and my heroes were black men like Oscar Peterson, Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Clifton Chenier, yet I loved Brahms, Beethoven, and Bach. I knew it was racism and that I was being lied to.” Samples adolescent consciousness led him to search and read periodicals like the Pittsburgh Courier which empowered him and powered his music. “I wasn’t going to allow racist people to dictate to me or try to convince me that I was an inferior person. I got into this early and when the Civil Rights Movement began I was a 16 year old freshman at Texas Southern University. I made up in my mind then that I knew I wasn’t going to attend a Civil rights march, I was going to help my race out by becoming an awesome African-American musician”.

Sample’s 1990 album “Ashes to Ashes” which deals with the disintegration, lack of love and self-respect of both the black community and America” illustrates his position vividly and affirms his motivation to use his music to heal. And though racism seeks to weaken one’s identity and eventually lead to self-hate, Sample is unfazed even in the face of angst from his own. He recalled an experience in the 1960’s where he was confronted by what he calls the “brothers in the dashiki’s” who dismissed his complexion and mixed heritage as reason why he wasn’t qualified to play jazz, ultimately questioning his “blackness”. He shrugs it off as foolishness especially when considering the musical achievements to the African American experience from Duke Ellington, Horace Silver, and Sidney Bichet. Experiences as such even seem to reinforce his purpose. “I have looked upon my life and I have gotten a lot of criticism about what I have done and a lot of love about what I have done. I finally had to realize that I was blessed with a gift of being able to interpret with authority every sensitivity that is involved in the music of the African-American. I feel this powerful force in me that I know is the power of African American music.”

Often Sampled, Never Duplicated

Technology only enhances what already exists and should not wholly define one’s identity. Sample, along with celebrated pianists Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea amongst others, successfully fused the electronic keyboard into jazz marrying technology and the acoustic ultimately inspiring a generation of musicians including fellow Houston native, Robert Glasper. Interestingly enough, Sample’s acceptance of the electronic keyboard came by way of circumstance which led to convenience. After years of playing less than quality piano’s at clubs for years, Sample, so serious about his craft, quit live performances with The Crusaders. During his layoff, he became a high demand session musicians playing for everyone from Marvin Gaye, Miles Davis, B.B. King, and The Supremes. In the studio he realized the electronic instrument gave him some sense of control and a wealth of new innovative sounds. He then brought the studio to the stage eventually reuniting with The Crusaders and the rest is well, shall we say “history”. Sample’s embrace of the instruments like the Fender Rhodes and Wurlitzer created a signature sound for Sample that showed up on albums like The Crusaders Chain Reaction and Street Life, his 1978’s solo album, Rainbow Seeker which featured “In All My Wildest Dreams” sampled with mass appeal by Tupac Shakur’s “Dear Mama”.

Though Sample embraces technology, he knows it is not a replacement for his unique sound. “I have my touch. It’s an identifiable touch. How does that happen? It’s how my body is made and shaped, the size of my hands, the size of my fingers, and also what I feel inside of me. That all adds up to what the Joe Sample sound is.” Today Sample admits that technology may not only stifle the growth of many talented young musicians but young people in general. For Joe Sample, this is a problem that plagues the integrity of the music and the musician, especially when it comes to performing. “Nobody thought about the young musicians who were not having the opportunity to learn the skill of performing. There was a big void. In 1980 I ran into musicians who had never gigged before, who had never been on a bandstand before. That’s one of your biggest problems today,” he asserts. Today, Sample is attempting to fill that void in his role as an artist in residence professor at his alma mater, Texas Southern University. “What I’m doing at Texas Southern, I will be bringing these younger guys in the jazz clubs, on to bandstands, into performances. I have added an attractiveness and attraction so that young people will eventually enroll in the Texas Southern music department because they know I will be there teaching them how to be a ‘bad ass professional’ and when you play you have a smile on your face, enjoy doing it, and the audience will leave the auditorium or whatever venue you may be in feeling good about life.”

At 74, Sample is occupied with writing and producing music and has no plans to quit anytime soon at least in the next 20 years he asserts. He is currently writing a musical about the history of the black nuns that educated him in Houston and penning music for his new Creole Joe Band album as well as using his own story to give us a sample of what is to come for the next generation of musicians. The depth of Joe Sample’s history could not adequately be captured with words because his music embodies history. Just listen to his music and you will hear his story.

By Johnathan Eaglin