As the designer of over 700 products used all over the world, it’s definitely a slight to say industrial designer Charles Harrison is just a household name. As the mastermind of all of these concepts, the pioneer’s hand on them makes it’s merely impossible to not touch his influence. With his journey from freelancer to staff designer to the first African-American executive for Sears, Roebuck & Company, it’s even more difficult to not be inspired.

“It was a very lonely and uphill climb,” Harrison confesses. “I have to tell you that it was at a time in America when African Americans were not really welcome in corporate America. Most of us [African Americans] went there either because of some regulations that they had to satisfy in order to get government commitments and contracts. That’s how most of us were able to break through the barriers to get there. Even after that, there were many other people engaged in the assignments areas on various levels throughout the corporation and did not agree that we should participate in the mainstream of regular life. There were personal reasons developed over the years as they had learned that African Americans were not people who they wanted close to them in their business, socially or in any other way, and they held to those ideals. I had to learn early on I was in a hostile environment at all times. It took a while for me to put in place that I might run into resistance at any time, in terms of my career and my advancement within the corporation.”

With a BFA in industrial design from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where he received an honorary doctorate degree, and an MS in art education from the Illinois Institute of Design, Harrison professes his passion for education, which is why he decided to teach during the latter part of his career.

“What inspired me was my work for excellence and to help move all of us [African Americans] to another level,” he says. “I knew that we as a group had been strapped with the burden of negative expectations, and I wanted to break through that to prove we’re not all lazy and wanted to do anything at every level of excellence. I wanted to prove it for not only us as a group, but for me as an individual. I wanted to avoid being identified as the ‘one black rule that may be the exception’. You know, since that time, I’ve been labeled as another champion for our cause, as were some athletes like Jackie Robinson and a few others, who were able to perform and meet our expectations.”

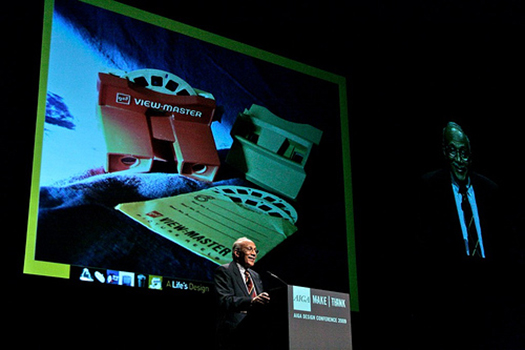

Charles Harrison designed the iconic Viewmaster picture viewer

Charles Harrison designed the iconic Viewmaster picture viewer

While Harrison was acknowledged and received several accolades for his accomplishments, he admits he does not own the patent of his designs. He also says this was not uncommon in his industry, and neither race nor skill level were factors.

“I’m sorry that I don’t have more recognition than I do; however at the time, the assignments were the recognition that came to be and I didn’t have a problem with it,” the designer comments. “It was common for all of us as designers, no matter what ethnic group we came from, to relinquish the title of authorship. That was customary of the profession of a designer. It was required to sign an agreement when you took on employment, whether it was a corporation or an independent design firm. I had to agree that anything I developed while I worked for the employer’s firm that my rights to ownership would automatically go to my employer. All designers were required to do the same thing. While I don’t own patents, many of those patents are in my name in the U.S. patent office [U.S Patent and Trademark Office]. The rights to the patent went to whomever I was employed by, which was Sears, Roebuck & Company. In reality, it is my property and I’m on record in the U.S. patent office. So, if I wanted to use it in writing or in a classroom, I think I’d be safe in doing it. Just because I don’t own the rights to the patent doesn’t mean I wasn’t recognized at one time or that I’m not registered any place.”

As an educator who taught at Columbia College Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago, Harrison says if designers in today’s industry needed to surrender their rights to their designs in order to gain employment, he would not discourage it.

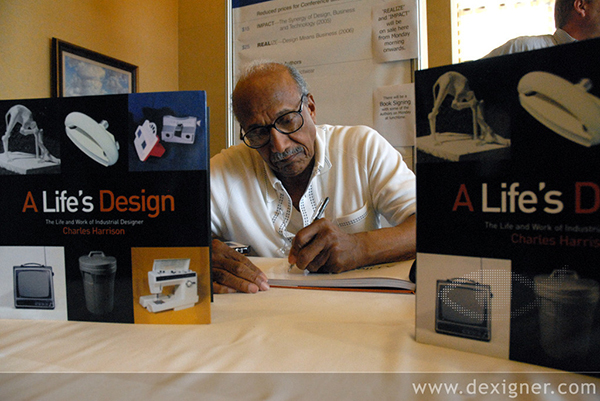

Much like a musician, a designer possesses the same approach to his or her work. The eye for detail, the desire for innovation and the goal of excellence remain paramount. Harrison used these concepts as he created his designs for products while he stayed true to the principles of providing the best quality of work. In his book, A Life’s Design: The Life and Work of Industrial Designer, Charles Harrison the designer and educator discusses his work and journey in the design industry.

Charles Harrison photo courtesy of dexigner.com

Charles Harrison photo courtesy of dexigner.com

“I didn’t go to sleep and wake up with a bright idea,” he says. “Almost everything I designed I was given as an assignment to design. I think it’s important to make a distinction between inventors and designers. Inventors deserve a lot of recognition and respect for what they do. Inventors come up with ideas and take those ideas to try to convince others they have something of quality or worthwhile that could be or should be produced, manufactured and sold. Designers don’t usually work that way. In my case, everything I was given was an assignment, whether it was a sewing machine or a hair dryer, in exchange for pay.”

Using both his creative and logical sides of his brain, Harrison said entering into the design process is also a problem-solving one since one has to accumulate as much information as possible and organize that data, including marketing strategies, before embarking on the design project. The materials used, how the product is mass produced and the cost are more of many other factors involved in the design process as well. For instance, Harrison says knowledge of a viewing area is critical information when designing the size of a television screen. Simply pulling something out of his head may not fulfill the needs of the product, he says.

As the innovator of hundreds of designs of products, the designer says he always gave his best in every aspect.

“I have no regrets and I enjoyed every minute of it, he adds. “Every project I worked on, I gave it 100 percent of my effort like everything else and did the best I could do with the time I had to develop it. Almost everything I designed I think could be improved and I’d like to be the one to improve it.”

The creation of the first polypropylene trash can earlier in Harrison’s career is what he credits as the design he’s most proud of. With the creation of a rectangular-shaped plastic container with wheels, the innovator developed a more cost-effective concept that was less noisy to handle than the steel one and was constructed with a durable material. Harrison admits it’s not until a product is sold in the marketplace and consumers respond that one realizes if it’s life-changing or if it’s a successful one, and this creation made its mark in history.

“With that product, we were able to raise the level of technology that was used to build that kind of product,” he adds. “No one had built a plastic product like that before.”

Harrison is a pioneer whose determination to be the best in all areas of life patented his place in history as an innovative designer. His concepts are used and recognized all over the world. As an educator and author, he spreads his legacy of excellence – in industrial design and in the broad scope of life.

By Iya Bakare