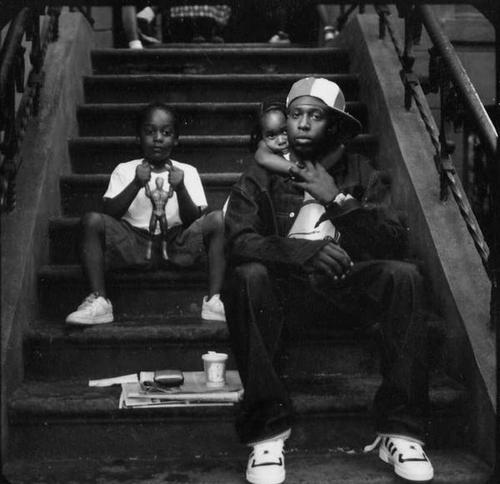

Talib Kweli has released some of the most seminal albums in hip-hop, such as Reflection Eternal with DJ Hi Tek, and Black Star his collaboration with Mos Def — among many other great releases. He appears as a guest with some of the cream of hip-hop, including Kanye West, Common and the late, great producer Jay Dillah. Artists like Jay-Z tout Kweli’s lyrical skills within his songs (and his eloquence), both on and off the microphone, which plainly are evident within this interview. The common, and opposing, aspects of hip-hop and Jazz within the changing climate of the music business are among some of the rich areas we explored.

iRJ: How would you define your music?

TK: I wouldn’t…I would leave [doing] that up to the journalists and the fans.

iRJ: Do you think “conscious” Rap artists are also poets?

TK: Of course, they are…that’s not even debatable. Whether or not people relate to what every Rap artist says, there is no denying that what they are doing is poetry.

iRJ: Why do you think Jazz gradually has waned in popularity while hip-hop has gone from being underground music to becoming the commercial success it now sees today?

iRJ: Why do you think Jazz gradually has waned in popularity while hip-hop has gone from being underground music to becoming the commercial success it now sees today?

TK: …In the way that Rap artists went toward entrepreneurship, Jazz artists focused on the canon of art, and making sure to protect the art. So, now, Jazz is the most revered, almost protected, music in America. People have more respect for Jazz than they do for anything. But, then young people don’t listen to it. It gets respected, but then it’s like you had a situation where I think the Jazz cats got so serious about the music that it ceased to be a young person’s music, because you had to have a certain amount of brevity, gravitas, depth, and experience to even break into the scene. I could be wrong because I wasn’t around [then].

But, especially to me, it seemed that in the 70’s when Jazz cats started breaking out, whether it was Herbie Hancock or Donald Byrd, when people started doing different types of things; adding a lot of electric music, and funk and soul to Jazz, there seemed to be a backlash from the Jazz community. I think when you don’t embrace what younger, newer artists are doing; then, you are going to kill the art form.

I think in hip-hop, I’m respected and revered by hip-hop purists. There are people who believe that my style of hip-hop is the only style of hip-hop that matters; that it should always be conscious, and it should always be sample based, and it should always be…. Even though I do that type of music; that’s what I enjoy; that’s what I am good at [doing]. I don’t agree with that assessment of how we need to move forward. I think the reason why, me personally, I’ve been able to do this type of music for so long is because I have always embraced new sounds. I have always embraced new, younger artists and new ideas. I think Jazz (at a certain point), in trying to be as pure as it could be, failed at [doing] that a little bit.

iRJ: If Jazz had to evolve to reach a younger audience, if it had to take a play out of the hip-hop playbook, what steps do you think it should take for that to happen?

TK: I think we are at an interesting time in music where Jazz wouldn’t even have to take a step out of just hip-hop. The same way Jazz dismissed younger newer sounds, what hip-hop has done is we have embraced corporate music, with the assembly line mentality, like “You’ve gotta have a hit on the radio.” That mentality has killed mainstream radio hip-hop, I believe. The artists that people are checking for in hip-hop, or any other style of music, are not the artists that the radio or corporations tell you [about necessarily]. The artists that people are checking for are those that blow up on YouTube, anywhere from Carly Ray Jepsen to the Harlem Shake to Macklemore or Ryan Lewis. These are things that started on YouTube, and made it to the radio. And, now, YouTube uses counts as spins.

TK: I think we are at an interesting time in music where Jazz wouldn’t even have to take a step out of just hip-hop. The same way Jazz dismissed younger newer sounds, what hip-hop has done is we have embraced corporate music, with the assembly line mentality, like “You’ve gotta have a hit on the radio.” That mentality has killed mainstream radio hip-hop, I believe. The artists that people are checking for in hip-hop, or any other style of music, are not the artists that the radio or corporations tell you [about necessarily]. The artists that people are checking for are those that blow up on YouTube, anywhere from Carly Ray Jepsen to the Harlem Shake to Macklemore or Ryan Lewis. These are things that started on YouTube, and made it to the radio. And, now, YouTube uses counts as spins.

If I were a young jazz artist, and I was trying to break out onto the scene, I would make my YouTube and social network so poppin’ that no one could “front” on it. Like Jazz virtuosos, or people doing improvisational Jazz, those are things that people don’t get to see “on the every day.” I would be taping every show, posting up clips of me performing on YouTube; talking to people who come on, and comment on the page; building my subscribers up. Because, if you do that for a year or so, consistently, you’ll get 100,000 subscribers. As soon as you drop a video, that means a 100,000 people are going to watch you within that week. And then you have a story that the industry can’t ignore. I think right now we see a time that we haven’t seen before where artists have more control than ever to “blow up.” And the ones who are large are the ones who are navigating that media properly.

A Jazz artist has to be aware of what happens in music trends. Like I was born in 1975…right? So, I have a certain way I like to hear music. I remember receiving the music that shaped me in the form of vinyl; then CDs, and then tapes. How people receive music, and what containers they receive them in, determines how they listen to it. So, right now, kids receive music through MP3s. MP3 is a compressed sound file so you are not even getting the richness of the song. [You don’t get] songs that sound warm; songs that have real music on them. You would be hard pressed to find something that has real instruments on it that’s doing well in mainstream radio. It’s almost like when you hear live, real instruments, it’s almost an old school sound. Even when you go see people perform, like Drake and Kanye, these people are performing with live musicians. But these guys are playing over live, hip-hop beats. They are playing over electronic music that is already there just to give it that “oomph.” You can be like Herbie Hancock who did an album that’s so good you can win a Grammy — even though no one in mainstream culture knew you had a new album out, which is what Hancock did a couple of years ago. Or you could [do] what Miles did, before he passed away, with what he was doing with Easy Mo Bee. Miles was always experimenting. But before he passed away, he was really delving into what was going on musically. I remember the stuff he did with Easy Mo Bee was on the radio, and it was a jazz artist doing it. But, that was 20 years ago.

iRJ: So where is hip-hop today?

iRJ: So where is hip-hop today?

TK: hip-hop today is firmly in the hands of corporate America, they’ve co-opted it. They use hip-hop to sell things, yet there is still the fuel that drives hip-hop’s fire. On the streets, kids are back to battling and rhyming. Kendrick Lamar just came out with a verse that named all the popular rappers that says he’s better than them, that he’s the king of New York. Just that one verse that was released on the Internet for free (because the sample couldn’t be cleared) made him the worldwide, international trending topic for the whole day. He sold two hundred thousand more records that day. Even though hip-hop has been co-opted, there is still a contingent of people that still care about the battling; the sport of it; the art of it. And artists like Kendrick Lamar exemplify that [fact]. The fact that he is also the number one rapper; the fact that he is very good at [doing] it is good news.

Can you tell us about the new, and upcoming, project you have coming out?

TK: I got my album Prisoner of Conscious I just dropped; I think people of all musical strengths would enjoy it. I got my label Javotti media. We are putting out an album of Reece, who’s a singer. We are putting out an album of Fleetwood Mac covers called Refried Mac — that’s the next project we are working on. We have an artist from down south, from Houston, called Cory Mo; a hip-hop artist. I am putting [out] an album with him on October 22nd; Refried Mac will be out [on] October 15th with Reece, the singer

Words by Willow Neilson