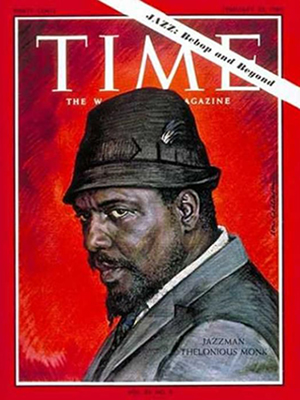

We will never fully understand the genius of Thelonious Sphere Monk, Sr. He embodied a particular brand of intellect that extended far beyond the scope of music. His was a way of life. Intelligently designed, it dictated the vivacious artistry we know him for, but also his most significant undertaking – fatherhood. Truly capturing the entirety of this man is a task that lies somewhere between daunting and futile. We can, however, through the eyes of one of his greatest compositions, gain a better perspective on one of jazz’s most important figures.

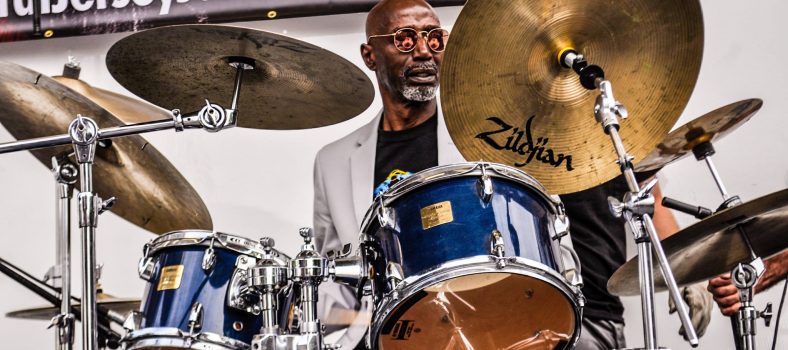

It is not easy being the offspring of someone so well-known, especially when you bear the same name. As much as it can be a gift, so, too, can it be a curse – the bittersweet enigma of a royal bloodline. T.S. Monk understands that better than most. As the son of Thelonious, he was privy to a world of which few could only imagine and far too many tried to speculate. This is Monk on Monk.

iRockJazz recently sat down to talk with T.S. Monk about his personal reflections of growing up Monk.

On growing up in the Monk household

TSM: The older I get the harder it is to say [laughs]. What I mean by that is on one level it was very, very normal. In the late 50s, Thelonious had his Cabaret Card taken away, so he was at home. My mother was the one working. Thelonious was doing the “Mr. Mom” thing. It was like any other guy that was out of work. He was at home taking care of the kids. On the other hand, there were a lot of guys coming to the house. But they were just “daddy’s friends.” It’s like if your dad has a friend named “Bob” and if your dad has a friend named “John.” Then you know your dad has a friend named Bob and a friend named John. For me it was Max [Roach] and Art [Blakey] and Miles [Davis] and it was Sonny [Rollins]. Contrary to popular belief, most of those guys, when they weren’t playing music, I remember them mostly talking politics. Jazz is a relatively intellectual endeavor and these guys are intellectuals. So it wasn’t like they were standing around talking about pentatonic scales and diminished chords continually. It’s like basketball players don’t stand around talking about bounce passes when they’re not playing [laughs]. So it was really a dichotomy for me, because Thelonious was a good father. And when he did go out, unless he was going out of town, he took me with him. I never felt like dad did something that I wasn’t involved in. I felt very close to him.

On recognizing his father’s genius

TSM: I kind of concluded that after a while. Of course, he was clearly different than everyone else’s dad. He was a lot more intense it seemed. From every indication I got from the people around him he was a lot more intelligent than everybody else too [laughs]. So I knew something was going on. Adults sometimes don’t know what they’re saying to kids, so if you have people saying to you, ‘Do you know who you your father is’? That’s a crazy question for a six year old, you know. I mean what do you mean ‘Do I know who my father is’? He’s my daddy. So that was very confusing. Of course, they were referring to his musical accomplishments. But I didn’t know anything about that. All I knew is that my father played the piano. Most of my friend’s fathers drove buses and were mailmen and did things like that. So I knew he had something going on. But in terms of trying to convey the magnitude of his genius to a ten year old it’s a silly thing to even try to do.

On the pressures of being the son of Thelonious Monk

TSM: The fundamental ideology that was in his music was a part of him. And that was that everybody is an individual. For a lack of a better term, what the musicians of his era said was ‘Play your own shit’. He removed the shadow thing. Once the shadow thing was removed, I was allowed to just be myself and grow up and run around. There was no requirement for me to be involved in music in anyway. It was about being involved with him personally as a father not as this genius that everybody else was talking about. That was very liberating for me. It allowed me to not realize who my father “was” until I was about 19 years old. Now as I got older, it was clear to me that he was important on some level. But even as a teenager it’s hard to perceive. It just doesn’t sink in really. By the time I got into my 20s I realized how important he was in a historical sense. But as a kid he kept all of that stuff away from me. He took me aside when I was about 8 or 9 and told me that there were people that were going to tell me that I was supposed to do this and supposed to do that because of him and don’t go for it. He said, ‘You do what you want to do. Be who you want to be’. That’s the exact same thing he did musically and the exact same thing he said when mentoring Miles and Sonny and [John] Coltrane and Bud Powell. It wasn’t simply his music; it was his life and his mindset.

On criticisms of his father

On criticisms of his father

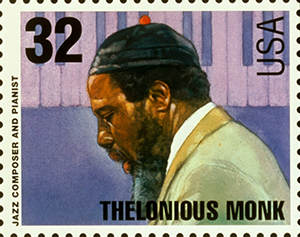

TSM: Most of it, you have to understand, took place really before I was born. By the time I came on the scene in ’49, he was clearly moving into his primary influence as the father of modern jazz. By the time I was 9 years old, he had won the national critics award. By the time I was 13 years old, he was on the cover of Time magazine. So I wasn’t privy in a firsthand sense to the beating he really took as a young artist. They all lived that. It never really had an effect on me. Thelonious had a “water roll off my back” mentality. He told me not to even read what they write because the same cat that loves you this week will say your stuff’s not happening next week. The whole family was like that. In the early 50s, Thelonious made a record called The Unique Thelonious Monk and on the cover of a record is a stamp. Riverside Records actually printed up the cover as a stamp and a few fans even mailed them to us [laughs]. The reason I bring that up is because I distinctly remember all of my older cousins and aunts and uncles talking about ‘One day they’re going to have a real stamp for Uncle Thelonious’ and in 1996, I stood with the Postmaster General as he unveiled a commemorative stamp for Thelonious Monk. It was the internal fortitude within that family that also protected me against the criticisms of Thelonious.

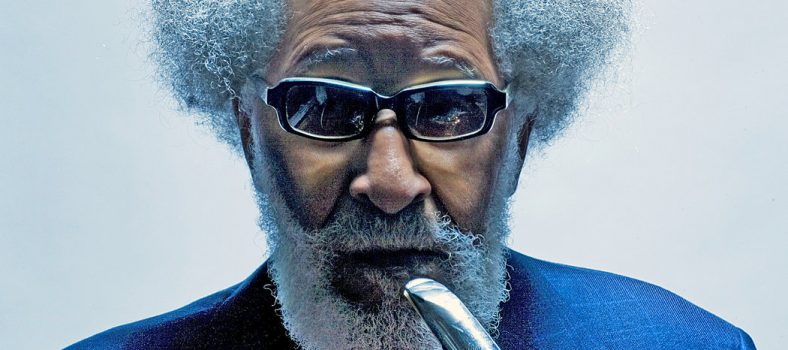

On his father’s contribution to the Civil Rights Movement

On his father’s contribution to the Civil Rights Movement

TSM: Bebop was viewed as left wing music. This is something we forget. There was a clear political component to bebop. They were trying to play music that was confusing to the greater society. The blackness of the music and the blackness of the artisans themselves was part of the movement. That’s why the white intellectual, particularly Jewish intellectuals, at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement, were all friends with the jazz musicians. I’m talking Allen Ginsberg. I’m talking Jack Kerouac. I’m talking Lenny Bruce. I’m talking Eugene Smith, the photographer. I’m talking Bertrand Russell. And where did they hang out? They hung out in the Five Spot. They hung out in the Village Gate. They hung out at all of those little clubs uptown, because that’s where the energy was. Martin Luther King spoke at the jazz festival in Germany because of what was being said in the music. Max Roach’s “Members Don’t Get Weary,” or Rahsaan Roland Kirk “Volunteered Slavery” – the message of civil rights was being spoken and played on the actual records themselves. With Thelonious, he represented, within the musician community, who we are. Thelonious was the one they couldn’t change. He was a black man and that was that. When the white man basically said ‘Listen, y’all are gonna have to stop putting a funky beat under your music so we can compete with this rock and roll coming from Europe,’ Thelonious didn’t go for it. The art always reflects the politics of the time and bebop clearly reflected the turmoil and the intellectual acumen of the 1950s and 1960s.

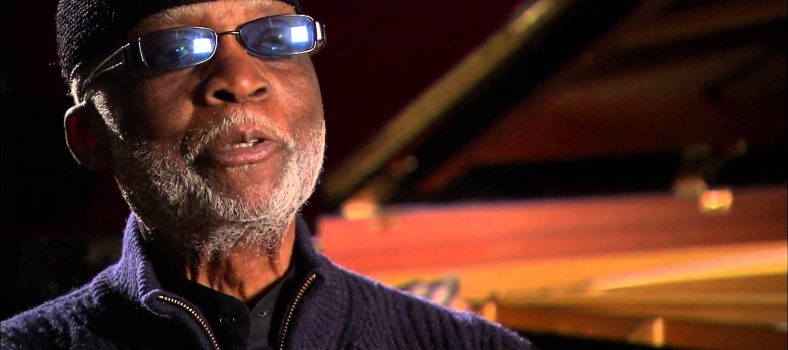

On dealing with his father’s declining health

TSM: It didn’t affect me or my mother or my sister or anyone else in the family in a negative way other than the fact that Uncle Thelonious was ill and that was a drag. See, we always knew what his problem was. Eventually, the public found out that he was bipolar. Initially, the public just thought he was another casualty of the jazz wars of the 1950s that took away everybody from Bird to Bud to Booker Little and so many, many more who abused themselves. But Thelonious hadn’t done that. So we never viewed him that way within the family. We knew that he was ill. So as his health diminished, we just picked up the slack. I remember that myself and my mother and my sister never had a conversation about ‘Oh dad can’t make money like he used to. What are we going to do?’ That was never a topic of discussion. We knew that this was a man that would do anything and everything for his family if he could and so it was time for us to take care of him. I got involved on the business side so that his money would stay straight enough so that he wouldn’t have to work. He had worked for 35-40 years. That was enough. Again, everything around Thelonious was unique and his uniqueness was instilled on to the entire family on both sides. We just all knew who he was. He was precious to all of us. So the only affect it had was when someone close to you gets sick and you just want to take care of them.

From the life of T.S. Monk, we learn the true nature of a historic figure whose own narrative is complicated at best. For many years, we heard the stories of an eccentric artist taken by the ills of a decadent music. But like Monk told his son, you can’t always believe what you read. The truth is that Thelonious Monk was much wiser than the people criticizing him in the first place. He understood what they did not. And that was that everyone is an individual with their own story. He taught that to his pupils, but most importantly his children. While many dismissed him as “crazy,” perhaps they should have been taking notes instead. Looking at the successes of his son, I would say that it’s not such a bad idea.

By Paul Pennington