There will never be another George Clinton.

Don’t take that as the customary regurgitation of hyperbolic praise typically found in a piece like this, because, honestly, I’m not even talking about music right now. We already know his place in history – Funkadelic, Parliament, P-Funk, whatever. We’ve listened to Maggot Brain three times just this week (…and if you haven’t shame on you). We’re already past that. For today’s purpose, I want you to think about the man himself. Think about the hair, the outfits…those damn album titles. Now ask yourself, “What would I expect from a conversation with George Clinton?”

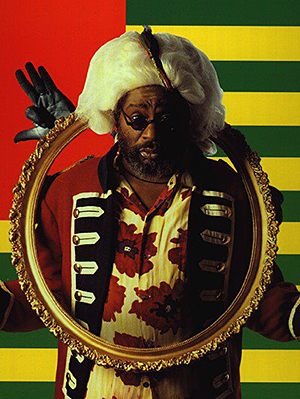

If you’re anything like me, you imagined eccentric wordplay accentuated by the sway of Technicolor hair extensions. It’s odd, sure, but wholly understood within the nearly mythical context of the man, George Clinton.

But you know what’s even stranger than that? Reality

Somewhere buried underneath this sartorial decadence is an individual built of sound reason and thought-provoking social commentary. Don’t let the hair fool you. George Clinton is more self-aware than any of us could ever hope to be.

iRockJazz recently sat down to talk with George Clinton about his expansive career, both on the stage and behind-the-scenes.

iRJ: In the beginning you began as a barber, correct?

GC: First, I started out singing, you know, 14-15 years old. Everybody had a group in Newark, Brooklyn, Harlem. When I came out in the era of doo-wop, everybody sang and when you sang you had to get your hair done. So we started out doing each other’s hair. And I immediately got a job in the barbershop doing processes which was the big money maker in the 50s and through the 60s.

iRJ: So, you started out doing doo-wop. When did your work with that sound taper off and what was the timeline for each band you created after that?

GC: The doo-wop group was The Parliaments. By the 60s we had a hit record, “I Wanna Testify.” The Parliaments didn’t get another single right behind it, so they put us back into that perpetual thing of “looking for a hit.” So I decided I wasn’t going to be like that. We couldn’t use the name Parliament because the record company went out of business, so we made a group called Funkadelic, which was our band from Planfield. It was a bunch of young kids that played bass guitar and drums. They became Funkadelic and we became their backup singers. So, in the meantime, we got the Parliament name back and did another record for Holland-Dozier-Holland for Motown. It didn’t do anything. But now you had Parliament and Funkadelic. Bootsy [Collins], who used to play with us in the early 70s, we made his own group, Bootsy’s Rubber Band. We took the girls that were singing background with us and we named them Parlette. The other two that played with Sly [Stone] – Lynn [Mabry] and Dawn [Silva] – we named them the Brides of Funkenstein. We took the horn players who were also with Bootsy and James Brown –it was Fred Wesley and Maceo Parker – and we named them the Horny Horns.

GC: The doo-wop group was The Parliaments. By the 60s we had a hit record, “I Wanna Testify.” The Parliaments didn’t get another single right behind it, so they put us back into that perpetual thing of “looking for a hit.” So I decided I wasn’t going to be like that. We couldn’t use the name Parliament because the record company went out of business, so we made a group called Funkadelic, which was our band from Planfield. It was a bunch of young kids that played bass guitar and drums. They became Funkadelic and we became their backup singers. So, in the meantime, we got the Parliament name back and did another record for Holland-Dozier-Holland for Motown. It didn’t do anything. But now you had Parliament and Funkadelic. Bootsy [Collins], who used to play with us in the early 70s, we made his own group, Bootsy’s Rubber Band. We took the girls that were singing background with us and we named them Parlette. The other two that played with Sly [Stone] – Lynn [Mabry] and Dawn [Silva] – we named them the Brides of Funkenstein. We took the horn players who were also with Bootsy and James Brown –it was Fred Wesley and Maceo Parker – and we named them the Horny Horns.

iRJ: One of your most popular Funkadelic albums, Maggot Brain, had a very strong rock influence. Was that difficult for people to accept being that rock was beginning to be considered “white music?”

GC: Yeah. That one and Free Your Mind was really psychedelic. But the thing was Chuck Berry, Elmore James, Muddy Waters – they made that music first. It was just that over a period of time the radio had separated it. Blues was white and rock and roll was white and R&B and soul music was black. And even that would change. It don’t really matter what you’re doing. The media tries to pigeonhole it and carve it out for themselves. We were all of that. We were doo-wop. We were Motown. We were psychedelic. That’s why we called ourselves Funkadelic. We played all kind of music. So, yeah. We were too white for black folks and too black for white folks. But the people that liked us, they stayed with us no matter what. To this day we have black, white, kids, adults – it doesn’t matter. We have all the different people because we don’t fit in any box.

iRJ: When thinking of your involvement within the funk movement, the vocabulary stands out. How did all of the clever wordplay come about?

GC: When we first started, knew that talking street talk always worked, because it’s in tune with the culture at the moment. On the radio, DJs were doing most of the talking. And no matter where you went, that was the sound of the city. So, we took that DJ sound and used it in our music – like people would be talking in the streets. Basically, it was drug talk. Like ‘Make my funk the P-Funk,’ ‘Uncut,’ ‘The bomb,’ you know. We talked about the funk being like dope. Hip-hop came along and got the message and that’s why they started saying, ‘That’s dope’. They’d sample the dopest parts of P-Funk records and use it like cloning. You can clone something new with a single cell. Well, you can make some new dope music if you have a little bit of P-funk. Take a little bit of the beat from “Atomic Dog.” If they mixed it in then that makes dope. Usually you take the dope and put mix in it and cut it. But when you put P-Funk in it, you get more dope. [laughs]

iRJ: You have an interesting style, between the colors and overall attire. What brought that about?

GC: You know, it’s weird too because I’m actually colorblind. Once we started doing the psychedelic thing, we just got the silliest stuff. I used to wear the sheet. I use to wear the diaper. And then from there, we’re hair stylists so we knew how to do any kind of style we wanted to whether it was ugly or nice. When we started to go crazy, we decided to really go crazy. And we just put any and everything we could put on to be absurd because we knew we had this serious music – serious funk, serious bluesy-gospel, serious psychedelic. The music was good. It didn’t matter what we wore.

George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic photo by William Thoren

George Clinton and Parliament Funkadelic photo by William Thoren

iRJ: In the latter part of your career, you’ve talked about not being properly compensated when other artists sample your work. Talk about that.

GC: I found out later that the people that are hijacking the royalties are at such a high level of corruption. We’ve been to the senators and Congress and we’re getting ready to put out our own press release on all the stuff that’s going on. The New York Times and ABC were getting ready to do an exposé. They both filed a claim to have these documents unsealed – thousands pertaining to all the samples P-Funk writers. But for some reason, they’ve shut it down. WXYZ out of the Detroit said that they didn’t want to hurt the opening of the Motown musical. My beef wasn’t with [Motown], even though I had lots of songs with them that I never got paid for. My beef was with Bridgeport Music. Those are the ones that are not paying. The artists pay for the songs that they use. The rappers they pay lots of money, but we never got any of it. And now they’re actually trying to change the law for copyright recovery. We’re right now getting ready to do our own exposé. You’ll see that in a minute.

iRJ: How has this fight affected you personally?

GC: It has held up a number of records that we’ve tried to put out. Every record company out there has sampled this stuff and they’ve gotten together in a conspiracy to stop not having to pay for it because it means a lot of money to a lot of people. That pretty much has an effect on us that we can’t even get a record out. We’re getting ready to do a reality show with my family. My grandkids – all of them are entertainers and they’re trying to learn the business. They’re trying to learn what’s going on with the copyright issue. So it affects everything we do because people are scared. Snoop [Lion] was the first to come along and say that he was going to help us. Because it involves all of them too. Most of the artists from the 90s are going to feel the pressure of them not wanting to pay them all that money that they made on those records. You’ll find all of them with lawsuits any minute because they made too much money and that system doesn’t want them to give it up.

iRJ: Most artists find different levels of success throughout their careers. How have you managed to keep yourself consistently relevant for all of these years?

GC: Whenever you hear older musicians or parents say, ‘Damn! That ain’t music! I wish they’d stop playing that’! That’s the music that I’d go learn about. That’s the music to me that’s going to be the next music. You can tell the next music that’s going to be because the older musicians don’t want it to come and the parents don’t like it either. So, when hip-hop came along you can tell it was going to be the shit because too many people hated it. Kids love to do what you don’t like them to do, so, they‘re going to make it right, even if they don’t care about it at first. But when they hear you bitching about it, they’re glad to get on your nerves.

iRJ: Considering you’ve been a part of pop culture for several decades now, what do you want your legacy to be?

GC: I want to keep making musicians aware of the business part of this. Learn about the copyright and all the money that is still there, even when you don’t think a record is a hit. I want to be able to say that after all we’ve done musically that I motivated awareness of how the big corporations – all the way to BMI, ASCAP, the US Library – how all of that stuff can be corrupted and is corrupted; all of the policies on congressional laws of copyright, all of that is falling into the hands of lawyers. I want my legacy to be the exposure of all of that.

It’s been said that perception supersedes reality. The case of George Clinton only solidifies this notion. His persona is larger than life, an appearance that belies a man craftily navigating the legal intricacies of the music industry. His artistic influence can be found in countless artists from funk to hip-hop and that list only continues to grow. However, when we ultimately look back on the legacy of George Clinton, the most endearing part of his story may be what he has accomplished outside of that anomalous façade – dressed only in a keen wit and sharp intellect.

Grand master of Parliament and Funkadelic and commander of the cosmic P-funk mothership George Clinton has launched a more terrestrial campaign as part of copyright group Flashlight 2013 to secure the rights of musicians who have failed to receive royalties for their work.

By Paul Pennington