If you were to ask two-time Grammy-Award winner jazz trumpeter, composer, and social activist, Hugh Masekela, how he would categorize himself or his music his response would be, “I am just a musician from Africa who immersed himself with everything to do with music.” From growing up in South Africa to befriending such musical greats as Miriam Makeba, Harry Belafonte, Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis who he considered family, Masekela is a legend in his own right.

Fifty plus years and 44 albums later Hugh Masekela has made an indelible mark on jazz and popular music. Known as one of the vanguards of African music, it was the release of his 1968 Grammy-Award winning Grazing in the Grass album, and headlining the 1968 Newport Jazz Festival that shot him to stardom.

Masekela’s collaborations with a host of jazz and popular music greats have forever secured his place as a jazz great who is currently touring with an ensemble that is attracting new fans to his musical style. iRock Jazz had the pleasure of interviewing Masekela where he talked about his music and its influences, while growing up in South Africa and the history as well as living in America.

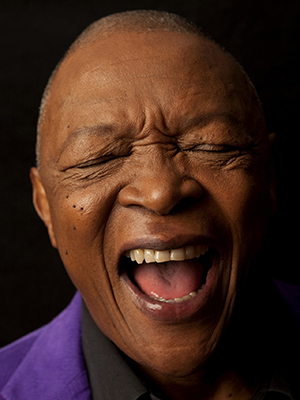

Hugh Masekela photo by Mark Shoul

iRJ: How would you define your music?

HM: I don’t define it, because I don’t have to define it. Understanding or reception of music comes from the ear and as soon as it becomes intellectual it is unrelated to the original content or whatever it is.

I’ve been a musician since I was a child, I started to feverishly be obsessed with music from the time I was two or three-years old with the gramophone and I lived for that. As children when I grew up there was no television, so children sang a lot in the street and we played games.

I grew up in an area that was the hub of migrant labor from all over South and Central and East Africa – the weekends were kind of a pageantry where you could see the different ethnic groups doing their traditional things, and we had original hymns in the missionary churches that were native languages and we had great choral composers school competitions; so I am just a potpourri of a cross section access to universal music and I always lived in that world.

When the word jazz came out I was already a teenager when it became popular. But the word jazz came from white critics and so-called white analysts of music. It came from the same source that Rock came from and fusion, urban adult and all those other categories but I’ve never lived in those categories. But labels don’t come from musicians I met Louie (Armstrong), Dizzy (Gillespie), Miles (Davis), Ella (Fitzgerald) and Sarah Vaughn and worked with all those people and I never heard them say we play jazz. This here is a marketing word. You know what the original meaning of the word jazz is right?

iRJ: What is your version of the word jazz?

HM: Jazz came from brothels. To jazz is to have sex. So people went to jazz joints because they were brothels. And rag time piano – rag time, you went to a jazz joint during rag time that’s when your old lady was on the rag. People don’t understand where it comes from. I never want to dignify those words by saying I’m part of it, because it has nothing to do with the originators of all of this music.

iRJ: How would you categorize yourself, just a musician?

HM: I’m just a musician from Africa who immersed himself in everything that has to do with music. I don’t have to analyze what I do. Musicians don’t have to analyze what they do. They are better off spending time doing what they have to do than analyzing it.

iRJ: During the whole political movement in South Africa did that change or effect the way you played or the music that you composed?

HM: No, I came from people who were at war with oppression. I grew up in boycotts. We all grew up in boycotts, marches, rallies, demonstrations and even massacres. What people don’t realize is that our history we’ve been fighting – until 1994, we’ve been fighting for almost 400 years.

Hugh Masekela photo by Mark Shoul

iRJ: Why did you leave Africa ?

HM: I left Africa to get a musical education. I first went to London for five months; I was helped by a priest monk who got me my first trumpet, and who was deported from South Africa. An English monk, Father Hadelston, who when he got back to England started an anti-apartheid movement that really spread throughout the world. He got me my first scholarship to Guildhall School of Music and then Miriam Makeba was a childhood friend who had really exploded in the States together with Harry Belafonte they brought me to Manhattan School of Music.

I came originally so I can get a higher education and have access to the kind of teachers that people would idolize like Louie Armstrong, or Dizzy, Miles or Clifford Brown had access to. My plan was to go back to South Africa in 1963 when I graduated from Manhattan School of Music, but by then everybody I associated with was banned from South Africa including Miriam and Harry and their records were banned, there was no way my passport was going to be renewed.

So I stayed 26 years longer than I planned to stay away from South Africa. But during that time I got involved with fighting injustice universally, not just in South Africa, because my mentors were people who figured that if you came from a people who were resourceful and a success and you didn’t give back a part or to them then you needed your head examined – that’s how I grew up. But it wasn’t because I was in to politics.

iRJ: What was it like meeting your iconic musicians like Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis? And what did you learn from them?

HM: Well they didn’t look at themselves as icons or legends, they were givers. They wanted you to feel a passion for music. They wanted to find out how best they could help you, to guide you and for you to be as good and where they had landed.

By 1968, I had vindicated the beliefs of everybody who put their beliefs in me because in 1968 I headed the Newport Jazz Festival series all over the country that’s a dream that I never dreamt. It’s just a gift that came to me because I worked hard on my craft and a person like Dizzy Gillespie, was like a foster father to me. And a person like Miles was a dear older brother, and many other people were key for me to achieve my aspirations. I worked very hard for them to vindicate their belief in me.

Hugh Masekela photo by Brett Rubin

Hugh Masekela photo by Brett Rubin

iRJ: Was it difficult for you as an African coming to America to work with African-Americans or Black musicians at that time or did they embrace you automatically as just a musician?

HM: I was a scholar of music. I was also highly educated academically. So I wasn’t exactly naïve when I came to the States. I knew everything about America to a great extent and more than most Americans. Because I came from a home where we weren’t only home-schooled a lot but my father and mother insisted that we become voracious readers and that we know everything about the world. I was a scholar of not only music but I could tell you where Count Basie came from and the name of his parents – I also knew everything about Joe Lewis and Sugar Ray Robinson, Battling Siki and Jersey Joe Walcott and all of those people. We knew everything about Ethel Waters and Ella Fitzgerald, Eddie Rochester, Louie Armstrong; we were scholars especially of the African-American world.

So I didn’t have to adjust. I think what I had to adjust to were the little freedoms that were there, because when I arrived in America in 1960 of September Richard Nixon and John Kennedy were campaigning for the presidency and that’s the only thing that I’d never seen in my life before – was a political campaign because we didn’t participate in that in South Africa.

iRJ: Where is your music going today?

HM: I don’t analyze what I am doing. I don’t know if you’re coming to see us, but if you do, you’ll find the group – there are six of us on stage: the percussion, a drummer, a bass play, a guitar player, a keyboard player and myself – we all sing together. They’re outstanding musicians and they are virtuosos in their individual instruments and our live performance shows off not only how good we can play instruments but what an outstanding ensemble we are playing together and outstanding soloists, and at the same time we keep it entertaining. Every concert we play, the audience doesn’t want us to leave.

iRJ: What are you advocating for today ?

HM: My biggest obsession is heritage restoration in to African society. We’re the only society that imitates other societies, other cultures. We come from a cross-section of a people with amazing pageantry, amazing musical content, design couture, dance, architecture, poetry, oral history; all of those things are missing in our lives and when people look for Africans they can’t find them so they rather go see the animals and geographical sights because Africans have been placed internationally in a position where they can’t afford to show off their pageantry and the fine contents of their traditions because those things were not only killed with slavery and conquest but also urbanization and misinterpretation of education, advertisement, television and religion. All of those things have led us to feel and believe to a great extent that our own heritage is pagan, heathen, backwards, primitive, savage, barbaric and yet, we have one of the richest continents of any society in the world as far as heritage is concerned, not only artistically but in all other walks of life.

I’m also very heavy in to health not only as an interventionist, with things like substance abuse and terminal diseases but also exercise and I’ve been doing Tai-Chi for almost 10 years, I walk, I swim. I’m pretty fit for a 74-year old person.

iRJ: What would you like your life’s legacy to be?

HM: I’m not that presumptuous that I can leave a legacy but it would be fantastic to know that that I was part of the initiative to revive all of the things that I’m talking about that should be revived in our lives. If I can be part of the beginning of the initiatives in that direction than I will know that when my children – my grandchildren especially, grow up and they ask them who they are they won’t say, ‘We used to be Africans long ago’.

By K. Gerard Thomas