Brooklyn, NY. Saturday, October 6, 2012. It’s 8:45pm just outside the doors of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Auditorium, located on the third floor of the Brooklyn Museum. Many people congregated there to witness a celebration of rare and innovative music. The auditorium was located on the third floor and in order to reach it, the concertgoers had to walk through an exhibit called Egypt Reborn: Art for Eternity, a long term gallery installation that presented priceless African relics. The walls are adorned with gold and reminders of an ancient time when the pharaohs and inhabitants of the North African country were the envy of the globe, thanks to their innovative architecture, imagery and regality.

Each and every one of those who gazed upon the gallery had no choice but to feel fascination and inspiration from these tombs that encased kings. The women were immortalized in these alabaster carvings and sculptures that presented them as both nurturers and rulers. Finally, when the eager souls filled the hall’s 415 seats, they were ready to bask in another priceless African artifact the music of one Betty Davis.

Conceived by Brooklyn singer Nucomme Davis-Walker, “Betty’s Story” was a multimedia tribute to the under-championed singer/songwriter who had used funk to empower and liberate her listeners and herself. “Betty’s Story” was a feast to the senses, which featured an aural narration of her career, video collages of news clippings and album covers, a raucous five-piece band and alluring exotic dance, provided by the Brown Girls Burlesque troupe.

In between the spoken dialogue was the true legend as the robust, confident Nucomme, who decisively and convincingly belted out songs from Davis’ catalog, like the defiant “Nasty Gal” and the driving hedonism of “If I’m in Luck I Might Get Picked Up”. The crowd took it all in, rocking their heads, clinching their fists and biting their lips as the curdling bass injected its way into their veins, the burlesque dancers occupied their eyes and Nucomme’s voice dominated their minds.

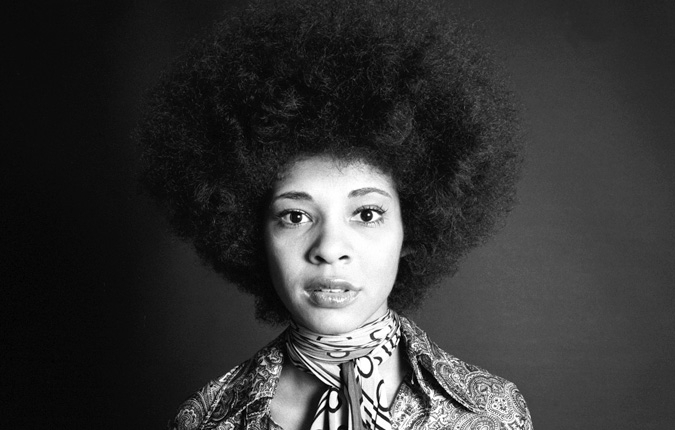

In the end, however, it was their souls that got the ultimate workout, which of course was their rationale behind attending the event in the first place. Davis’ assertive, unfiltered artistry had a lingering effect on each of them, prior to their decisions to enter the Brooklyn Museum. All the while, projected above the performers were images of Betty at several stages of her career, as an exuberant young model that made the road easier for Black beauties like Iman, Naomi Campbell and Tyra Banks, and as a rough singing sexual dynamo who paved the way for artists like Millie Jackson, Rick James and Prince.

No matter in what incarnation, there she was, high above the stage, her flawless fair skin, her shining pouty lips, with that proud and natural afro, like she was carved from a piece of jade. When you look into her eyes, you see a trailblazer, but behind them was just an artist who only wanted her music to be heard; an artist who used her sexual energy on stage and wax to fulfill her need to simply write songs.

When it comes to the influence that Betty Davis bestowed on music, her individual work is always an afterthought when held up against her lasting impression on former husband, legendary trumpeter Miles Davis. Fact about it, whenever her name is mentioned in print, it’s immediately followed by “ex-wife of Miles Davis”.

Though only married for one year, that period from 1968-1969 was the catalyst for the most significant transition in the history of Jazz. Betty introduced Miles to the sounds and people who were leading music to new heights – James Brown, Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix. Miles became enthralled not only with the music, but to their style, their individuality and how their music ignited the black audience in a way that Jazz could not. Their relationship spawned a string of recordings in which Miles incorporated the influences of Funk and Rock with Jazz, ultimately defining Jazz fusion and changed the landscape of music with Bitches Brew (1969; originally titled Witches Brew until Betty suggested Bitches), A Tribute to Jack Johnson (1971), Live-Evil (1971) and On the Corner (1972).

Miles’ sense of fashion dramatically altered as well, ditching his Brooks Brothers gray suits with velvet jackets, denim flairs and multi-colored scarves. Even though she inspired a result of that magnitude, Betty was not content with being solely Miles’ muse, and in fact, contends that the transference of inspiration was indeed mutual, as Miles exposed her to the finer points of Jazz, which she felt was a less exciting genre. “I think we were both exposed to different kinds of music and I think that affected the music that we made [respectively]”, Betty said.

Such an exchange of ideas manifested itself through a collaboration between the husband and wife on record. The two recorded songs for an album that included drummer Tony Williams, tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter and bassist Billy Cox! “It was really Miles’ idea, not mine,” she recalls – “He did all the arrangements and got the musicians together for me. I remember one song was called “Politician”, and it was an Eric Clapton/Jack Bruce song. I can’t remember the other ones; I haven’t heard [the records] in such a long time. It was done in the ‘60s, before I ever recorded.” Unfortunately, the album was unreleased and remains so to this day. The masters of those sessions are currently held by the Miles Davis estate. “That would be very good,” Betty expressed.

The extent of how Betty Davis’ existence changed American music goes so far beyond her influence on Miles Davis, and it would be an insult to even describe it as a “ripple effect”, insinuating a pebble dropped into a pond. Her impact has been so severe that it warrants the quantification of a “tsunami effect”, more of a meteor striking the Pacific Ocean.

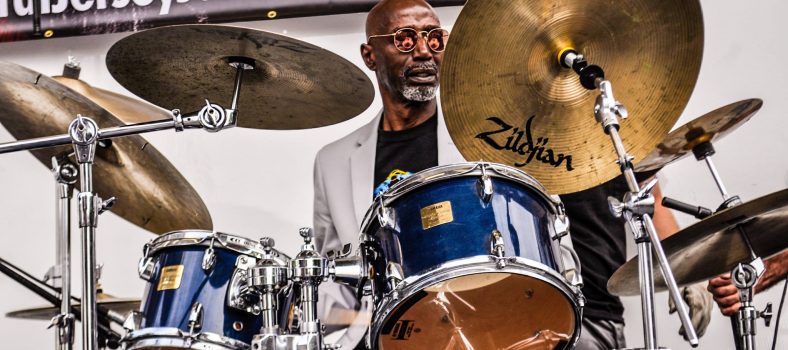

Davis back by her North Carolina-based band and her backup singers, “The Ladies”

Davis back by her North Carolina-based band and her backup singers, “The Ladies”

Davis is arguably the prototype of every single black female vocalist of note in the 21st century. Beyonce Knowles may have famously credited Tina Turner for her inspiration on stage once during the Grammys, but if you watch closely on stage, watch Knowles’ stalking demeanor, Rihanna’s scantily enticing wardrobe, Nicki Minaj’s defiantly colorful fashion sense and the collective attention spent developing their wildly sexual auras. It’s evident that Davis predates each and every one of them. She achieved that sexual freedom through the inspiration of the music of her childhood.

During her early years in the 1940s and 1950s, spent in Durham, N.C. and Homestead, Pa., Davis absorbed the down-home abandon of the blues. “When I was that young, I was really listening to what my mother played on the record machine,” she explained. “It was really the blues – John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Lightin’ Hopkins, Koko Taylor, Big Mama Thornton.” Soon, the music had called to her, as she began writing songs as early as age 12. As time passed, the seeds for what would become her signature sound became clear with each new influence. “I think when you take the artists that I was listening to in my teens, my early 20’s – Sly Stone, Otis Redding, James Brown, Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin, I think it was integrated into blues and what my music transpired into.”

Davis’ artistry was born out of the tradition of singers like Bessie Smith and other female blues queens who embraced their desires and libidinous potency. “Blues singers owned their sexuality, and I think that was an important lesson for Betty,” exclaimed Nucomme of her hero in an interview with the blog Open: An Erotic Journal. “Blues singers like Lucille Bogan were not coy about singing about men humpin’ them dry.”

However, unlike Smith and Bogan, Davis had no intentions of singing about such exploits. In fact, she had no intentions of singing at all. “I really started off as a writer, so I didn’t approach my art as a singer; it was as a writer.” Davis got her first big break as a writer age 23 when The Chambers Brothers recorded and released her song “Uptown” in 1967. She spent the late 1960s looking for a deal to become an in-house writer/composer for a record label, and actually came dangerously close to a legendary opportunity. “I had written some songs for a group called the Commodores, but they weren’t signed to Motown at that point; they were looking for a record deal,” Davis recalled. “Their manager, Benny Ashburn, approached me and I decided to work with them. However, when they got the deal with Motown, I couldn’t work out a writer’s deal with Motown. So, I was left with all of these songs and that’s how I got the deal with Just Sunshine.”

It was at Just Sunshine Records that the planets aligned and ignited the major turning point for Betty’s approach to her art. Michael Lang, the label’s West Coast representative, who heard her voice on the demos she’d recorded, (originally intended to be distributed by the company to other artists and shared with a Just Sunshine executive) thought Davis sounded like “a female Dr. John.” In 1972, Betty signed a deal as a recording artist, and became a singer, as she described, “by accident.” How fateful that some of life’s greatest gifts are born out of chance. End pt. I

by Matthew Allen