When one considers great jazz performers and pianists, names such as Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, and Art Tatum, come to mind, and one day Wynton Marsalis’ young prodigy Aaron Diehl may be named among those greats.

Born in Columbus Ohio, Diehl began his musical journey as a student and 2007 graduate of the famous Julliard School of Music. While sitting under the tutelage and instruction of Todd Stoll, Eric Reed, and famed jazz trumpeter and educator Wynton Marsalis, Diehl made a name for himself when Marsalis chose him to tour with his traveling Septet.

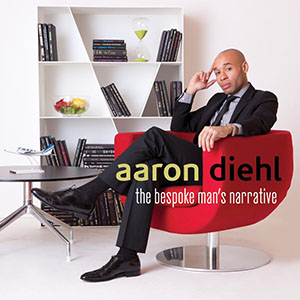

Diehl is the recipient of multiple awards for his outstanding musical talent such as the Cole Porter Fellow in Jazz of the American Pianist Association, and the Lincoln Center’s Martin E. Segal Award. After leaving the Marsalis Septet, Diehl started his own trio featuring David Wong, Warren Wolf, and Rodney Green. Diehl’s recent pairing with famed young jazz vocalist Cécile Salvant is winning fans of all different demographics worldwide. He has released four LPs and The Bespoke Man’s Narrative is his latest offering to the jazz loving public.

Aaron Diehl’s new album – “The Bespoke Man’s Narrative” (EPK) from PopovMedia on Vimeo.

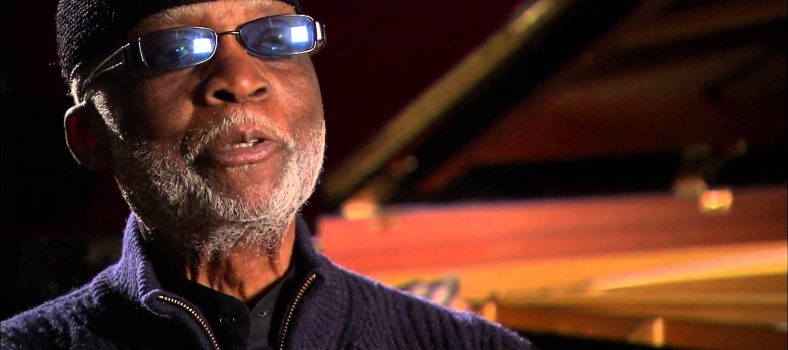

iRockJazz spoke with Aaron Diehl who now lives in Manhattan and when he is not touring still plays piano for the St. Joseph Holy Family Church in Harlem.

iRJ: How did you get your start in the industry?

AD: When I was in high school Wynton came and conducted a master class in Columbus Ohio my hometown. I was in a band called the Columbus Youth Orchestra, which was a regional band for high school students who were interested in playing jazz. Todd Stoll who was a band director knew Wynton, so he had him come and conduct this master class it was gracious for him to work with us. That was the start of our relationship; Wynton gave me his number and said ‘You seem like a serious young guy keep in touch with me’. So we kept corresponding for a few years, Wynton called one day in the Spring of 2003, when I was just about to graduate high school he said ‘Hey I want you to come out on the road with me and my group and get your feet wet and see how it goes’. I went out on the road with him for about two months we traveled to Europe yeah it was incredible.

iRJ: How did you feel being recognized for your talent by a famous jazz icon like Wynton Marsalis?

AD: I think for the most part I really didn’t know what I was doing I did the best that I could to learn the material he gave me. I didn’t have much experience at all playing with a lot of seasoned professionals on a national level. I had some experience playing with local musicians who were good, and I was fortunate enough to have a certain caliber of good musicians who were elders in my hometown, but even with that, I never had the experience that was required to play with someone like Wynton and his Septet because those guys played together for such a long time. I think Wynton did it primarily because he knew that I was passionate and serious and wanted me to see what it was like being out on the road playing with guys of that level, such as Herlin Riley, Reginald Veal, Wes Anderson Victor Goins, and Ron Westray and so I thought it was a very valuable lesson. I sometimes will listen to recordings of myself playing from that period just to see how far I’ve come along, and also realize how far I still have to go.

iRJ: Was it a difficult transition leaving your local surroundings to tour on a national level?

AD: Absolutely! You’re not only talking about performing the music, you’re also talking about traveling, a lot of overnighters, riding the busses, there was a grueling travel schedule, also being with guys who are a lot older then you are, not having any body in your age group, there are all kinds of challenges to navigate but I think at the end of the day doing that made me a stronger person.

iRJ: What was the hardest part of that transition?

AD: What was most reveling is that no matter how much you learn from playing the record or a recording, it could never substitute for the real thing, I was studying all of Wynton’s recordings from the 90s when he was playing with the Septet. Over the years the music had developed with the ensemble over a course of ten years so they worked out new ways of approaching the material, and while still working with the original recording. It was very intimidating at some point, and I could be discouraged at times, but fortunately the guys were encouraging they understood they said ‘You’re young and you still have a lot to learn.’ During that point of time I really didn’t understand the value, or knew how to listen to people while I was playing, and that’s a skill that constantly needs learning and refining. Being that young it’s hard to understand how to really listen and be aware of your surroundings before you’re a star.

iRJ: Now that you have started forming your own sound, your own music and are building your own separate career what was the transition like leaving the fold of a Wynton?

AD: Well you know it was a fairly smooth transition, in the sense that the guys with whom I work now are just a little bit older than me, but we are all within the same peer group. I’ve been working with David Wong since about 2005 or 2006 he was in one of my small ensemble classes at Julliard. We played together my first year while he was studying classical bass, he is an amazing classical bassist as well as a jazz bassist. These guys with whom I formed and worked with on a regular basis enabled me to develop with them over a few years. I think that’s very important for young artists. Its also important to play with older guys, developing your voice with your peer group and having that kind of camaraderie and sense of dedication to each other I think that is very important.

iRJ: How did you start working with Cécile Salvant?

AD: Cécile and I we connected through Ed Arrendell who is Cécile’s manager and also Wynton Marsalis’ manager. Wynton recommended me, and my trio with Paul Sikivie and Lawrence Leathers. Wynton had us play a few times with him and he recommended us for Cécile. After meeting we started off talking to see if it would be a good fit or good arrangement, we had a first gig last April at the Kennedy Center. We thought the pairing up would be something that would work so we have been playing together about a year or so. She is so spectacular; she has a great command of the jazz language and at such a young age. We have good chemistry – I think that is so important when working in an ensemble, we love working together and hanging out we love each other’s company so it’s great to grow with somebody like that.

iRJ: The musicians who play the Kennedy Center are considered the top echelon of classic jazz performers and artists, do you feel that playing other genres of music or types of jazz is confining or pigeonholes you to what people’s perception of you and your abilities?

AD: I find it important just to master a language and that’s the language of jazz. I used to play classical music. I don’t do it anymore because I don’t have the time to master or refine that style of playing. My own opinion if you’re going to be a jazz musician you have to understand the language of jazz. You should learn everything from Jelly Roll Morton to Herbie Hancock and beyond as much as you can acquire. As musicians we are always developing, we never stop learning. Hank Jones told me that and I saw him do it before he passed away. He was practicing at 90 years old. It is about just practicing and mastering a language and jazz is a language just like funk is a language. Guys who play that music constantly are going to master the style.

iRJ: What was your inspiration for your latest album?

iRJ: What was your inspiration for your latest album?

AD: The Bespoke Man’s Narrative I came up with the title because I thought about all the guys I’ve been working with for the last couple of years; Warren Wolf, David Wong, Rodney Green and actually Rodney came up with the idea when we were playing music of a modern jazz quartet for some projects. We should start thinking of ideas how we could use or learn from some of the tools that John Lewis used with that group MJQ (Modern Jazz Quartet) and maybe apply our own sound and our own concept through our own composition and that’s how I came up with the title. I’ve been working with those guys for a couple years and we thought it would be nice to record having the opportunity through the American Pianist Association and receiving the fellowship and recording original music and standards on this album and that’s The Bespoke Man’s Narrative.

iRJ: Do you feel a certain level of responsibility after being tapped on the shoulder by Wynton and now do you feel like a baton is being passed on to you and others to carry on the history.

AD: My dad told me when I was a kid ‘Whom much is given much is expected’. The opportunities I’ve had, the lessons I’ve learned from other musicians allowed me to realize the importance of carrying this music along for another generation of musicians who will come behind me. I think it’s important to continue this legacy, it is such a rich tradition that we have, and we have to utilize all the resources at our disposal – elder musicians our own peers, and also those musicians we will hear about later. A lot of younger guys coming out right now Emmet Cohen, Chris Pattishall, George DeLancey – I think it’s important to build a community of musician and listeners alike to be able to enjoy the wealth of music that will continue to be made there is certainly a responsibility on everyone involved not just a small few.

iRJ: Where do you see yourself in the next ten years and how will people view your music and your legacy?

AD: That’s a really loaded question at this point of time. For me continuing a trajectory where I am developing with artists of all generations and to have a role in education, and to spread the good news is what the music is all about. At the end of the day for me, it’s about possessing excellent musicianship musicality and being able to share that with others and being able to participate with other musicians who share those same goals, who are continuously focused on playing jazz at its highest level.

By K. Gerard Thomas