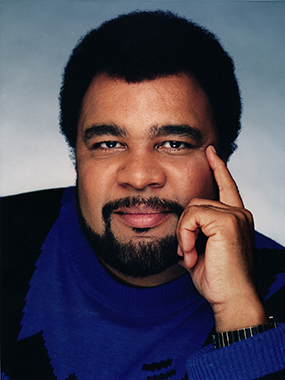

George Duke is a Grammy Award-winning musician whose career has spanned over forty-five years. During this time, Duke has traversed a multitude of genres as both a performer and as a producer, working with artists ranging from Frank Zappa to Julian “Cannonball” Adderley. Duke has also made his mark as a solo artist, releasing 38 albums to date. His latest record, Dream Weaver, is slated for release in July.

When working in jazz, the idea of “good music” is as pervasive as modal scales. The form serves as a cultural barometer, situating the listening public. To many, jazz is at the epicenter of refined taste; America’s classical music, if you will. And there is some truth to that statement. Jazz is one of the earliest constructs of an authentically American culture. However, this notion is problematized when an understood historical contextualization diverges into outright elitism.

Once upon a time, jazz was the product of a countercultural revolution akin to its progeny, hip-hop. Fifty-five years after the closing of the Savoy Ballroom, jazz is now seen as “art music,” meant to be displayed in the archaic confines of a chamber hall. And somewhere in between, an artisan class of freethinking radicals emerged, eschewing any illusions of grandeur. George Duke was amongst them.

His is a story of acceptance. While many would say that he pushed musical boundaries, his career is a testament to the fact that these limitations do not exist in the first place.

iRockJazz sat down with George Duke to talk about his evolution in both playing and perceiving the music of his mind.

iRJ: You hear about musicians jumping directly into their careers, but you have a strong musical education background, earning a bachelor’s in trombone and composition. What were some of the benefits in receiving that formal education?

GD: It’s the background no doubt. I geared my college classes towards what I thought I wanted to do. It turned out to be arranging and orchestration. I wanted to learn how to write and arrange. It set the stage for everything I’ve done since. The trombone thing was just a matter of a scholarship. I knew there were few, if any, trombone majors there. I mean I wanted to get the money [laughs] we were not rich. It was very, very heavy for my mom to send me to college. So that helped out.

iRJ: Primarily, you’re known as a jazz artist, but over the course of your career, you’ve crossed over to funk, rock, pop, and various other genres. What led you to work with these other styles of music?

GD: I started out as a straight-laced jazz player. I had been working with Al Jarreau at this little club while I was in college, both of us honing our craft. Eventually, I found out a guy named Jean-Luc Ponty was coming to town and I kind of got extroverted with my talent and said, ‘I’m the only guy that can play with him’, and eventually he gave me a shot. By working with him in the Los Angeles area, I was seen by Frank Zappa, Cannonball Adderley, Quincy Jones, and on and on. So, I began to get a lot of work based on my work with Jean-Luc. Now working with Frank Zappa and Cannonball Adderley, they both got me to look at other forms of music. They got me to open up my mind to the palette available and not be so narrow musically. At the time, I was a bit of musical snob. Frank said to me, ‘Look, you’re a musical elitist. You need to change that especially if you’re going to be in this band, because that’s not what we’re about’.

GD: I started out as a straight-laced jazz player. I had been working with Al Jarreau at this little club while I was in college, both of us honing our craft. Eventually, I found out a guy named Jean-Luc Ponty was coming to town and I kind of got extroverted with my talent and said, ‘I’m the only guy that can play with him’, and eventually he gave me a shot. By working with him in the Los Angeles area, I was seen by Frank Zappa, Cannonball Adderley, Quincy Jones, and on and on. So, I began to get a lot of work based on my work with Jean-Luc. Now working with Frank Zappa and Cannonball Adderley, they both got me to look at other forms of music. They got me to open up my mind to the palette available and not be so narrow musically. At the time, I was a bit of musical snob. Frank said to me, ‘Look, you’re a musical elitist. You need to change that especially if you’re going to be in this band, because that’s not what we’re about’.

iRJ: What did you take from your relationship with Miles Davis?

GD: How much time you got? You can learn something just from listening to him, but once I met him, I learned how much music meant to him. That was his life. He was the music. He loved the change. He loved to be incorporative. Miles wanted to be inclusive not exclusive. Jazz was a really broad term for him and it became a really broad term for me. I learned that from him. You need to incorporate other things into what you do, but stick true to who you are, no matter what. No matter what Miles did, he still sounded like Miles. That’s what I try to do. No matter what style I do or what I play, I’m still in there. Miles taught me to be daring. That’s what it is.

iRJ: You’ve mentioned Cannonball Adderley and Frank Zappa. It would seem as if you’ve worked with pretty much everyone. Could you name someone that you’d like to work with, but haven’t had the opportunity?

GD: There are a few people that would be kind of interesting. It could be an unknown artist, someone that wants to push the envelope. I’m not really interested in doing something with another artist that’s extremely conservative. I think it’d be interesting for me to get together and do a project with Robert Glasper. He, as a young artist, has an interesting idea about what music could be, combining that with what I believe about music, I think it could be kind of interesting. I’ve always wanted to work with Jill [Scott]. I did play on her record, but we haven’t actually gotten into the studio together and worked on something. There are a few others like that. Christian Scott—great trumpet player, young guy from New Orleans. There are a few younger artists I really wouldn’t mind getting together and working with.

iRJ: Speaking of Robert Glasper and Christian Scott, two modern jazz artists that have pushed the envelope, how do you feel about modern jazz and what these artists are doing to the form?

GD: Whether I like it or not, I applaud these guys for pushing the envelope. It’s the exact same thing I was doing when I was their age. When Herbie Hancock, me, Stanley Clarke, and Patrice Rushen began putting funk rhythms into jazz, I was called out in all the papers. ‘He used to be a good piano player, but he’ll never last’. [laughs] Look man, I love the stuff they play at Carnegie Hall, the lofty intellectual kind of stuff, but I’m from the church. I love music from the soil. That’s where jazz started. It was dance music. So I don’t want to lose that in my music. For jazz to stay vital and alive, it must incorporate the sounds of the day and the artist should then do their thing around it. And that’s what I chose to do—what Miles did, what Frank did, what Quincy did.

George Duke and Stanley Clarke photo by Louis Byrd III

George Duke and Stanley Clarke photo by Louis Byrd III

iRJ: Many modern artists have embraced your music from Common to Daft Punk. What is it like hearing your music sampled by music makers today’s generation?

GD: I think it’s great. I love Common. As a matter of fact, he mentioned to me that he wanted to record the song. I thought, ‘That’ll never happen’. I just didn’t see it. And when he eventually did it I said, ‘No kidding. What the heck did he do with that song’? It was cool, because I would have never thought of that. I put out this thing about a year ago called Soul Treasures. I went into the studio and played 8 hours a day for 3 days—every possible lick I could think of on piano, Fender Rhodes, clavinet and Wurlitzer. If they buy the CD, they can use it royalty free to make new material. I’m kind of interested to see what these young guys do with this stuff….as long as they pay me. Hello! [laughs]

iRJ: You’ve done so much in your career. What motivates you to continue performing and making music?

GD: Love. As quiet as it’s kept, I do this for nothing. This was something I was led to do. When my mom took me to see Duke Ellington when I was four and a half, I knew immediately that I wanted to do that. Back then, the whole idea of what he was doing was something I was interested in and that’s continued to this day. I’m just as excited about going on stage now, if not more, than I was at 20 years old. I’m always looking for that other thing. David Sanborn had this thing where he said that inspiration is like a bird flying around out there and every now and then it will land on your head. So, you come up with something that’s absolutely amazing, but then you try and keep it there, but the bird always flies away and you just keep trying to get back to that point. Striving for that elusive melody, the one that not only connects to you, but God and everyone in the audience, that’s an amazing thing, man. Having someone come up to you and say ‘That song you wrote thirty years ago got me through college’, that’s what keeps me going.

Progressive thought has a way of transcending generations. And this is why the music of George Duke has stood the test of time. His influence extends far beyond the expansive realm of jazz, making stops at funk, rock, pop, and now into the ever-changing world of hip-hop. These are the new trendsetters. They create with his work—the maintenance of a free flowing tradition. While we praise those modern artists who attempt to redefine sound, we must first look back and salute the ones who did it first. George Duke is the evolution of music.

By Paul Pennington