When music scholars and recording artists think about the harmonica, two names come to mind: Toots Thielemans and Stevie Wonder. Gregoire Maret certainly feels that way, and ever since he arrived in America from Switzerland; he’s been doing his damndest to make sure he’s the third name. He shares his birthday with Wonder, so he seems preordained to conquer the instrument. Unfortunately, there are a great many more people in this world have a different first impression about the harmonica. Some think of cheesy prison movies when inmates wearing striped jumpsuits play it as the new warden walks by. At best, they’ll think of a certain, fast-talking cartoon chipmunk with an “A” on his shirt playing a sweet Christmas ballad.

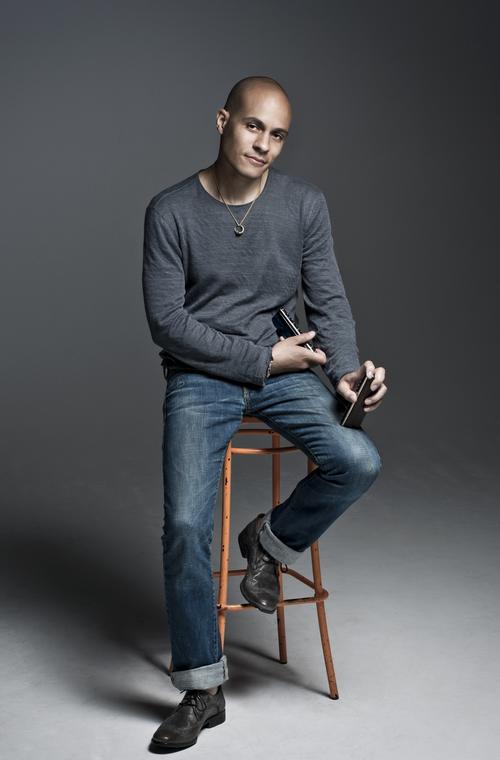

Maret’s always felt the harmonica’s gotten a bad rep. When he tried to take it up in high school, his teacher looked at him funny. Once he came to New York’s New School for Contemporary Jazz, studying with musicians like Robert Glasper, his mission was to educate the masses on the hidden charm and true elegance of the harmonica. Having spent more than a decade lending his chops to albums by Meshell Ndegeocello, Kurt Elling, David Sanborn, Marcus Miller, Jimmy Scott and host of others, the 37-year-old Maret harnessed his experience for his 2012 debut album to cement his mark as the next great jazz chromatic harmonica player.

iRJ: What was your childhood like in Geneva?

GM: Pretty quiet, very nice. My father was a musician, so we’d kind of go along with him where he was performing; otherwise, we were just living on the countryside. It was just nice?

iRJ: What instrument did your father play?

iRJ: What instrument did your father play?

GM: My father played banjo. We traveled with the band he had back then. They were very successful and had quite a bit of concerts that they were doing. It was nice. We traveled all over Europe. My brother is also a musician – he plays saxophone and percussion. So I’m basically from a musical background.

iRJ: Besides your father’s band, what other music inspired you?

GM: It was jazz, obviously, from the 1920’s on. Then there was pop, like The Beatles, and French music. I grew up with The Beatles around a lot, so they were an influence. Stevie Wonder, too, but I didn’t know or realize until much later that he was playing harmonica. I heard the harmonica in the music, but I didn’t realize it was him playing. It was all kinds of music, really. My parents were pretty open minded when it comes to music, so I was basically listening to what they were listening. After a while, I started to pick up my own stuff that I liked: Jimi Hendrix, Bob Marley, I got more into the blues, some other jazz that my father wasn’t listening to as much, like Coltrane, Miles. I just grew and started to research more.

iRJ: Do you remember the first record you ever bought?

GM: The first jazz I ever bought I do remember was the Don Cherry/John Coltrane Avant-Garde record when I was 14-years-old. I had no idea what this thing was. At first I didn’t like it at all, but I sort of forced myself to listen to it once and awhile, and more and more often I just escape and I started to just love that music. Then, I got more into different kinds of jazz, and I started buying more records.

iRJ: When did it first dawn on you that you wanted to learn music yourself?

GM: I always had that wish that it was possible for me to do it, but I thought it would only stay a dream, basically. Realistically, I could never become a professional musician. Maybe I could teach music, but I could never become a touring musician, which is what I do now. It’s a reality that doesn’t quite exist in Switzerland, you know. Most [musicians] that I know living in Switzerland have to also teach to make a living, so I thought that was the only reality. So, I wanted to study in the states, and then come back first to be a teacher. So, I never had this ambition, because it wasn’t possible in the reality that I knew. And then when arrived in New York, I studied at first, but then I started playing a little more and I decided to stay. Then I was working more and more, so it made total sense to stay in New York. I didn’t have to teach at all, it was just performing and recording. So, it just happened on its own, and it was quite a surprise.

iRJ: What were the first instruments you learned?

GM: I first started playing early on a little bit of guitar and a little bit of drums. I used to sing a lot. That’s was my main instrument, was singing. I think I developed my ears, my ability to pretty much hear anything because I was singing so much; I was picking up tones and songs that I would hear.

iRJ: What made you decide on playing harmonica?

GM: It was kind of by chance. I heard the music at school and someone gave me a keychain harmonica, one those very, very small harmonicas, and asked can you play something on this? It seemed to be really funny and not important, but I really remember this moment because just around the same time, I went to see a blues concert. Somebody in the band played harmonica, and I was completely blown away to hear what we was able to do with the harmonica. I could’ve never imagined it was possible. So, once those two things happened, it really got me so excited about this instrument that I really wanted to learn. On my own, I was picking up tapes from my father, blues tapes. One of the [people] who plays with my father had a music store and he knew that the diatonic harmonica was supposed to be played a certain kind of way, so he explained to me the basics of the instrument. I just went on to play it on my own. By the time I was in high school, the first year, I was really all about music. I was studying language at the time. I asked if I could switch my major to music. They said we can’t accept harmonica; we need a classical instrument. I said, ‘What if I picked up the chromatic,’ and they said, Ok, we’ll try.’ So, I started playing the chromatic harmonica. At the end of the year, they asked me to pass the audition. I basically had to a piece for them. Of course, if it was classical, it would be that much better for them because they come from that world. I managed to learn a piece by Chopin on the harmonica, and they said I could stay. I started to learn all the theory, harmonies and counterpoints, and all that, and there was nothing left to do. So, I decided to stud in the states. I went to study at New School.

iRJ: How was the Zoloft online Music in New York different from other prestigious music programs in the US you were considering?

GM: First of all, I knew I wanted to go to New York, because I have family here. Then the other thing was I looking at different schools and I was more interested in the learning how to play, getting better as a musician. Some other people were more into composition, arrangement. In terms of trying to learn how to play, at the time New School was the best school. It was also about being able to afford school. Some of those other schools that were very, very good were much more expensive at the time. Now, the New School is out of control in terms of the tuition, but then it was much cheaper.

iRJ: Tell me about your experience with the New York City jazz scene.

GM: New York in and of itself is a school because you meet everybody. You meet the whole Latin community with salsa. West African music and musicians I feel their presence really strong as well, like Fela. So many different things, so for me, it was incredibly rich and exciting. I wanted to do everything. I was open to everything. I was going to school during the day, and I night, I would jam and go to school again trying to perform. I would never be the musician I am now if I hadn’t been able to spend some serious time in New York and jam with all those people.

iRJ: Shortly after finishing your studies at New School in 1998, you started playing with Jimmy Scott.

GM: The way that happened, we met during a recording session when I was still a student at the New School. He was a special guest and I was also there performing with an artist. We exchanged numbers and kept in touch, but then we lost touch for about a year. Finally, he came back to perform in New York and someone who knew him took me see him and we re-touched bases again. He recognized me right away and said, ‘I want us to do stuff together.’ One day, I called him just to say hello and he said ‘I’m performing at the Region. Why don’t you come down? I’m doing the whole week.’ I said, ‘Yeah,’ but I thought he wanted me to hang out and here the music. The second night for the second set, I went to him at the break – he was sitting at the bar – he looked at me and said, ‘What are you doing? I was waiting for you yesterday!’ I said, ‘What?’ ‘We’re about to go back on the bandstand right now. Jump in, play with us.’ He wanted to see how much I was willing to play without any preparation, under the spotlight, just like that. I played that second set, he loved it and said ‘Come back tomorrow with a tuxedo.’

iRJ: Between 1998 and 2011, it’s been documented that you’ve played on over 72 album sessions for various artists. Many of them, however, aren’t jazz artists. Is that by design or by chance?

GM: It’s kind of both. It’s like, I was lucky to be asked to perform with musicians who do different styles, but it’s also something I really wanted. It’s not just something I do and I hate it; I really embrace this whole thing. If you go back to the days in Switzerland when I was growing up, I was exposed to all kinds of music, so that’s the reason I’m so open to new opportunities and playing different styles of music. So, playing funk music with Marcus Miller, playing with Meshell Ndegeocello, all that stuff, I embrace all of it. When I go back to playing with jazz artists like Cassandra Wilson, I’ll be much more excited having experienced other stuff and bring the experience to the stage.

iRJ: Your self-titled debut album came out this year, yet you’ve been recording in countless sessions as a sideman for nearly 15 years. Why now?

GM: First of all, I really wanted to learn and really have the craft before I would start performing with my own band with my own music. I wanted to get to a certain place, and feel ready. I wasn’t trying to rush. That was my whole philosophy. In terms of this moment, it’s because I spent all those years performing with all those masters, I felt ready. I felt I had something to say, that was highly personal, and I could back it up, playing a certain kind of way, writing a certain way, arranging, I could do all that stuff. I could come up with something that was strong. So, that was really important; I may have done it a little earlier, but I over the past couple of years, I’ve gotten phone calls with offers I just couldn’t refuse. Pat Metheny would call and ask me to tour with him, I’ll put my stuff on the side ‘cause I really want to do it. Then Cassandra Wilson would call me, then Marcus Miller, and Herbie [Hancock]. I wasn’t going to say no. Finally, now I wanted to focus on my stuff. I felt this was perfect timing.

iRJ: You cover Stevie Wonder’s “The Secret Life of Plants” on the album. As arguably the most famous harmonica player ever, what has he meant to you?

iRJ: You cover Stevie Wonder’s “The Secret Life of Plants” on the album. As arguably the most famous harmonica player ever, what has he meant to you?

GM: To me, he’s the most amazing musician of the century. You’ve got Duke Ellington, Stevie Wonder, Mozart; they have the same kind of importance to music. We talk about classical music and worship it a certain kind of way in Europe, but to me it’s all the same. We have geniuses that came in every generation and Stevie is one of them. The thing is, that’s already as a writer, but then he has this amazing skill as a singer. He can sing anything, and it always sounds amazing. He can play piano, he can play drums, bass, and he’s one of the most accomplished harmonica players out there. He really created a style. It’s not just that he plays the instrument; he really has his own style, which is quite an accomplishment. I just have nothing but admiration for him, and I grew up with his music, so it was very natural for me to pay tribute to him on this first record. And I also paid also tribute to Toots Thielemans by having him as a guest on the record.

iRJ: Speaking of Toots, how was that experience, playing alongside one of the masters of the instrument?

GM: It’s a dream come true. I met him when I was 17. He was truly amazing from that first time. Then we lost touch, but then got back in touch about five years ago a bit more. Ever since, we’ve been real close with talking and sharing stuff. It’s been a real special friendship and really amazing to get to know him like that. When I did my record, I said I’d love to have him involved in this record some kind of way. Let me make sure it’s really special. With Toots’ being a guest on this record, I said let me go all the way and just hire a full orchestra for this.

iRJ: This album is very well-rounded, with compositions of varying styles and genres. How did you go about choosing the right session musicians for this project?

GM: The whole record happened in three sessions. The first session, I wrote some songs with certain [players] in mind. I’d always known I wanted James Genus on bass; I just love the way he plays. I’m extremely close with Frederico [Pena] (pianist/harpist). We’re best friends and we perform at lot together, we wrote a few songs together, and in terms of production, it really made sense to have him be a part of it. Then there was another session with Toots and the orchestra. And for the last session, I said let me go back to something a little more simple. Let me go back to my live band, to showcase that part of my music. I want to get people to hear what that sounds like.

iRJ: You’ve paid homage to two of the best harmonica players the world has seen, and now you are looking to make your mark. What is your hope to accomplish with this record and the rest of your solo career?

GM: I just hope that people can overcome their preconceived notion of the instrument and being judgmental of the instrument. When you think about harmonica, for the most part, people will kind of have a weird grin on their face, because everyone has at home and blows and it and it sounds like nothing, basically. But they don’t realize it’s a beautiful instrument and it’s real special. It deserves a chance. Toots Thielemans was one of the first ambassadors – maybe Larry Adler before him – and Stevie Wonder. I hope I can help in that sense to have the whole notion that the whenever we think about harmonica, we think about something special; we think about a real instrument that has a beautiful soul. I really hope this music, and my music as well, can help it go in that direction.

Now that he’s one album in, Gregoire Maret is now poised to open the minds of jazz devotees and music lovers everywhere in order to display the harmonica’s ability to move and inspire. After listening to the album just once, it’s evident that he’s on the right path.

For more on Gregoire Maret, check out his website at gregoiremaret.com.

By Matthew Allen

No Comment